Art History

This Tender Mary Cassatt Painting of a Mother and Child Is Surprisingly Fraught. Here Are 3 Things You Might Not Know About ‘The Child’s Bath’

For Mother's Day, a look at one of the Impressionist's most celebrated.

For Mother's Day, a look at one of the Impressionist's most celebrated.

Katie White

When Mother’s Day was proposed as a holiday in 1913, American-French artist Mary Cassatt was not particularly keen on the idea. “As a staunch supporter of women’s suffrage, she thought granting women the right to vote was a far more pressing issue than a single day celebrating mother,” explained Kimberly A. Jones, curator of the National Gallery’s 2014 exhibition “Degas/Cassatt.”

The lack of enthusiasm might come as a surprise. Cassatt and motherhood are nearly synonymous in the public imagination —in her painted world babies and young children tenderly cling to their mothers, their tangles of hands and limbs becoming like one entity.

Detail of The Child’s Bath. Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Child’s Bath (1890), one of her most beloved paintings, encapsulates many of the nuances of Cassatt’s best work. A woman holds a small child on her lap as the child, a girl, dips her toes in a bowl of water, perhaps testing their temperature. The mother appears to be telling the child a story as she bathes her. Both tender and intimate, the image is also stylistically and technically innovative and full of surprises.

Ahead of Mother’s Day, we’ve found three insightful facts that just might change the way you see The Child’s Bath—and perhaps Cassatt’s work as a whole.

Correggio’s Madonna and Child with Sts. Jerome and Mary Magdalen (1528) was one of the paintings Cassatt was hired to copy by the bishop of Pittsburgh.

Cassatt’s depictions of mothers and children are often described as secular visions of the Madonna and Child—Cassatt scholar Nancy Mowll Mathews, for instance, described The Child’s Bath as resembling “Madonna washing the feet of the Christ Child.”

This was purposeful; as an upper-class woman artist in the late 19th-century, Cassatt was largely confined to depicting the domestic sphere—not the bustle of cafes and racetracks her male cohorts had access to. It benefitted Cassatt, therefore, to place her contemporary depictions of mothers and children in conversation with Renaissance religious scenes (Correggio, in particular, was an influence on the artist; early in Cassatt’s career she was commissioned by the bishop of Pittsburgh to travel to Parma and make copies of two Correggio paintings).

But these religious allusions and reference points had startlingly contemporary moral connotations, too. In France, the late 1800s were an era marked by an impassioned public fervor over disintegrating families among the working class and declining birth rates among the better off. The idea of the femme nouvelle was picking up steam in the public consciousness as women gained increased access to education, and by 1884, divorce. Many upper-class women, whose respectability was tied to their position as mothers within the patriarchal family system, felt their positions threatened by this dawning new womanhood—upper-class women who made up a devoted collector base for Cassatt, it might be added.

“If Cassatt’s presumably natural and spontaneous images of the mothers embraced by children who hang affectionately upon their necks remind us not only of Renaissance madonnas but also of the happy mothers of the 18th-century bourgeois art that too is not accidental,” explained art historian Norma Broude, “And as we now know such images were part of a wider… program of moral edification and reform that encouraged women to assume and indeed to wallow in the joys of maternal responsibility at a time when such behavior had not been the cultural norm.”

Considering the fact that Cassatt herself never married or had children and chose instead to pursue a career as an artist, her seeming embrace of these traditional values may seem antithetical—but the choice reveals the complex realities Cassatt and women of her time were navigating. Such idealized images of motherhood, Broude noted, offered Cassatt “one of the few, narrow gaps of possibility with which she, as an ambitious woman artist of the upper classes, could fully grasp and define for herself a socially acceptable professional status and identity.”

A detail of Mary Cassatt’s now destroyed Modern Woman mural (c.1893). Courtesy of Slide Gallery University of California, San Diego.

The same year that Mary Cassatt painted The Child’s Bath, she was commissioned to paint a mural depicting the “Modern Woman” for the annual World’s Columbian Exposition and Fair in Chicago. The mural would measure some 58 by 12 feet and occupy the tympanum of the entranceway to the exposition’s Women’s Building.

Cassatt divided the mural into three sections: Young Girls Pursuing Fame (left), Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge (center), and Arts, Music, Dancing (right). The imagery combined mythical scenes and biblical allusions (Eve and the apple) and art historical references into three scenes of women pursuing their goals. To Cassatt’s frustration, the mural drew sharp criticism, both for its modern style and the scene’s conspicuous absence of men—the largest central painting which depicted women passing down the fruits of knowledge to a younger generation particularly drew critical ire.

Mary Cassatt’s now destroyed Modern Woman mural (c.1893). Courtesy of Slide Gallery University of California, San Diego.

The artist wrote in a letter to a friend, “An American friend asked me in a rather huffy tone the other day, ‘Then this is woman apart from her relations to man!’ I told him it was. Men I have no doubt are painted in all their vigor on the walls of other buildings.”

A detail of Mary Cassatt’s now destroyed Modern Woman mural (c.1893). Courtesy of Slide Gallery University of California, San Diego.

The Child’s Bath can be read in concert with the Modern Woman mural of the same year. Unlike the multitude of Madonna and Child paintings throughout history which offered glimpses of intimacy between mother and son, traditionally most depictions of mothers and daughters had been painted as portraits, images constructed to be viewed by an audience. In Cassatt’s painting, instead, the mother and daughter appear absorbed in a world of their own and to which the viewer’s presence is not acknowledged.

Detail of The Child’s Bath (1893) by Mary Cassatt.

“Cassatt’s oeuvre … has figures who are oblivious to the outside world. These mothers and children, who depart from convention in their mutual absorption, challenge stereotypes because Cassatt acknowledges the strong emotions which are the human dynamics of the relationship,” wrote art historian Susan Fillin Yeh in her essay “Mary Cassatt’s Images of Women”

Detail of The Child’s Bath (1893) by Mary Cassatt.

What’s more, their bodies seem to mirror each other. Similarly, in the central panel of Modern Woman, one woman on a ladder passes a fruit down to a young girl, and their bodies echo each other. In The Child’s Bath, that physical mirroring happens between generations too. Both mother and child’s heads are tilted down toward the basin of water. As the mother seems to lightly squeeze the child’s right foot, the child mimics that pressure on its thigh, and as the mother wraps her arm onto the daughter’s right side, so too does the daughter grasp her mother, as though in unison.

Kitagawa Utamaro, Bathtime (Gyōzui) (circa 1801). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1890, Cassatt had seen a large exhibition of Japanese prints at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and would subsequently produce a series of lithographs inspired by these prints, including several scenes of bathing and mothers bathing children. The Child’s Bath most fully captures these influences with the figures popping against a flattened background.

It’s worth noting that ukiyo-e prints, too, captured a world of daily rituals and tasks—not of the upper-classes but of working-class performers, and courtesans—and in the world of courtesans, men too appear only as visitors.

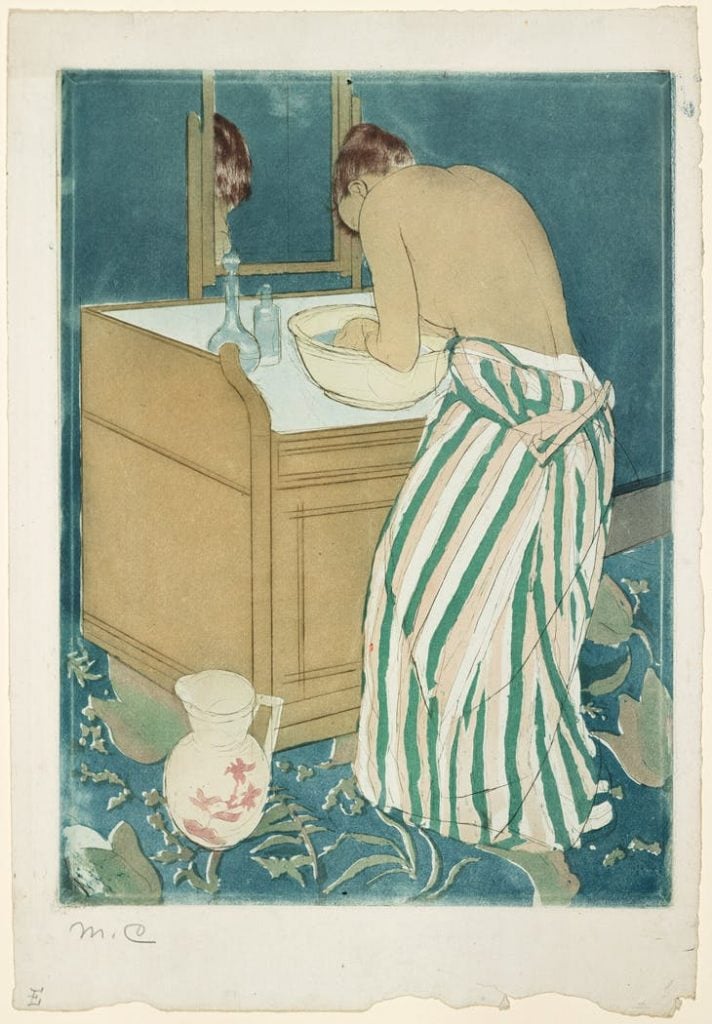

Mary Cassatt, Woman Bathing (1891). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Though faithful to the influence of Japanese prints, the quality of the drawing in the painting, seen so clearly in the child’s body, also alarmed some viewers, because of gendered beliefs in the nature of artistic ability. Charles Blanc, Beaux-Arts administrator and historian once remarked, “drawing is the masculine sex of art and color the feminine one.” As such, Cassatt’s strong graphic talents alarmed some viewers. Professor Paul Fisher noted that when the work first was shown in New York in 1895 one critic found the painting, “hard…crude…brutal…a shock to the eye.”

“Cassatt’s strong drawing….was not what a woman was supposed to be biologically capable of doing,” wrote Broude, “According to Cassatt’s own report Degas once said of her work that ‘no woman has a right to draw like that.'”