People

Longtime Walker Art Center Director Martin Friedman Dies at 90

He ran the show at the Walker for three decades.

He ran the show at the Walker for three decades.

Brian Boucher

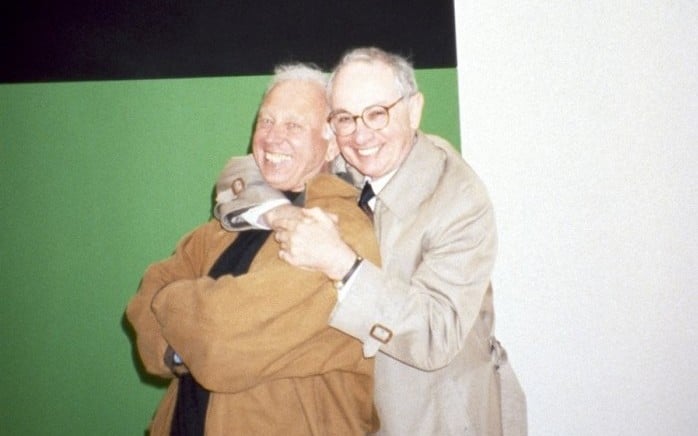

Martin Friedman in 2004. Photo courtesy Walker Art Center.

Martin Friedman, who oversaw Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center for three decades, died on Monday at 90 at his home in New York City. As the institution’s third and longest-serving director, he oversaw the construction of a new building and developed a beloved new public space, the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. During his career, he instituted forward-looking programs highlighting performance and new media, ahead of many other American museums.

Friedman had undergone chemotherapy treatment, but a family friend tells the Minneapolis Star-Tribune that congestive heart failure was likely the immediate cause of death.

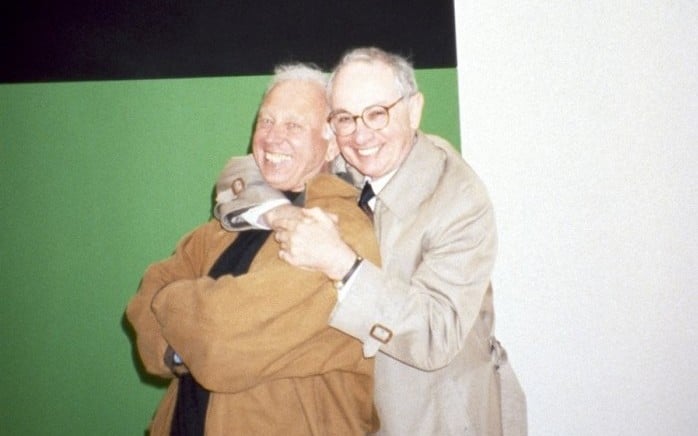

Martin Friedman, right, with Ellsworth Kelly in 1989. Photo courtesy Walker Art Center.

Born in Pittsburgh, Friedman earned an MA in studio art and art history at the University of California at Los Angeles. After teaching high school and college art classes in LA, he won a fellowship to study African art in Belgium. He was hired as a curator at the Walker in 1958, and succeeded Harvey Arneson when he departed for the Guggenheim Museum in 1961. Friedman was then just 36 years old.

While a Walker curator, he had already distinguished himself with exhibitions like The Precisionist View in American Art (1960), including Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Charles Sheeler.

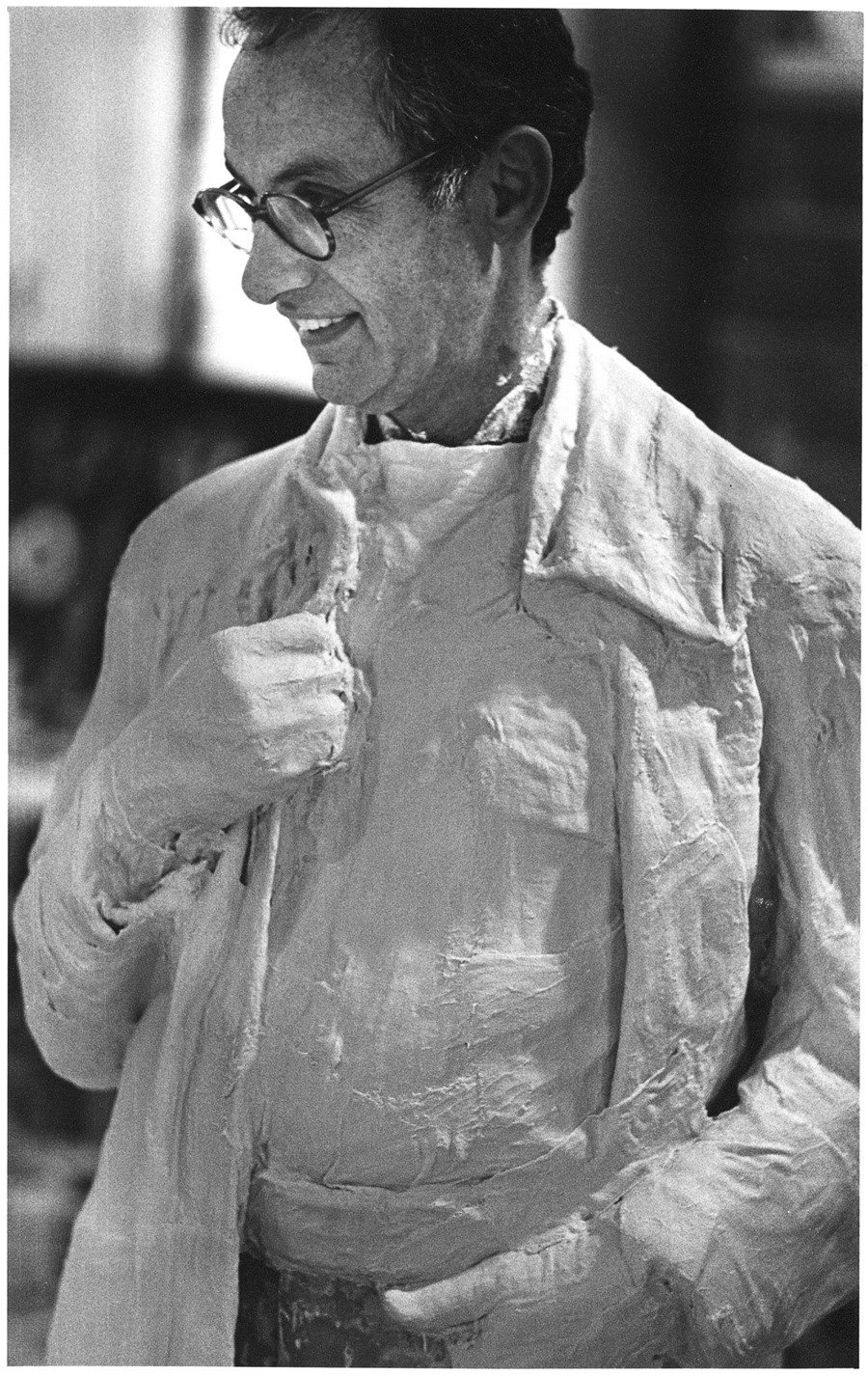

Friedman poses for a plaster sculpture by George Segal, 1978. Photo courtesy Walker Art Center.

Friedman also commissioned a new museum building designed by architect Edward Larrabee Barnes, which opened in 1971. Art historian Barbara Rose is quoted on the Walker’s website, stating that Barnes’s building was “designed on a human scale for people to move through at a leisurely pace and for artists to show works in without having to compete with the architecture.”

One of his signature achievements was the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, a public-private partnership that opened in 1988 on an 11-acre plot across from the museum, and contained the now-iconic sculpture Spoonbridge and Cherry by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen.

Known for engrossing installations that he hoped would spread what he called the “thrilling” effect of contemporary art, he also took a personal interest in the museum’s interns and trainees, as Rothfuss recalls in a remembrance on the museum’s website. While editing a text of hers, he once admonished her, “You’re not writing for Artforum,” she recalls.

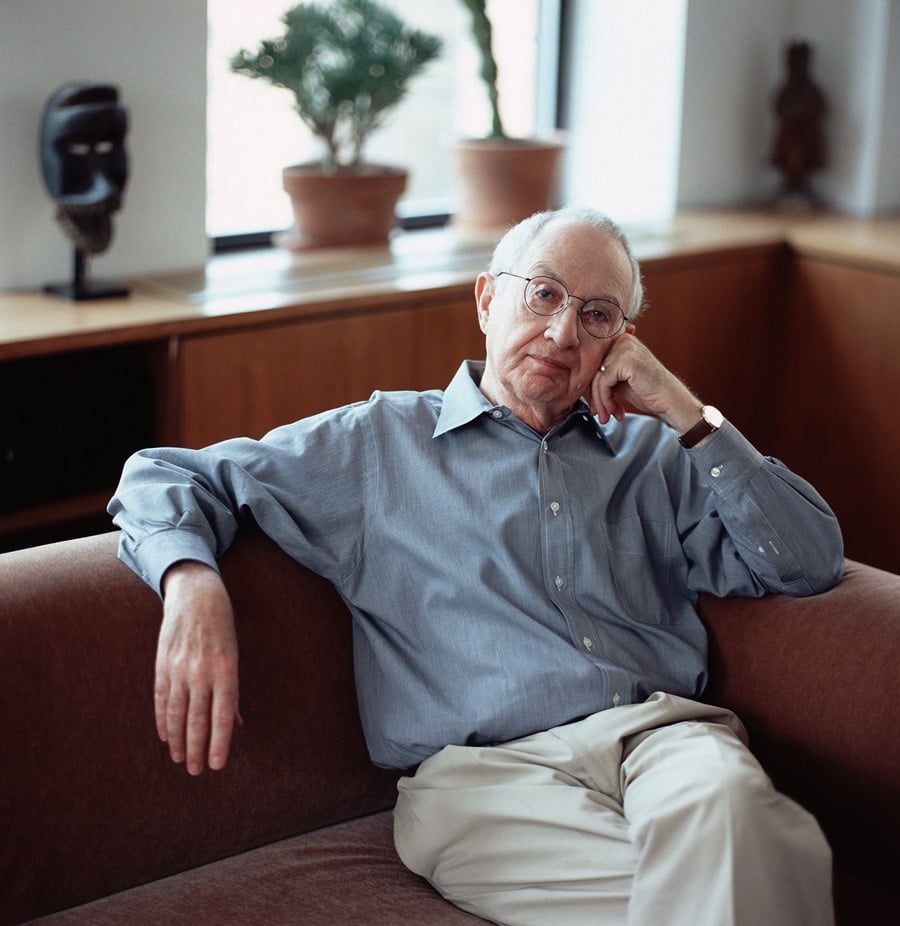

Friedman, right, with Marcel Duchamp in 1965. Photo courtesy Walker Art Center.

He was also known for fastidiousness.

“I could have killed him three times a week because he was so relentless,” former Walker curator Graham Beal, now retired director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, told the Star-Tribune. “But from Martin I learned that you don’t start with compromise in mind. You start with what you want and don’t settle for anything but the best.”

Friedman left the Walker in 1990, after which he advised the Nelson Atkins Museum, in Kansas City, on sculptural acquisitions as well as advising and curating public art for New York’s Madison Square Park.

The museum has published a series of recollections by Friedman on its website, including accounts visits to Minneapolis by John Cage and Marcel Duchamp, and a trip to New York to meet Joseph Cornell. More are to come.