Art World

The Painter Mary Corse Is Having a Late-Career Market Moment. How She’s Handling It Offers 5 Lessons for Other Artists

Here's the secret to the artist's "50-year journey to becoming an overnight success."

Here's the secret to the artist's "50-year journey to becoming an overnight success."

Tim Schneider &

Eileen Kinsella

In today’s art world, we’re used to a certain kind of meteoric rise: a fresh-faced MFA student runs through a handful of gallery shows, signs with a market-making powerhouse, says goodbye to the people who helped them get there… and then, oftentimes, settles into a creative rut to meet demand for the work that made them famous, or crashes and burns because they flew too far, too fast.

Mary Corse is different. Since enrolling at the Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) in 1964, she toiled away for decades building a robust, diverse, and continually evolving practice investigating the limits of human perception. While it’s true that she received early institutional attention and has worked with gallerists since the mid-1970s, much of her support looks far more substantial on paper than it was in reality. She once noted, for instance, that Richard Bellamy, the influential but famously market-averse dealer who first showed her work, “liked his artist to suffer.”

In a previous interview, Corse emphasized that she “never saw art as a career,” and that she “always painted for [her] sanity.” Now, at age 73, the market is coming around to her regardless—and in a big way, as proven in this week’s news that Pace will represent her in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Seoul. Similar to the international arrangement announced between Corse and Lisson Gallery in London last year, Pace will work with her in collaboration with Los Angeles gallery Kayne Griffin Corcoran [where, full disclosure, artnet’s Tim Schneider previously worked as research director, giving him rich insight into Corse’s CV]. In concert with this trio, Lehmann Maupin,which has been working with the artist since 2011, continues to represent the artist in New York.

At the recent Art Basel fair, Lehmann Maupin sold Untitled (White, Black, Beveled), (2018), glass microspheres in acrylic on canvas, for $200,000 to a US museum trustee.

Not surprisingly, Corse’s commercial renaissance also dovetails with a flurry of high-level institutional activity. She is currently the subject of a career-spanning survey at the Whitney Museum (through November 25) and a solo exhibition on long-term view at Dia:Beacon, largely featuring historical works recently acquired by the foundation. The former show, titled “A Survey in Light,” will travel to LACMA after its run at the Whitney ends.

But why is all this happening now?

According to Pace senior director Elliot McDonald, the answer begins with the “broad reckoning in the art world—across galleries, museums, collectors, the public, et cetera—that for much of the last century the forces that shaped the appreciation and discourse around Modern and contemporary art paid far greater attention to Western male white artists, at the expense of everyone else.” That reckoning, he says, “has catalyzed a re-examination and invigorated appreciation for artists like Mary Corse, someone who has contributed as much to painting, our visual culture, and our understandings of subjective experience as any other artist of the last 50 years, yet for far too long went overlooked.”

Yet far more is involved, too, that speaks to the surprising rewards that reticence can bring an artist. In fact, a look back at Corse’s career shows multiple cases in which she has made the exact opposite choice that a market-driven artist would make—an encouraging trajectory for artists who hope that putting art first and playing the long game might sometimes pay off.

Indeed, artists and dealers alike may still be able to learn some things from Corse’s path. Here are five counterintuitive choices she made on her 50-year journey to becoming an overnight success that are starting to look very, very smart.

Installation view, Mary Corse, Dia: Beacon, Beacon, NY. © Mary Corse. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, NY. Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, NY.

“What’s important to understand about Mary,” says Bill Griffin, co-founder of Kayne Griffin Corcoran, “is that she never cared about conquering the art world. She just focused on painting, and she’s done whatever she needed to do to keep her studio practice moving forward, day-in, day-out, for over 50 years.”

This singular focus has shaped Corse’s life and work in very real ways. Instead of getting more deeply involved in the Los Angeles art scene then centered on Venice—the obvious move for any ambitious young talent at the outset of the 1970s—Corse moved to remote Topanga Canyon 48 years ago. The quiet and freedom she found there allowed her to drill into her practice with a singular focus. The environment was so suitable, in fact, that she has stayed on the same property ever since.

But it wasn’t easy. Corse endured many years of extreme financial hardship, especially as a single mother raising two boys. No doubt her choice to live outside LA’s social nexus contributed to the art world’s willingness to keep her in the background. Still, she stayed committed to Topanga for the greater creative good, even finding ways to safely hold onto several large early pieces that would have eased her burden significantly to leave behind or sell for huge discounts. Decades later, some of these same works form the bedrock of her exhibitions at Dia:Beacon and the Whitney.

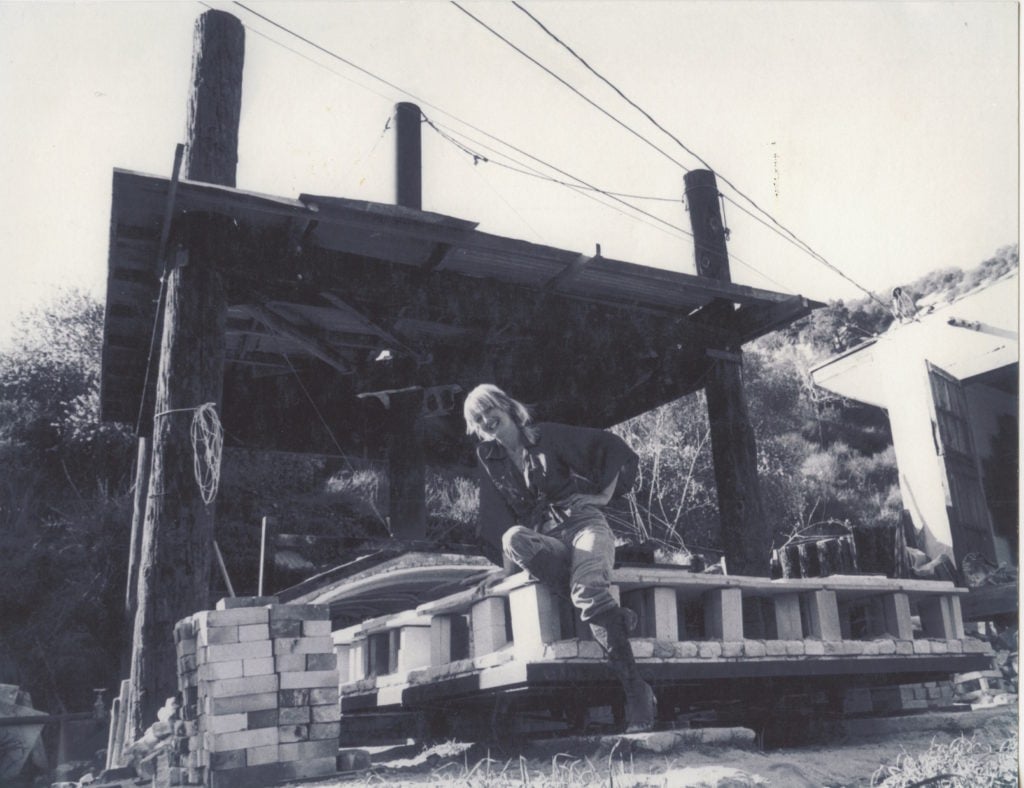

Mary Corse with the kiln built at her Topanga studio, ca. 1976. Courtesy of the artist, Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Lisson, London.

Although Corse is best known for her luminous White Light paintings, she consistently pursued ideas that evolved her central themes and diversified her practice in important ways. Usually, these ideas were riskier and more demanding than a short-term, market-based perspective would have allowed. Signal examples include her electric light works from 1966–68 (most of which were wirelessly powered by Tesla coils of her own design), the shimmering glazed-ceramic works she began in the 1970s (many of which were fired by Corse in an enormous kiln she constructed in her front yard), and the many monumental canvases (some as long as 34 feet) she has favored throughout her career—institutional sizes indulged even when she had little to no serious institutional support.

“Whether she was teaching herself physics to make her light boxes in the ’60s, or building a giant kiln that, by the way, every ‘expert’ in Southern California told her was impossible to build, or even making these epic-scale paintings when her bank account said she should be knocking out easily sellable, domestic ones instead, Mary has never been afraid to choose artistic progress over financial incentives,” says Griffin. This allowed her to deepen her approach to painting—which is how she categorizes her work, regardless of the materials used—and “consistently push the boundaries of painting, and the properties of light within painting, further and further in a ceaseless exploration of our subjective experience,” according to McDonald.

Mary Corse’s Untitled (Black Earth Series), 1978. ©Mary Corse. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York; courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

Corse certainly isn’t the first artist to prefer working with a constellation of galleries at different levels and in different regions rather than signing on with one or two blue-chip mega-galleries. But the decision does seem to get rarer every day. Corse’s approach speaks to an often-overlooked aspect of the poaching phenomenon: artists have a say in what happens with their galleries once the spotlight swings their way. There is no law dictating that they have to leave behind every representative who helped support them before the major museum shows and the multinational galleries came calling. If the relationships are strong enough, it’s still possible to work together on growth.

Mary Corse’s Untitled (Electric LIght), 1968/2018. ©Mary Corse. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York; courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

Other artists have played a significant role in Corse’s gallery relationships. Griffin, for instance, says he first became intrigued in Corse’s work after James Turrell, another gallery artist, told him that Corse was “the most underappreciated artist of their generation.”

Corse has also been attuned to the artistic context she would enter with prospective new galleries, and Pace’s deep history with her venerable peers like Robert Irwin, Donald Judd, and Robert Ryman proved alluring; Lisson, too, offered friendly common ground through its work with the likes of Sol LeWitt and Daniel Buren.

The admiration works both ways. McDonald cites Corse’s “fascination with perception and the role of light as both subject and object of art” as a common thread between her and the gallery’s Light and Space artists, headlined by Irwin, whom Pace has represented for over 50 years, and also significant painters like Agnes Martin, whose estate the gallery works with.

Entrusting her work to galleries that can provide such beneficial art-historical context could prove valuable over coming years, since curators at the galleries will find themselves tempted again and again to play up the connection between Corse’s art and that of her more famous and established coevals.

Mary Corse’s Untitled (White Light L-Corners, Beveled), 1969. © Mary Corse. Photo by Bill Jacobson Studio, New York; courtesy of Dia Art Foundation, New York.

Half a century ago, Corse was welcomed into the art world by some of the most prominent museums in the country. The Guggenheim, the Whitney, and LACMA all included Corse in exhibitions within three years of her graduation from Chouinard in 1968. All three institutions also acquired her work.

She saw some degree of early success with galleries, as well. Corse staged her first show with Bellamy in 1974. And while she showed even during the roughly 40 years between then and her 21st century re-emergence, every artist (and dealer) knows there is a difference between showing and being seen—let alone collected.

The secondary market helps tell this tale. According to the artnet Price Database, the highest price ever achieved at auction for a work by Corse is $312,500, paid for Untitled (White Light Grid), 1988, at Los Angeles Modern Auctions last month (June 18, 2018). In all, just 42 of her works have come on the auction block to date. Of these, 35 works, or 84 percent, were sold, but the vast majority of those sales took place during the many years Corse existed off the art world’s main stage.

As such, the prices previously distorted perceptions of her market. For example, Corse’s lowest auction price on record is just $999 for Untitled (in 6 Parts), 1988, a ceramic tile work that sold at Bonhams & Butterfields in 2004. In contrast, recent results on the primary market have been consistently robust. This year alone, Lisson reported selling works by Corse for $375,000 at Art Basel last month and $450,000 at TEFAF New York Spring, while Kayne Griffin Corcoran placed her 1991 painting Untitled (White Light Band) for $400,000 at Frieze New York.

“All the past auction results tell you about Mary is that people ignored her for decades,” says Griffin. “That’s even clearer today based on what you see happening in the world’s great museums and art markets outside the US. It’s really come full-circle for her.”

Pace’s presence in Asia has come full-circle, too. Noting that 2018 marks 10 years since the gallery opened its space in Beijing, McDonald sees Pace’s permanent presence in Hong Kong and Seoul as perfect homes for Corse’s practice. “We’ve seen tremendous and growing interest among collectors across the Asia Pacific Region in the work of pivotal modern and contemporary Western artists,” he says. “Having Mary Corse join the gallery is a tremendous honor, and we’re excited to shape provocative and nuanced dialogues between her work and the other major figures that shape Pace’s program.”

Still, even with all this newfound—and long-deserved—interest coalescing, one critical thing about Corse remains the same. “All she wants to do is get back to work,” says Griffin. Perhaps that’s the greatest lesson of all.