Art World

11 Everyday Objects Transformed Into Extraordinary Works of Art

From car tires and duct tape to pencils and couscous, ordinary objects are both clay and canvas in the hands of these singular artists.

From car tires and duct tape to pencils and couscous, ordinary objects are both clay and canvas in the hands of these singular artists.

Artnet News in Partnership With Cartier

Since the very first artists painted cave walls with mineral pigments and clay, humans have been making art with the humblest of materials. The practitioners highlighted here are the contemporary counterparts of those first artists, using the most ordinary and mundane matter to create artworks that often not only provide ravishing visual experiences, but also contain far-reaching ideas. The almost magical transformation that occurs in the mass accumulation of these objects is part of a long tradition of artists as tricksters, employing optical sleights of hand. The materials chosen by these artists are all objects that serve a specific purpose that the artist abandons, choosing to elevate the mundane to the realm of fine art, and dissolve the boundaries between “high” and “low” forms of culture.

1. Bluffs (2006), Tara Donovan

In this piece, American artist Tara Donovan created a sculpture made entirely from plastic buttons and glue. Through the simple act of stacking, the effect is that a stalagmite made of crystals has simply erupted from the gallery floor. Donovan is well known for her large-scale sculptures that use store-bought materials like toothpicks, drinking straws, plastic cups, and Scotch tape to create organic forms. Her work has earned many accolades, such as the Calder Prize in 2005 and the MacArthur Foundation “genius” award in 2008, as well as solo exhibitions at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the UCLA Hammer Museum. To build her sought-after sculptures, Donovan repeatedly deploys a single material until it becomes a form resembling fractals or a beehive.

2. Untitled (2012), Wim Delvoye

Wim Delvoye was once considered the enfant terrible of the contemporary art world—thanks in large part to his use of uncommon materials, and his unabashed derision for the mores of the art establishment. Delvoy’s artworks straddle conventions of vulgarity, beauty, and taste; he subverts objects’ intended use to reveal a complex beauty that is often jarring. In his “Pneu” series, the artist hand-carves rubber car tires with motifs whose curlicued florals and sinuous vines recall Art Nouveau decoration. The anachronistic ornamentation that Delvoye applies to the tires was underscored further when they were displayed in the Louvre as part of a 2012 exhibition.

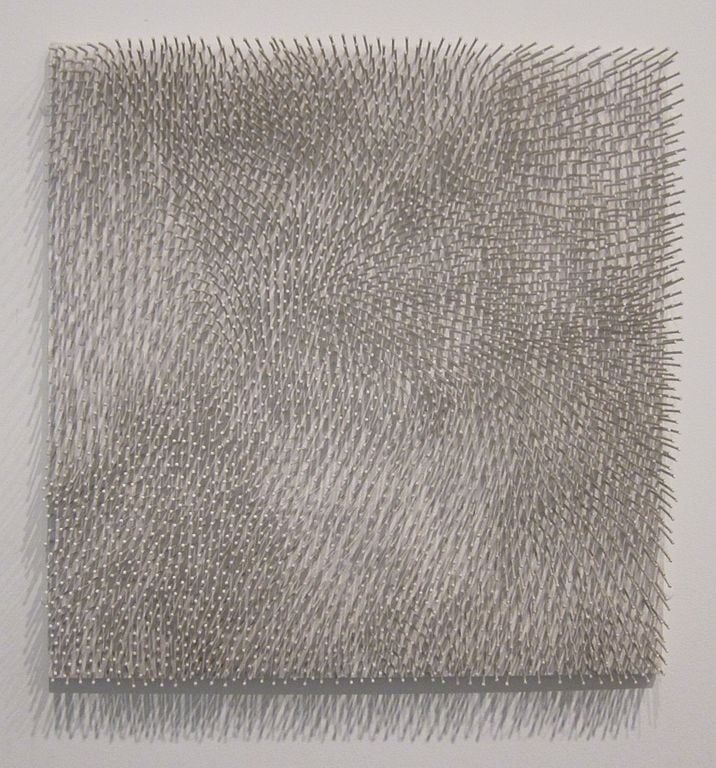

Günther Uecker, White Field (1964). Photo courtesy Tate Modern.

3. White Field (1964), Günther Uecker

German artist, set designer, and ZERO Group member Günther Uecker studies light and optics to make mesmerizing works of abstract art—and all he needs in his studio is a hammer and some nails. In pieces like White Field (1964), he takes hundreds of nails and creates atmospheric images full of motion and tension. His approach draws partly on his interest in systems of thought, like Buddhism and Taoism, that he sees as prizing simplicity and purity. Uecker’s meditative works have earned spots in major collections, including the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

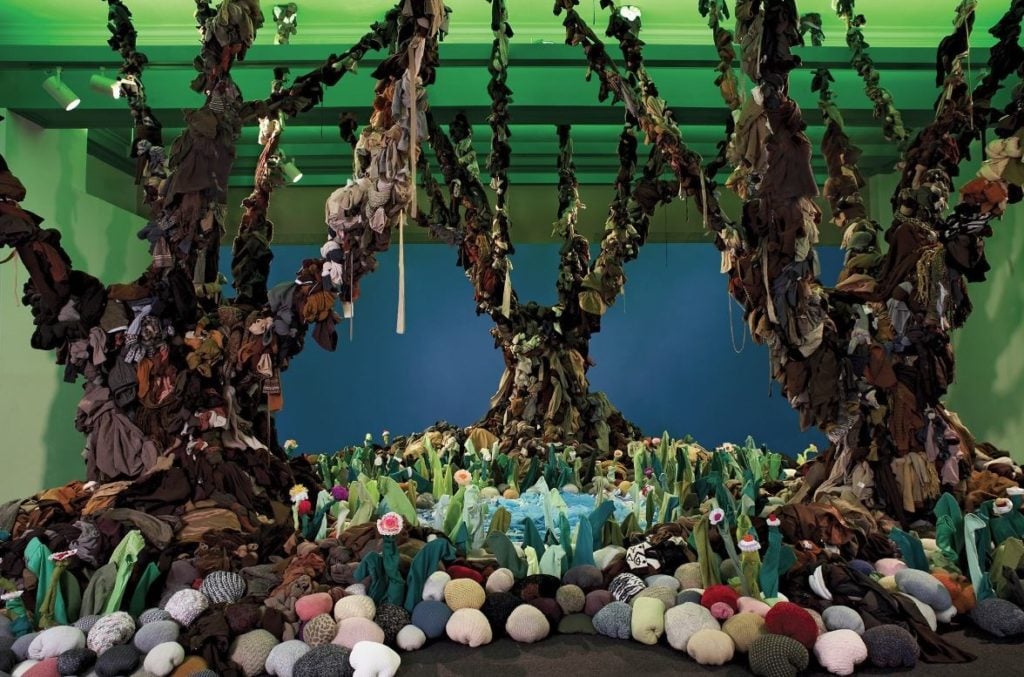

Guerra de la Paz, Oasis (2016). Site-specific installation at Chicago Cultural Center.

4. Oasis (2016), Guerra de la Paz

Collaborating since 1996, the duo of Cuban-born artists Alain Guerra and Neraldo de la Paz began by making installations out of ingredients salvaged from trash cans of Miami companies that ship second-hand clothes. Many of their most iconic works transform used garments; the one illustrated here melds them together into a magic garden, complete with trees towering over adorable flowers. The artists have been granted shows at venues like the Saatchi Gallery, London; the Kuruyama Museum of Art, Oyama City, Japan; Daneyal Mahmood Gallery in New York; the Museum of Contemporary Art Caracas; and the Hyde Park Art Center, in Chicago.

5. Geo Eye (Victoria Peak) (2012), Takahiro Iwasaki

The meticulous carvings of Geo Eye (Victoria Peak) transforms household duct tape into a canvas for Iwasaki to carve an intricate topography.Born in Hiroshima in 1975, Iwasaki has been described as a quintessentially Japanese artist, favoring slow, often laborious processes that result in detailed constructions. He will represent Japan in the national pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, where his craftsmanship will be set on the world’s stage.

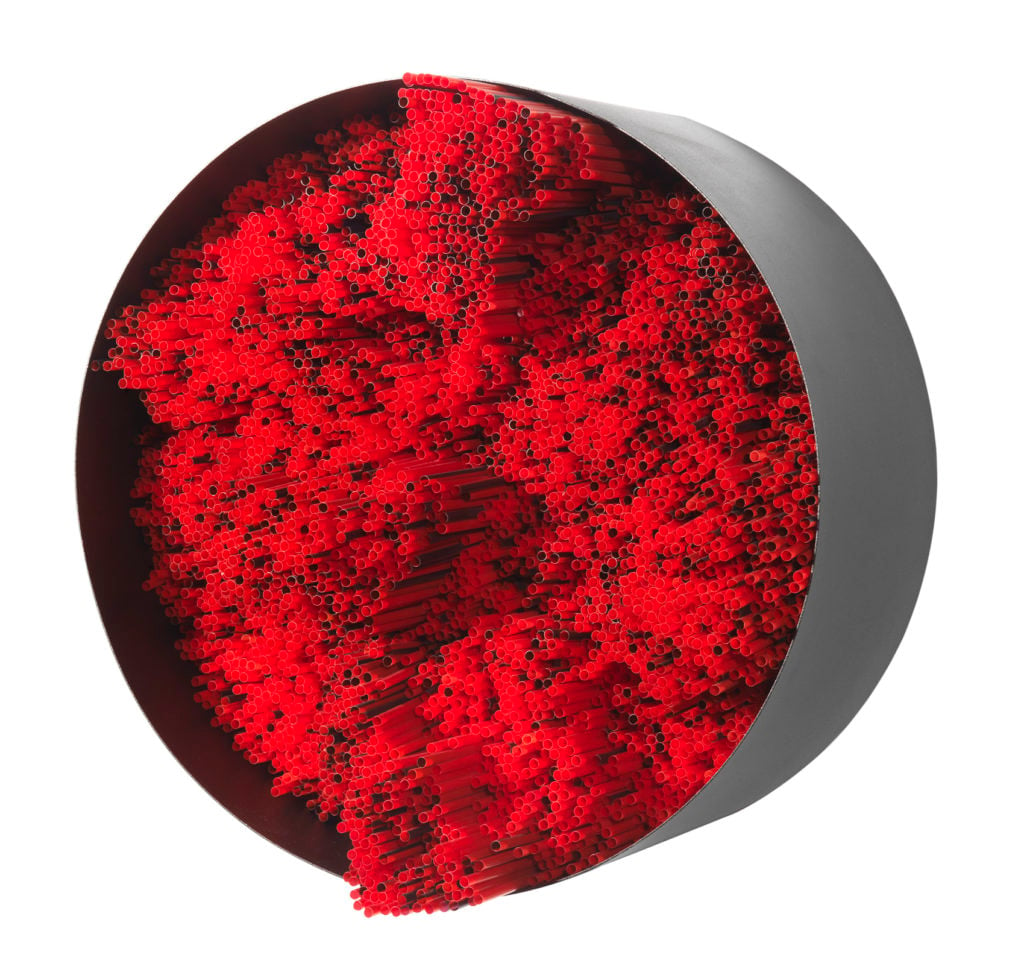

Francesca Pasquali, Red Straws, 2015. Photo courtesy Leila Heller Gallery.

6. Red Straws (2015), Francesca Pasquali

Bologna-based artist Francesca Pasquali takes countless colorful plastic straws, balloons, and rubber bands and fashions them into colorful works of art in which synthetic materials echo organic shapes. In sculptures like Red Straws, Pasquali harmonizes a myriad of the simple plastic tubes to build an undulating surface that recalls forms in nature. Her straw sculptures are in the Ghisla Art Collection, Locarno; the Museo Diocesano, Brescia; and the MAR Museo d’Arte della Città, Ravenna. Pasquali was a finalist for the 2015 Cairo Prize, and has shown in many of the art capitals of the world, including London, New York, Berlin, Paris, and Venice.

El Anatsui, City Plot (2010). Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery.

7. City Plot (2015), El Anatsui

As one of the best-known artists of the late 20th century, El Anatsui has set the bar high for the poetic use of mundane materials. His work touches on consumption, the environment, and the history of colonialism. Born in Ghana, El Anatsui sources scraps of metal from local recycling stations, weaving together bottle caps and copper wire in works like City Plot (2010) to create glistening and colorful forms that hang on the wall like folded tapestries. El Anatsui has earned great acclaim, including the Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 2015 Venice Biennale, and his sculptures are housed in many museums, not least the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Federico Uribe I Am Not Bambi (2016) Image: Courtesy of the artist and Adelson Galleries.

8. I Am Not Bambi (2016), Federico Uribe

Born in Bogota, Colombia, Federico Uribe began his career as a painter in his native South America before moving to New York, and eventually Miami, where he is currently based. After abandoning painting, Uribe began to collect knickknacks and organize them by color and shape—allowing him to see the potential unity that could arise from serial repetition. Uribe’s sculptures are made of colored pencils, coins, screws, plastic cutlery, and clothes-pins. In 2015, he mounted an exhibition titled “We Are At Peace,” filled with whimsical animal sculptures made of thousands of bullet shells, in an attempt to bring awareness to gun violence, and to turn an object associated with horror and death, into one of beauty.

9. Implements 3 (2011), Jessica Drenk

The “Implements” series are created by gluing thousands of pencils together as a large mass, which Drenk then shapes using an electric sander to form geode-like vessels. Of the series, the artist says “each piece exhibits a contrast between man-made geometry on the inside, and an outside evocation of natural shapes and textures.” As a result, on the outside, we see the stretched and magnified core, bleeding together into a mass of wood and lead, sanded to a smooth finish—that houses a crater of unsharpened no. 2 pencils on the inside, nestled together in a honeycomb pattern.

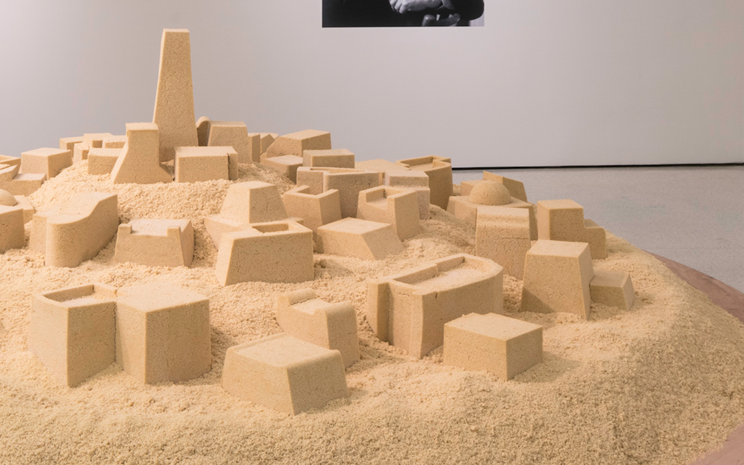

Kader Attia, Untitled (Ghardaïa) (2009). Image courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, Galerie Nagel & Draxler

10. Untitled (Ghardaïa) (2009), Kader Attia

In the “Living Cities” room of the Tate Modern in London, Kader Attia has constructed a scale model of the ancient city Ghardaïa, in Algeria’s M’zab Valley—made entirely of couscous. Resembling a giant sand-castle, the pearly grains are packed densely to form geometric shapes to approximate the architecture of the city. The work is a commentary on the often troubled relationship between Eastern and Western cultures—and by using a food product that is a staple of North Africa to approximate architecture that owes much influence to European architecture, he is drawing our attention to the inherent tension. Attia has said “architecture is an archive, and like any other archive it is ‘authoritarian’…but this authority has a vulnerability that art can reveal,” and so his use of an organic material, meant to crumble and decompose, Attia is posing questions on the nature of authority itself.

Nick Cave, “Until” (2016), installation view, MASS MoCA. Photo by James Prinz, courtesy of MASS MoCA.

11. Until (2016), Nick Cave

Nick Cave is largely known for his interactive “Soundsuits,” wearable sculptures that are comprised of colorful second-hand objects and organic materials. Many of the suits were conceived of in the wake of traumatic societal events—the first iteration, made in 1992, was Cave’s response to the Rodney King beating—and by using the detritus of contemporary life, the artist is preserving a particular moment in time within each suit. In a newly installed exhibition, “Until,” at Mass MoCA, Cave is “putting you into the belly of a Soundsuit.” Across the gallery, Cave has installed millions of plastic beads, 16,000 wind spinners, and thousands of shoelaces to create an immersive experience—an explosion of color, texture, and sound.