Art & Exhibitions

Martin Wong Show Reveals the Artist’s Wild San Francisco Roots

His self-taught but savvy style has its roots in radical 60s counterculture.

His self-taught but savvy style has its roots in radical 60s counterculture.

Ben Davis

“Basically everything I paint is in my immediate neighborhood, where I ended up,” Martin Wong said in a lecture in 1991. “So, people assume that I’m a local New York painter, but really I’m from San Francisco.”

That could also more or less be the thesis of “Martin Wong: Painting is Forbidden,” currently up (through April 18) at the Wattis Institute in San Francisco. Organized by members of the Curatorial Practice program at the California College of the Arts, the modest but wide-ranging show brings together some 150 pieces, both works by the artist and previously unseen ephemera. It shows an overlooked side of a major figure, but also, through his story, offers a glimpse of the now-passed creative world of 1960s and 70s counterculture that formed him.

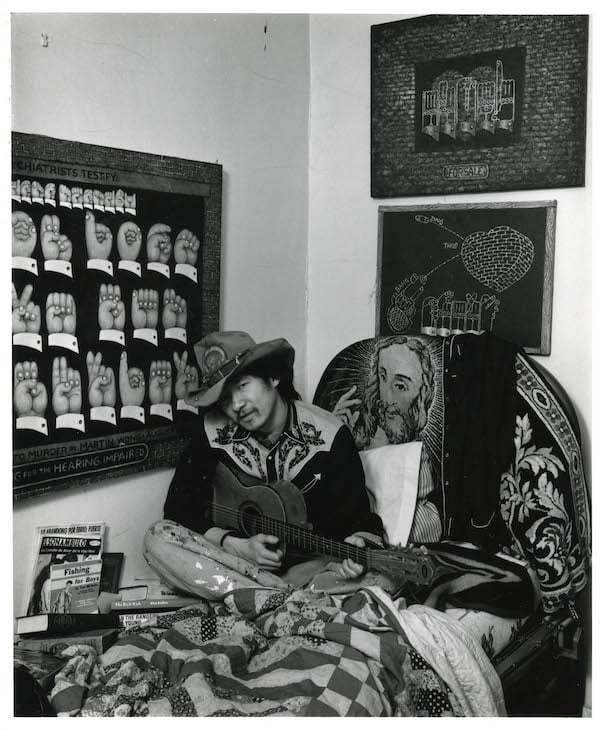

These days, Wong has a kind mythic cachet (see Destined For a Garage Sale, Martin Wong’s Collection Is Saved by Danh Vō and the Walker Art Center), connected to his life “where he ended up,” that is, the Lower East Side in its gritty-glamorous 70s and 80s phase (a few years after that talk at the San Francisco Art Institute, Wong returned home to the Bay Area, where he would die of an AIDS-related illness in 1999). He amassed one of the great collections of classic New York graffiti art, which was displayed at the Museum of the City of New York’s “City as Canvas” show this past year, and is burned into the memory of the era through his defiantly colorful, cowboy-hatted persona.

Martin Wong in 1985.

Photo: Peter Belamy, courtesy of the Estate of Martin Wong and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York.

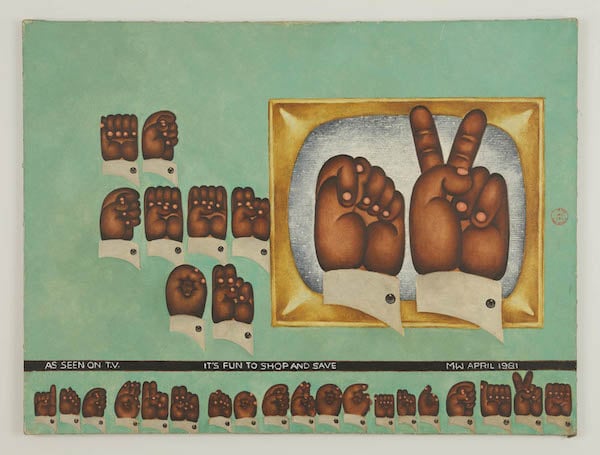

Artistically, Wong’s paintings cast a long shadow over everything else (a selection was featured as part of the show-within-a-show at the Whitney Biennial last year). His self-taught but savvy style channels the look of urban folk art, with his own quirky set of leitmotifs: desolate landscapes of brick walls and chain link fences that evoke the era’s disarray; rows of cartoon hands spelling out phrases in American sign language; kissing firemen; images of, or inspired by, the life and art of Miguel Piñero, the playwright and founder of the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, as well as Wong’s lover and sometimes collaborator.

As Seen on T.V.—It’s Fun to Shop and Save” (1981).

Courtesy of the Estate of Martin Wong and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

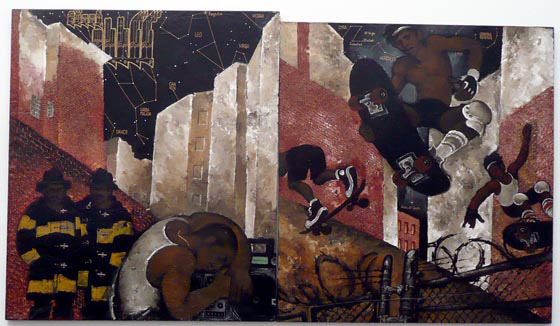

The Wattis show, sadly, does not give a true sense of Wong’s abilities as a painter. It features only one large canvas, the diptych Sweet ‘Enuff (1988), on loan from the de Young Museum. On the left panel, a pair of firemen observe a man, collapsed or asleep, hunched over a boombox. In the facing panel, three youths are suspended in the air in a heroic moment of skateboarding derring-do, sailing improbably towards freedom over the crest of a barbed-wire fence. At the top of the canvas is one of Wong’s classic romantic touches: the sky is webbed with gold, forming the outlines of hands spelling out the painting’s title in sign language, and tracing the constellations in the sky, each of them labeled—Leo, Virgo, Ursa Major.

Martin Wong’s Sweet Enuff (1988) at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum.

Photo: Walter Robinson.

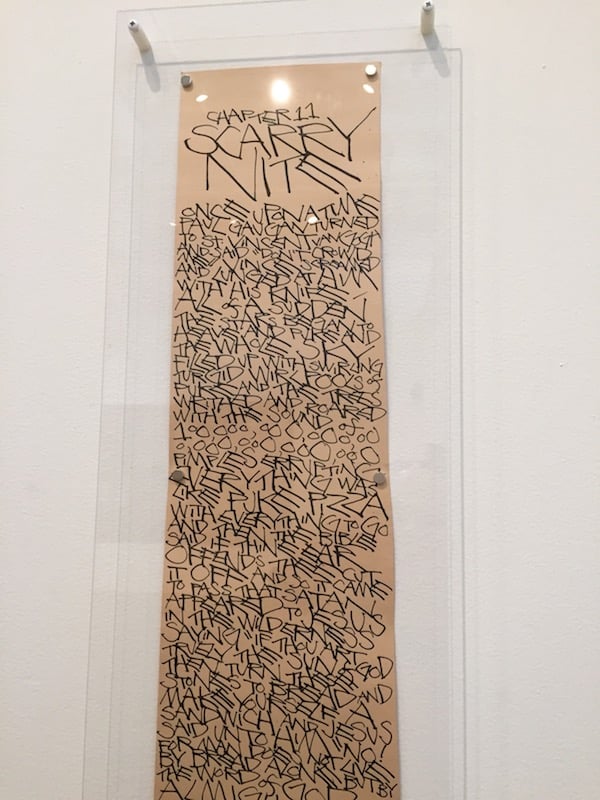

Most of the Wattis show is dedicated to Wong’s more peripheral material, much of it from before he moved to New York in 1978: small early ceramics, some of angels and monsters, from his student days at Humboldt State University in Eureka, California; sketchbook pages; and a large selection of scroll-like text paintings rendering his febrile poems in dense, spidery calligraphy. The text paintings capture a very characteristic tension in Wong’s whole artistic approach: his writing radiates passionate and urgent need to say something; but the stylized-to-the-point-of-illegibility style puts up a barrier, making that something hard to access.

Detail of Martin Wong scroll painting at the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts.

Photo: Ben Davis.

It is the trove of artifacts related to his early-70s stint with the queer performance troupe the Angels of Light that most fires the imagination here. The Angels had emerged in 1970 as a particularly intense manifestation of the era’s countercultural experimentation, a split from the successful underground psychedelic drag theatre group the Cockettes, which they believed had already become too slick. The Angels staged their free-wheeling extravaganzas in the street or donated spaces, giving them campy names like Last of the Red Hot Llamas, Tibetan Look of the Bed, and Peking on Acid.

Styling themselves as a haven for rebels and “freaks,” they proposed a model of theater as a way of life: the group insisted that members could not hold jobs and that all authorship had to be communal. “We wanted to start a new way of living that was not war-oriented or capitalist-oriented,” Tahara (aka James Windsor), a former member, recalls in an interview in the show’s excellent catalogue.

From the Angels of Light and Cockettes Photography Collection, circa 1970s.

Photo: courtesy of the Estate of Martin Wong and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

The smattering of snapshots of his Angels era at the Wattis capture the magnetism of this scene, replete with outrageous stunts including what appears to be a mock crucifixion and pansexual flower children, half-clothed or in drag. In one, a shaggy-haired performer, presumably an Angel, stands in the park in a costume that includes a Shiva-like bouquet of arms. He is observed from behind, as if from backstage, giving the image a lonely aftertaste.

Communing with the Angels while back in San Francisco from art school in Eureka, Wong participated as a designer of inventive sets using scavenged materials, but never as a performer. “We were group oriented, but he was his own entity within the group,” another Angel, Beaver Bauer, remembers in the catalogue. “I think he loved the Angels because through us he could work out a fantasy of the wild part of him—which he wanted, without fully committing himself to it.”

In 1974, Wong penned a postcard to the troupe, in his signature scrawl. It reads:

HELLO ANGELS HOW IS PARADICE. STILL STRANDED HERE ON EARTH AS USUAL, SLOWLY UNRAVELING LIKE A WEED IN SUMMER. FREIGHT TRAIN THUNDER ROLLIN PAST. JUST DOING TIME AS THEY SAY. WAITING FOR THE JUDGE. I LOVE YOU BUT I COULD NEVER BE A PART OF YOU. A MOMENTARY GLIMPSE IS ALL I ASK. DON’T DENY ME THAT. THE WAY IT IS IS THE WAY IT IS + THAT’S ALL THERE IS FOR NOW SEE YOU SOONER. LOVE.

So much in Wong’s stint with the Angels of Light is prescient about the artist that Wong would become. The line about being stranded on earth but with a glimpse of paradise might make you think, for instance, of Sweet ‘Enuff, with its gold-flecked heavens peeking out above the tenements.

Leaving California, Wong would scrap the colors of psychedelic San Francisco for the browns and greys of New York’s concrete-and-brick jungle. But he took from the experience his yen for seeking out inspiration among the overlooked, finding it among the graffiti kids and in the Nuyorican cultural scene in NYC, so thoroughly making this his world there that those who saw his paintings often assumed that he was a Hispanic New Yorker. Yet he also forever insisted that he felt himself to be a “tourist” here—a mental distance which gave him, I suspect, the freedom to meld its details with his own hermetic and dreamy symbolism. The paintings are gritty but also romantic, and difficult to pigeonhole; the formula for his art thereby echoes his path through life as someone committed to being an outsider among outsiders.

“Martin Wong: Painting Is Forbidden” is on view at the Wattis Institute, San Francisco, through April 18, 2015.