On View

María Magdalena Campos-Pons Shows Her Santería-Influenced, ‘Poetic Surrealist’ Art at the Brooklyn Museum, a Long Overdue New York Survey

The artist's last major museum survey was in Indiana back in 2007.

The artist's last major museum survey was in Indiana back in 2007.

Sarah Cascone

You may not know the name María Magdalena Campos-Pons yet, but the Cuban-born artist—who draws on the global legacy of colonialism and her own family history—has long built up significant art-world credentials outside of New York.

In addition to appearing in prestigious international exhibitions such as Documenta 14 and the Sharjah Biennial, she has also had her work acquired by institutions including New York’s Museum of Modern Art; the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.; the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. Just this week, she was named a 2023 MacArthur Fellow, an honor that comes with a $800,000 grant.

Now, those pieces are all on loan to the Brooklyn Museum—which added Campos-Pons to its own collection earlier this year—for “Behold,” the 64-year-old artist’s first museum survey show since 2007 (at the Indianapolis Museum of Art), and her first major New York exhibition.

The first work on view, an ambitious installation titled Spoken Softly With Mama, “is just art history canon, period,” Carmen Hermo, associate curator at the museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, told me during a recent tour of the exhibition.

“María Magdalena Campos-Pons: Behold” at the Brooklyn Museum with her sculptural installation Spoken Softly With Mama (1998). Photo by Paula Abreu Pita.

First shown at MoMA in 1998 and now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the piece combines video projection, sound, cast glass sculpture, and hand embroidery in a moving tribute not only to the artist’s female relatives, but the broader history of Black women’s domestic work, both for their own families, and in the employ of white ones.

“In the videos, you see Magda kind of performing these poetic surrealist type of evocations of that labor,” Hermo said.

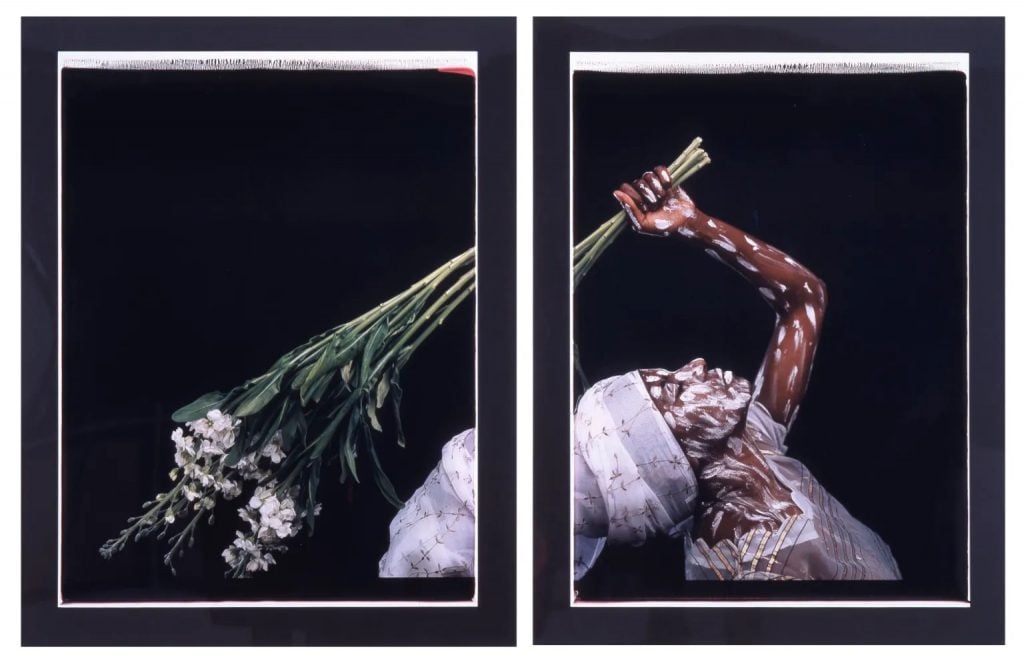

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Secrets of the Magnolia Tree (2021). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo ©María Magdalena Campos-Pons.

Hermo organized the show with Mazie Harris, a curator at the Getty, where the show will conclude a tour that includes stops at the Nasher Museum of Art in Durham, North Carolina, and the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, bringing together a selection of more than 50 works that engage with complex subjects such as motherhood, racial identity, the legacy of slavery, police brutality, and the migrant crisis. (A tribute to Breonna Taylor is on loan to the Brooklyn Museum from the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.)

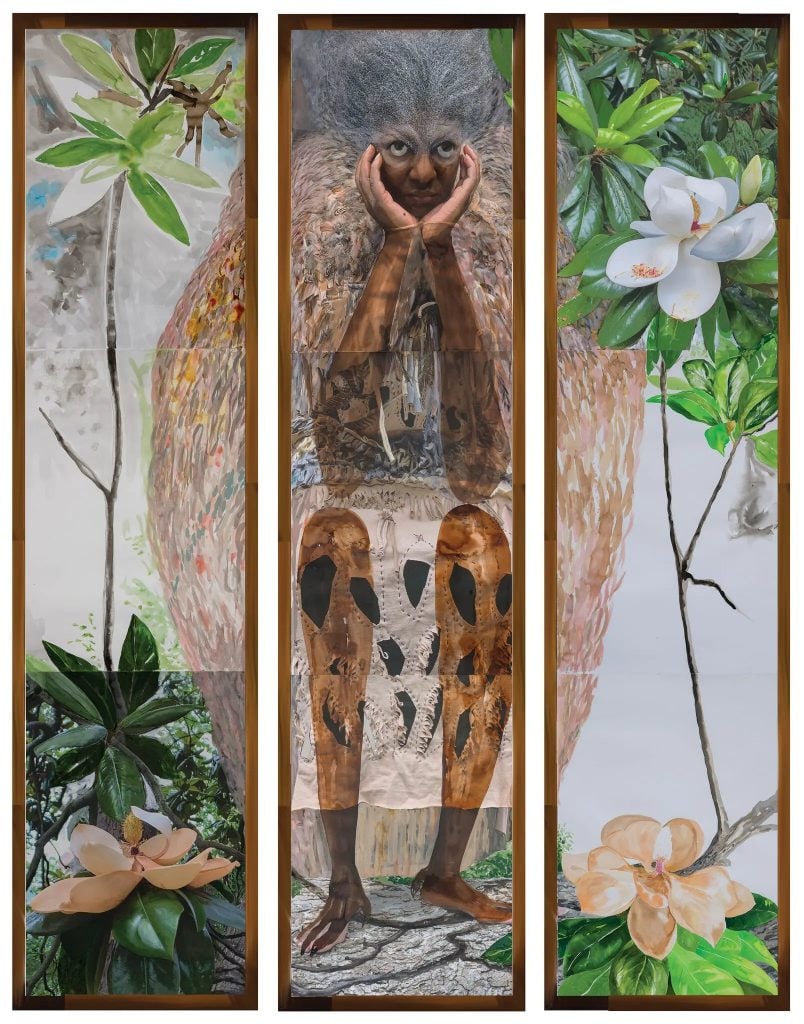

A photographer, painter, sculptor, and performance artist, Campos-Pons was born in 1959, the year Fidel Castro came to power. In defiance of the official state atheism of her youth, the artist taps into her spirituality in her work, often referencing Santería, an African diasporic religion with roots in West Africa’s Yoruba faith that has influences from a wide range of cultures, including Catholicism.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Red Composition (1997), from the series “Los Caminos (The Path).” Collection of Wendi Norris. Photo ©María Magdalena Campos-Pons.

Campos-Pons’s grandmother was a Santería priestess; her father, an herbalist. Key to many pieces are Santería’s pantheon of Orishas, seven deities said to have traveled to the Americas during the slave trade to safeguard their people.

One self-portrait depicts Campos-Pons as Yemaja, the mother of all Orishas, naked from the waist up save for blue body paint of the ocean waves. The artist is posing with two baby bottles of her own breast milk and a hand-carved wooden boat, symbolizing the goddess’s nourishing of her people even as they are forced to leave behind their homes.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Untitled (Breast and Bottle Feeding) (1994), from the series “When I Am Not Here/Estoy Alla.” Collection of the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth. Photo ©María Magdalena Campos-Pons.

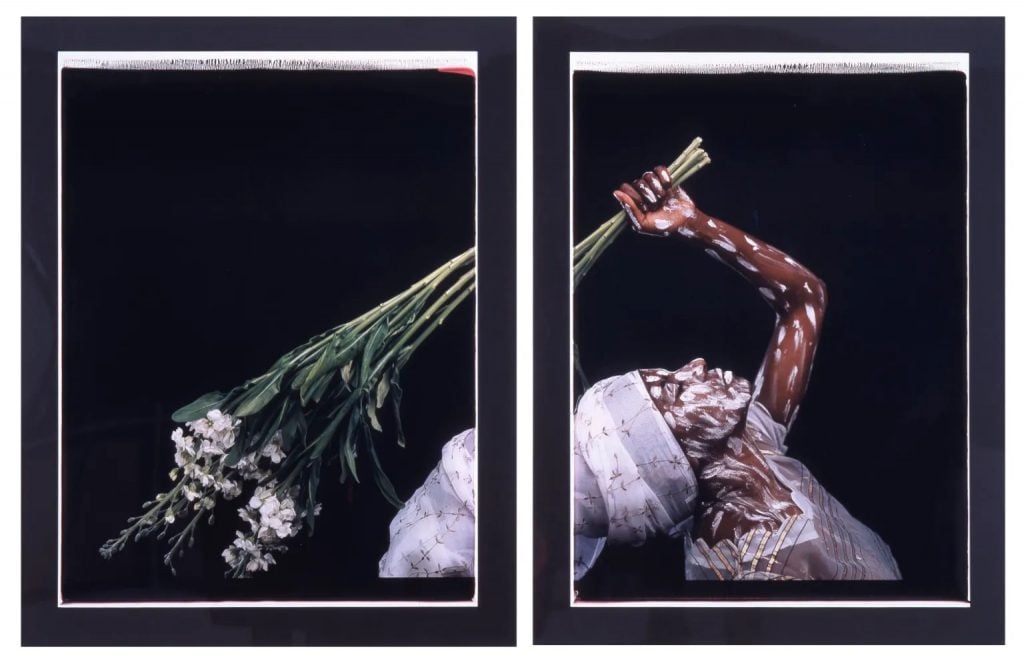

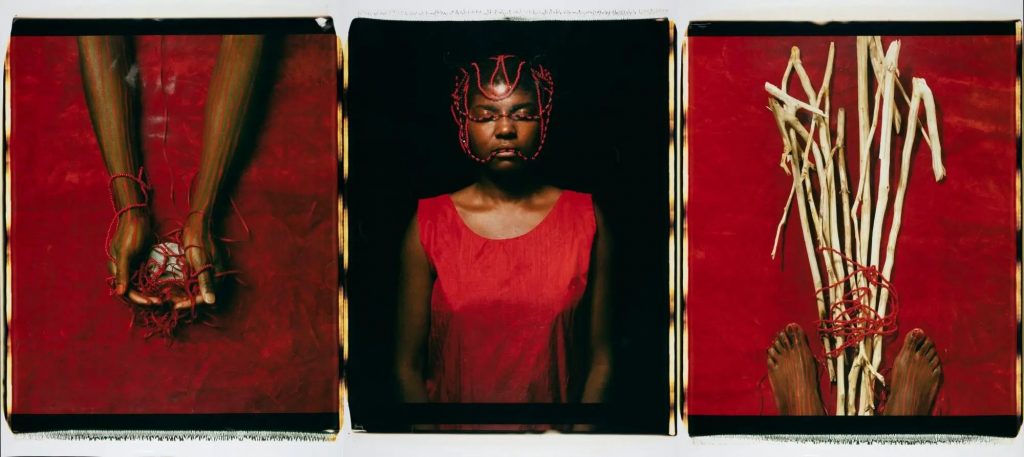

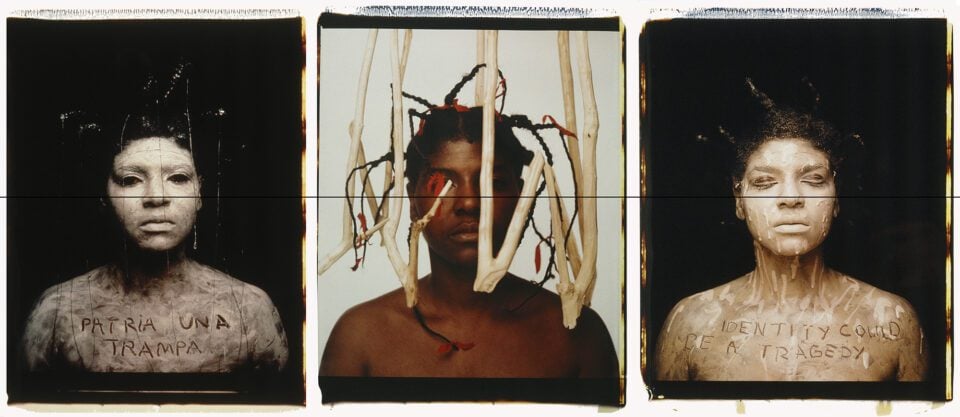

A significant portion of the exhibition is dedicated to the artist’s large-scale Polaroids, 20-by 24-inch prints she began creating as part of a multi-year residency with the photography company in the 1990s. Campos-Pons uses the individual images to create unique multi-panel photographs that are monumental in scale and look like performances frozen in time.

“That idea of the combination of the fragments coming together as one is so crucial to the work. She also describes it as the topography of diaspora,” Hermo said. “This idea that you’re taking multiple experiences and dislocations and geographies and connections and sort of combining them all together.”

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, When I Am Not Here/Estoy Allá, Tríptico I, (1996). Photo ©María Magdalena Campos-Pons.

Forced to leave an increasingly unstable Cuba following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Campos-Pons moved first to Canada before settling in Boston. (She’s called Nashville home since 2017.) Unable to visit her family for years, the artist imbued her work with a sense of homesickness and loss, but also a rootedness in her identity and family history, as well as her physical body.

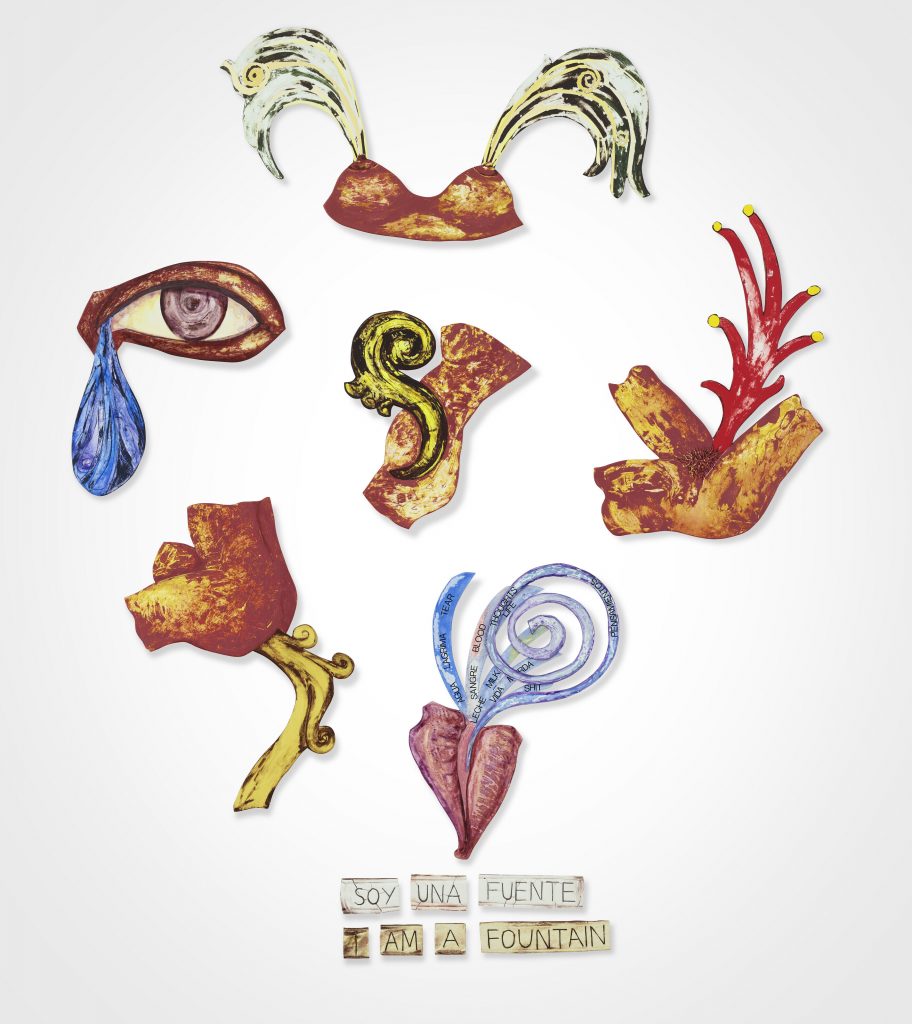

The 1990 mixed-media wall-relief sculpture Soy una Fuente (I Am a Fountain), just acquired by the Detroit Institute of Arts at Christie’s in March—where it sold for four times the high estimate—illustrates many of those themes and Campos-Pon’s strong feminist underpinnings.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Soy una Fuente (I Am a Fountain), 1990. Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo ©María Magdalena Campos-Pons.

“It has these elements of the body fragmented again, but effusive, leaking,” Hermo said. “There’s menstrual blood, there’s shit, there’s tears, there’s breast milk, there’s a little fetus floating there in the center, and then what Magda describes as the most potent output of a woman—which is her words, coming from the mouth. It’s this idea of the artist defining herself, as a body, as a creator of life, but then also specifically as a Black woman.”

“María Magdalena Campos-Pons: Behold” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, September 15, 2023–January 14, 2024.