Art & Exhibitions

Self-Taught Artist Marlon Mullen’s MoMA Debut Is a Joyful Ode to Art Magazines

The artist creates loving and highly individualized portraits of art magazine covers, engaging with the art world on his own terms.

Art about art is catnip for aesthetes. Art about art magazines is sure to be a magnet for people like me—I spent a decade in the trenches at Art in America. So over the years, I’ve always loved seeing California artist Marlon Mullen’s painted interpretations of covers and advertisements from publications like Artforum, Art in America, and Frieze. Seeing the covers is like seeing old friends, and witnessing his visual commentary on them, the way he transforms them with graphic riffs in vivid colors, well, it’s like seeing an old friend who is trying out a dashing new style that really suits them.

So when New York’s Museum of Modern Art announced in the fall that it would organize a Mullen solo show in its Projects gallery, which is open to the public free of charge, it was great news. The show itself is even greater news. With a daring installation based on input from the artist himself and some judicious choices in terms of didactic material, the whole show, organized by chief curator of painting and sculpture Ann Temkin with support from curatorial assistant Alexandra Morrison, is a triumph.

Installation view of “Projects: Marlon Mullen” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo courtesy of MoMA.

The show is a joyous occasion partly because he’s not the kind of artist you might expect to see in a solo show at one of the world’s greatest museums. Born in 1963 in Richmond, California, Mullen has long been based at his hometown’s NIAD Art Center (“Nurturing Independence through Artistic Development”), which hosts and supports Bay Area artists with developmental disabilities; in fact, this is the first MoMA showcase for an artist with such disabilities. As it happens, the museum has a long history of showing folk art, Outsider artists, and untrained practitioners—favored terminology has changed over time—so while this is a special high water mark, it doesn’t come completely out of the blue.

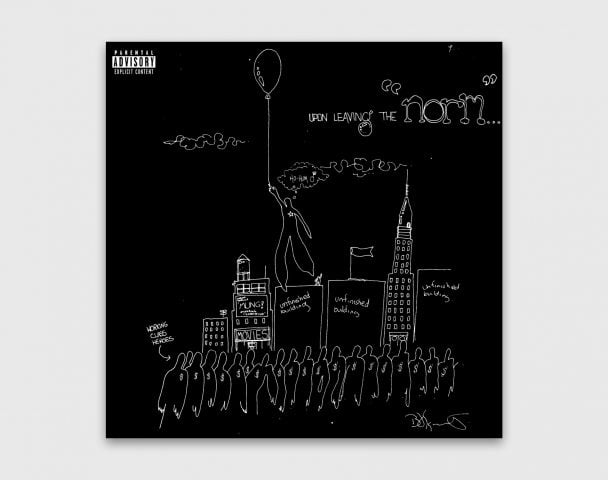

Marlon Mullen, Untitled? (2024). Courtesy of the artist, NIAD Art Center, and Adams and Ollman. Photo: Chris Grunder.

The paintings are a delight. Mullen’s rendition of an advertisement for a show of early Warhol paintings at New York gallery Blum Helman, for example, plays havoc with the unmistakable face of Marilyn Monroe: her sexy, slight smile and heavy-lidded gaze turn into a look of shock, mouth seemingly agape, painted brows hovering far above her eyes. And “Warhol” appears not above her face, as in the ad, but rather superimposed on her hair, as if the shadows between her blonde locks formed the Pop artist’s name.

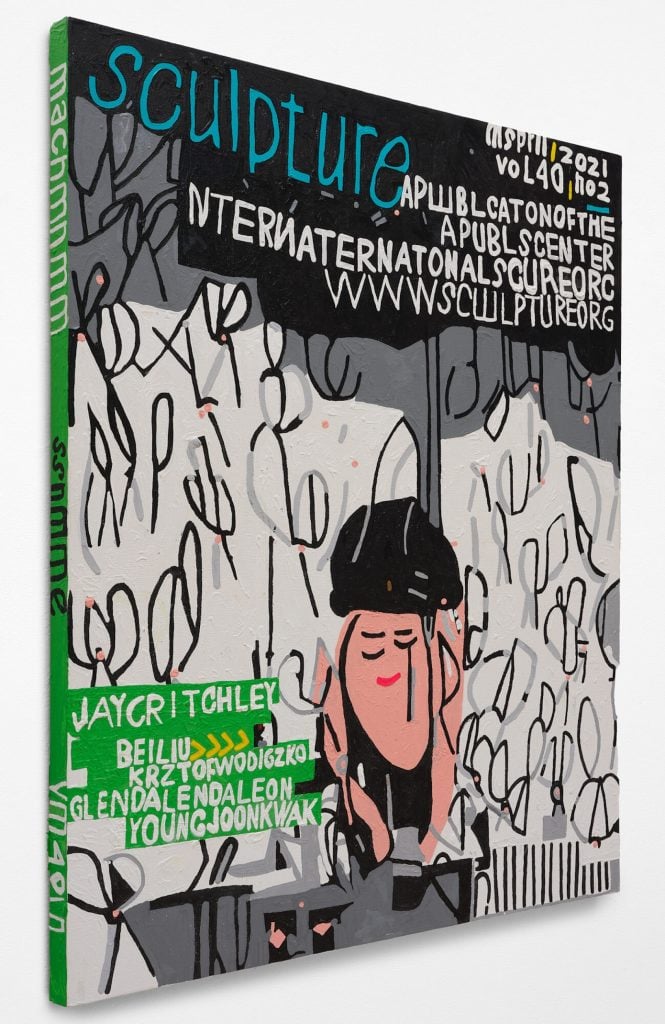

Marlon Mullen, Untitled (2018). Photo: Charles Benton.

Mullen takes even greater liberties with a February 2004 Art in America cover featuring a detail of James Rosenquist’s painting House of Fire (1981), in which multiple tubes of lipstick seem to bear down like rockets on a bucket that floats in front of a window. None of those motifs survive Mullen’s treatment, which imposes a square shape on the magazine’s triangular layout and preserves only the deep reds and various shades of blue in what has, apart from the magazine’s title, become an abstract composition.

Installation view of “Projects: Marlon Mullen” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo courtesy of MoMA.

In a thoughtful addition, the museum has included a display case with a handful of the very copies of the magazines Mullen himself works from, so his innovations are plain to see. It’s illuminating to look at the May 1997 Artforum cover in which a gawky teenager stares out at us from Rineke Dijkstra’s 1992 photo Kolobrzeg, Poland, and then turn around and see Mullen’s interpretation, where the magazine’s logo and even the girl herself have shrunk, while a brushy version of the sky dominates—even as a UPC barcode encroaches from the corner.

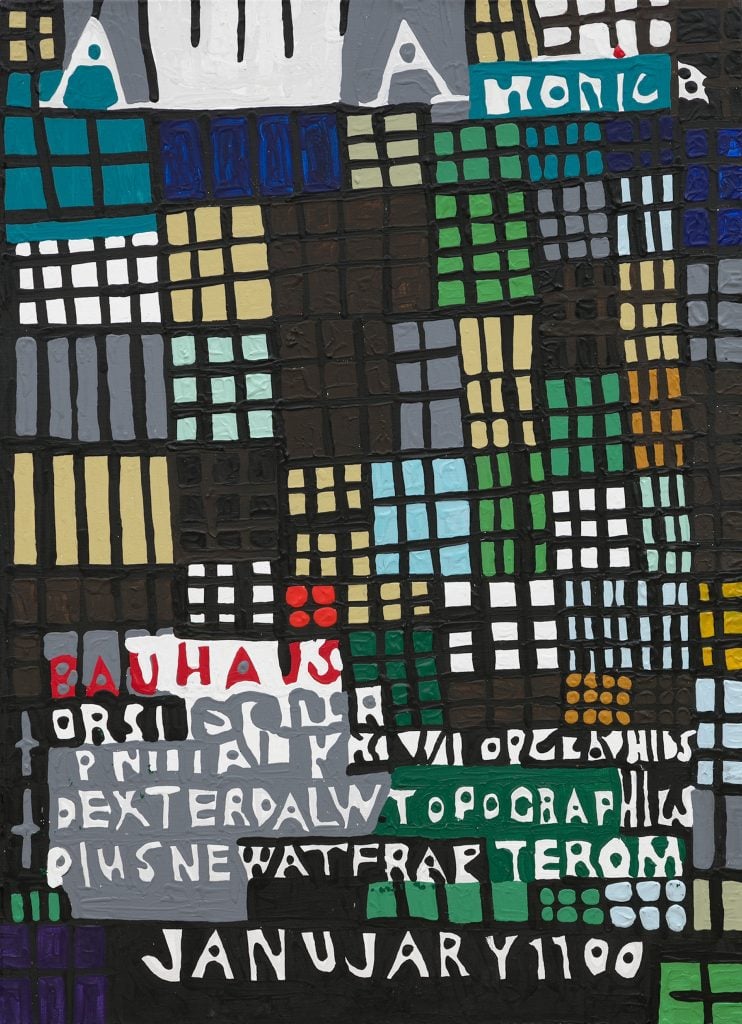

Marlon Mullen, Untitled (2016).

But I’m able to make those comparisons I made earlier because the museum has also provided a website where each painting is lined up next to its source. It is not just illuminating but also hilarious to regard the September 2015 Artforum cover where a beatifically glowing infant gazes out from Torbjørn Rødland’s photo Baby (2007), and then look, high up on the wall, to see Mullen’s untitled 2015 interpretation, in which the baby has fattened up into something resembling an infant Jabba the Hutt, and is seemingly covered in pimples.

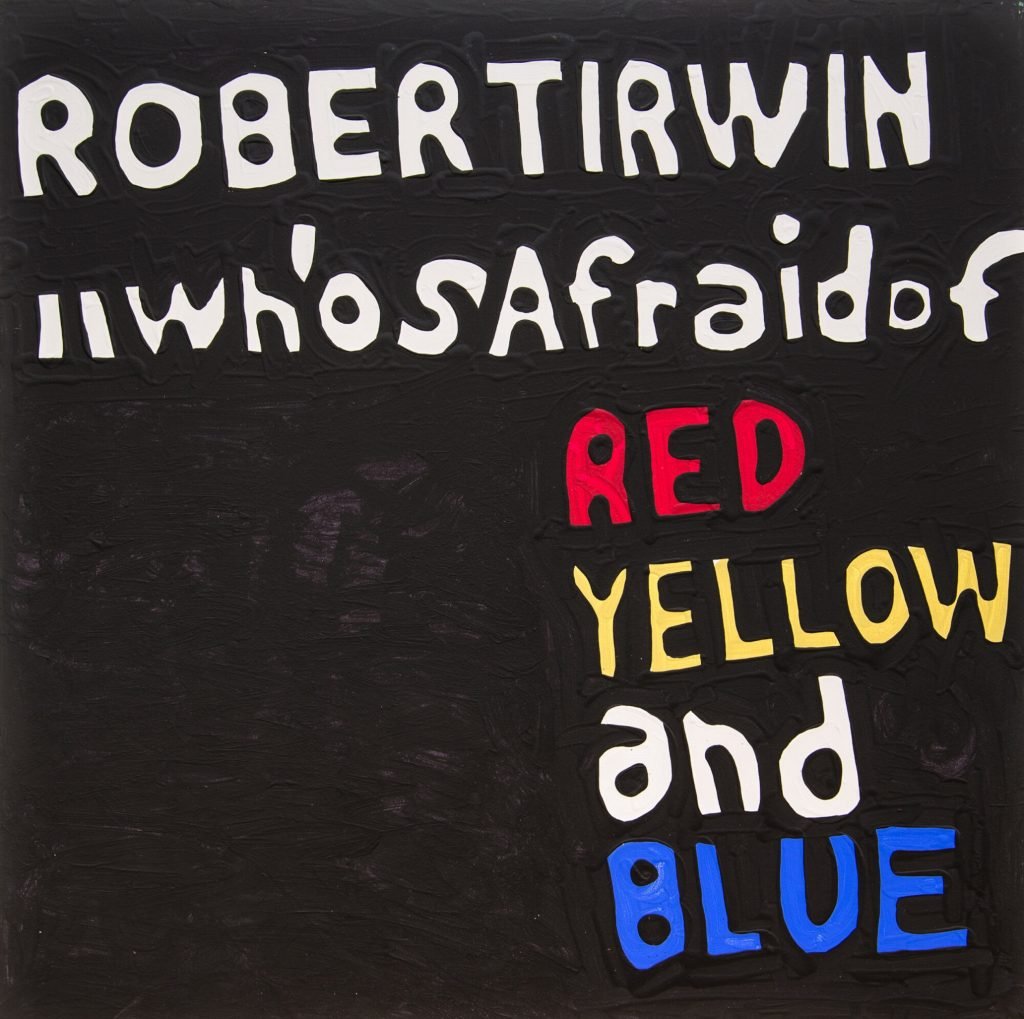

Marlon Mullen. Courtesy the artist and NIAD Art Center.

It’s also great fun to know, if you can’t figure it out from the paintings themselves, just how many artists’ work—not to mention the art designers’ treatments of the images and the cover texts—come in for Mullen’s revamps: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bernd & Hilla Becher, René Magritte, Kerry James Marshall, Claes Oldenburg, Jenny Saville, and Sarah Sze are among them.

Besides the joy of the paintings and the edification of the side-by-side comparisons, the show is notable for being so successful even in a challenging space. Its ceiling is over 26 feet high, but the paintings, even at modest scale, command the eye. In a quirky idea that came straight from the artist, three paintings hang very high on the wall just to your right as you enter, and the far wall has an effective salon-style hang.

Installation view, “Projects: Marlon Mullen,” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

MoMA also went the extra mile to make the space welcoming. Museum environments can be unforgiving, especially in sonic terms, with all their hard surfaces making for an unpleasant experience for anyone—not to mention neurodivergent people who might be especially sensitive to sound. The museum accounted for those visitors in spades, with a not-unappealing gray carpet that goes a long way to deaden sound, and downright attractive “acoustic sofas” from Snowsound that absorb noise and that you can even carry to your preferred spot for viewing the show. They really ought to carry them in the MoMA Design Store across the street.

“Projects: Marlon Mullen” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, through April 20, 2025.