Gallery Network

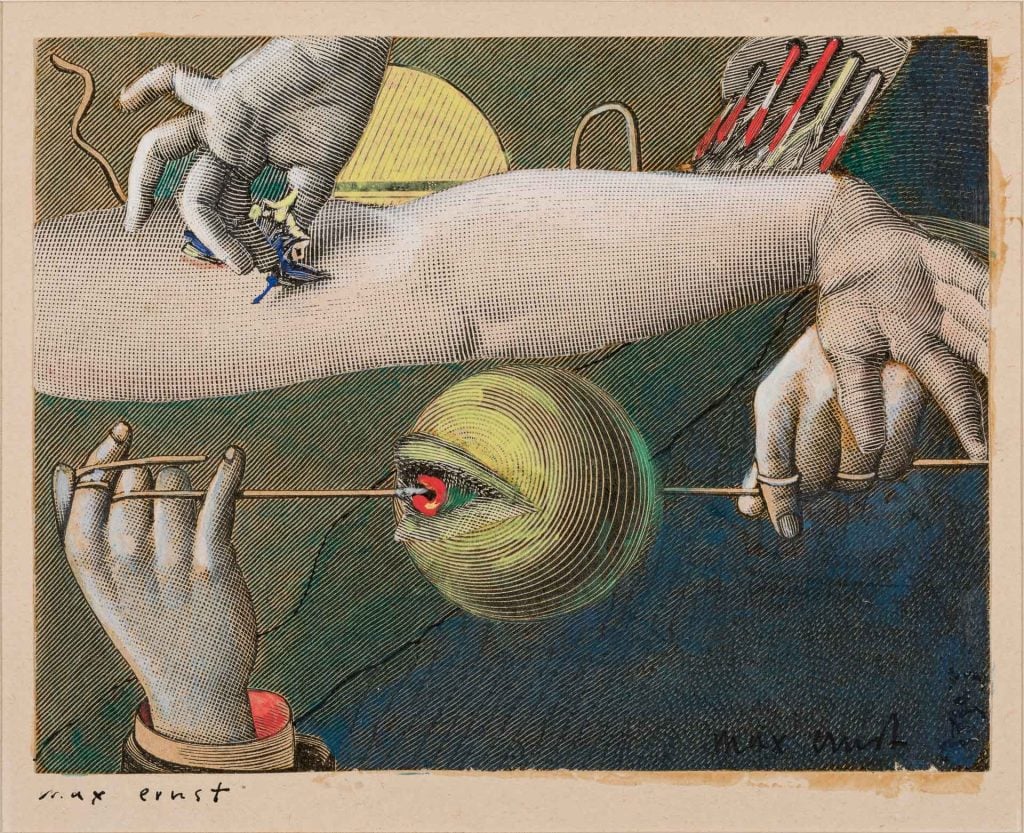

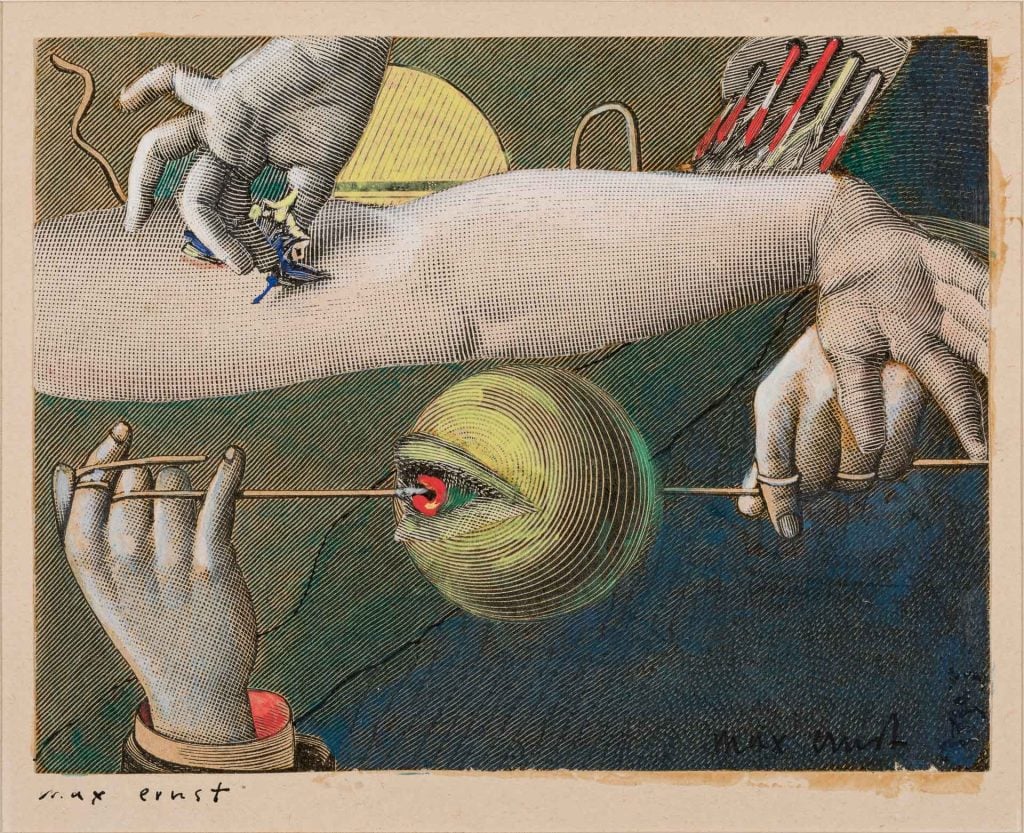

Max Ernst’s Outsized Impact on Modern Art Is Showcased in This Meticulously Curated Paris Show

Presented by Galerie Malingue, "Max Ernst: The Perfection of Chance" revives brings new light to the artist's enduring legacy.

Presented by Galerie Malingue, "Max Ernst: The Perfection of Chance" revives brings new light to the artist's enduring legacy.

Artnet Gallery Network

A pivotal figure within the development of Modern art at large, and more specifically the movements of Dada and Surrealism, German artist Max Ernst (1891–1976) pioneered new ways of approaching visual art, which were disseminated throughout Europe via his work. Coinciding with the centennial of Surrealism, Paris-based Galerie Malingue is presenting the solo exhibition “Max Ernst, La Perfection du Hasard,” or “Max Ernst: The Perfection of Chance,” comprised of roughly 20 carefully selected works that demonstrate his avant-garde practice and highlight the importance of his oeuvre to the trajectory of art history.

Max Ernst, Le Couple (1923). Courtesy of Galerie Malingue, Paris.

On view through November 29, 2024, “The Perfection of Chance” showcases both the technical skill and creative vision of Ernst, which, together, led to visually lavish, even fantastical compositions that engage with universal truths. Ernst famously was a founder of the Cologne Dada group in 1919, and several years later, in 1922, fell in with the Surrealists, which greatly influenced his career and practice, identifying with their questioning of reality and interest in psychology and the subconscious. Within the present exhibition, the bulk of works on view are dated from 1920s and 1930s, illustrating this momentous period in Ernst’s life and career.

Max Ernst, Sun over the Forest (1927). Courtesy of Galerie Malingue, Paris.

One of the key developments in Ernst’s work was the broadening of his material approach, and like the Surrealists, he experimented with collage, integrated compositions, and, though later, frottage and grattage (rubbing and scratching) as well as decalcomania, which is the process of transferring images or designs from paper on to glass or porcelain. Employing and combining these types of new techniques as well as others from his repertoire led him to increasingly explore the potential of landscape, representation, and figuration—often pushing them to their limit. The result is a body of work that defies straightforward reading, and instead invites viewers into the imaginary depths of Ernst’s imaginary worlds, replete with otherworldly foliage, skylines, and populated by chimerical forms.

Max Ernst, Forêt pataphysique or Dernière Forêt (1970). Courtesy of Galerie Malingue, Paris.

Standout works from the show that exemplify this type of investigational, playful mode of artmaking by Ernst include Le Couple (1923). Here, reinforced by the work’s title “The Couple,” the figuration is rendered obliquely, composed of various reproduced scraps of what appears to be lace, swathes of paint, and cheekily placed “eyes.” Elsewhere, in Sun Over the Forest (1927), without the title, one might not immediately recognize the reference to trees, as instead they are shown as stark vertical lines, and the sun is simplified to a thick blue ring surrounded by a finer one of yellow. Through these works and the show together, Ernst’s contributions not only to Surrealism are made manifest—but his influence on the evolution of abstraction as well.

“Max Ernst: The Perfection of Chance” is on view at Galerie Malingue, Paris, through November 29, 2024.