Law & Politics

A Performer in Marina Abramović’s MoMA Show Is Suing the Museum for Failing to Address Repeated Assaults

The plaintiff claims to have been groped seven times during the run of the 2010 exhibition.

The plaintiff claims to have been groped seven times during the run of the 2010 exhibition.

Taylor Dafoe

A man who performed nude in the 2010 Marina Abramović exhibition, “The Artist is Present,” at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is now suing the institution for allowing him to be groped on multiple occasions during the run of the blockbuster show.

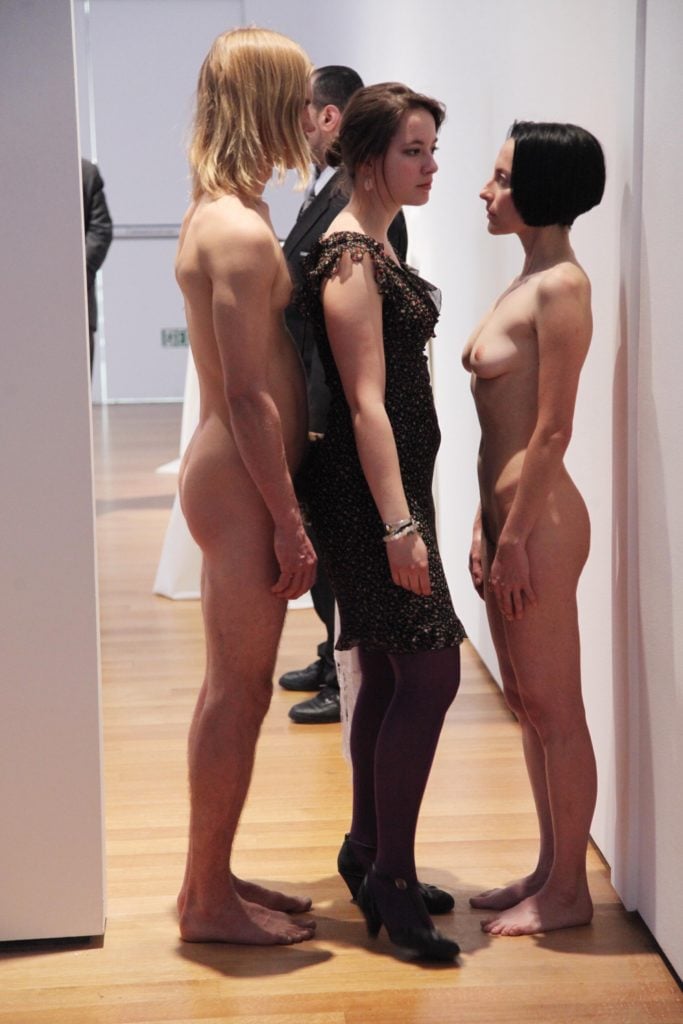

The plaintiff, John Bonafede, detailed his allegations in a complaint reviewed by Artnet News, filed Monday in a New York court. He claims to have been assaulted on seven different occasions while participating in a restaging of Abramović’s seminal participatory artwork, Imponderabilia (1977), which features naked models standing face-to-face in a narrow doorway while passing gallery-goers attempt to squeeze through.

“The circumstances of each of these assaults was eerily similar,” the complaint alleged. In each case, the assaulter—always an “older male”—would “drop his hand, covertly reach between [Bonafede’s] legs, and fondle and/or grope [his] genitals, lingering for a moment before moving through into the next gallery room.”

Marina Abramović and Ulay, Imponderabilia (1977), restaged by performers in “Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present” at the Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo: Will Ragozzino. ©Patrick McMullan.

Bonafede said that he did not report the first assault, which left him in a “state of shock,” but reported all subsequent incidents to MoMA’s security personnel. He was later informed that the four individuals he reported had been ejected from the museum. One was a MoMA “corporate member” who had his membership revoked.

However, because MoMA did not share the identities of his assaulters, Bonafede said he was unable to press individual charges against them.

He wasn’t the only Imponderabilia participant subjected to inappropriate behavior during “The Artist is Present.” Reports of groping, verbal harassment, and even stalking were covered in news articles at the time. Bonafede’s lawsuit cites these articles as evidence that MoMA knowingly put Imponderabilia performers in “highly vulnerable and risky positions on a daily basis.”

He claimed the museum turned a “blind eye” and “failed to establish, implement, or enforce policies and procedures to protect the health, safety, and welfare of… performers, and to prevent them from being sexually assaulted in the first place.” The plaintiff also pointed out that the exhibition included no signs indicating that the sexual touching of performers was not permitted.

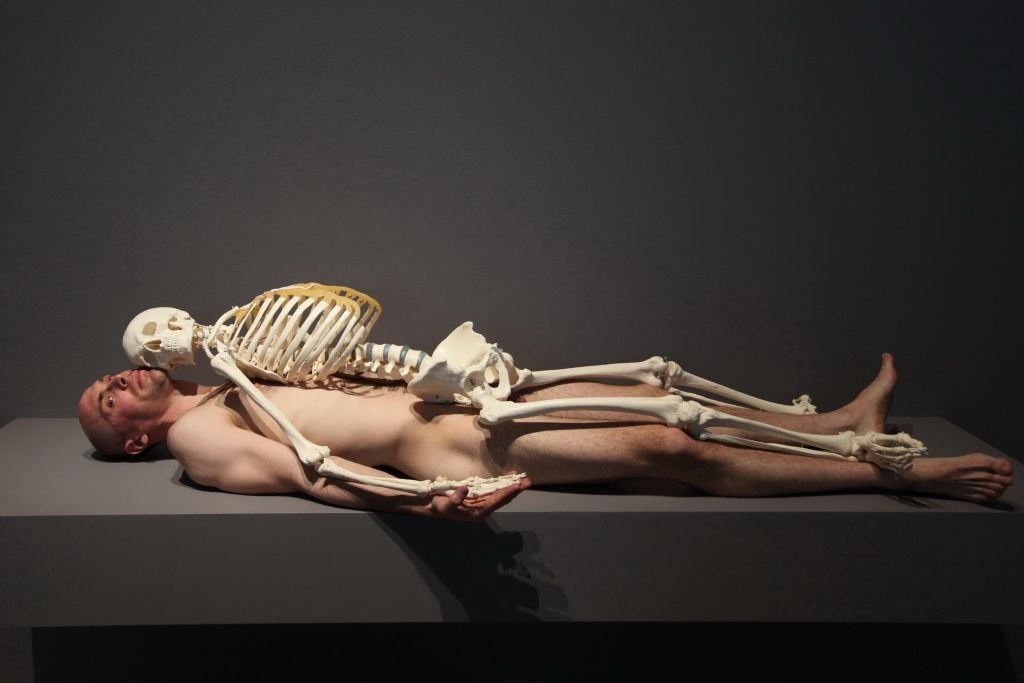

John Bonafede performs in “Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present” at the Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo: Will Ragozzino/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

With the complaint, Bonafede is seeking a jury trial to determine the damages he is owed for the “emotional distress and harm” caused by “MoMA’s negligence.”

Representatives from the Museum of Modern Art did not immediately return a request for comment.

Bonafede’s lawsuit was filed under the New York Adult Survivors Act, which lifted the statute of limitations on sexual assault cases for a one-year period between November 2022 and November 2023. According to the Daily Beast, Bonafede was granted permission to file his complaint after the act’s window lapsed last fall.

More Trending Stories:

A Case for Enjoying ‘The Curse,’ Showtime’s Absurdist Take on Art and Media

Artist Ryan Trecartin Built His Career on the Internet. Now, He’s Decided It’s Pretty Boring

I Make Art With A.I. Here’s Why All Artists Need to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Technology

Sotheby’s Exec Paints an Ugly Picture of Yves Bouvier’s Deceptions in Ongoing Rybolovlev Trial

Loie Hollowell’s New Move From Abstraction to Realism Is Not a One-Way Journey