People

‘There Are Always More Questions’: Abstract Painter Mary Lovelace O’Neal on Creating Art That Refuses to Be Boxed In

In a career that spans decades, O'Neal has drawn strength from a powerful creative community.

In a career that spans decades, O'Neal has drawn strength from a powerful creative community.

Folasade Ologundudu

This article is part of a series of interviews by Folasade Ologundudu exploring the evolving conversation about abstract art among Black artists across different generations.

With a career spanning over 50 years, Mary Lovelace O’Neal has earned a place as one of the most serious abstract painters of her time. From her renowned “lampblack” paintings incorporating loose black powder pigment, to her large (and strikingly named) “Whales Fucking” series of the 1980s, O’Neal’s oeuvre has spanned artistic movements and moments—but always with a focus on the power of the abstract, and with ambition to spare.

Born in Jackson Mississippi in 1942, O’Neal’s father, Ariel O’Neal, was choir director and professor of music at Tougaloo College and the University of Arkansas. He played a critical role in her interest in the arts during her formative years.

Attending Howard University from 1960 to 1964, O’Neal studied under the now-legendary art historian and advocate David Driskell. During the height of the Civil Rights movement, with then-boyfriend Stokely Carmichael, she traveled throughout the U.S., participating in activism, joining in marches, protests, and voting drives.

In a distinguished career, she’s had solo shows at venues ranging from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in 1979, to New York’s Mnuchin Gallery, in 2020.

Over several conversations, I spoke with O’Neal about her life and work over the last half century and the legacy of teaching she’d like to leave behind for younger generations to come.

Can you describe moments in your life that initially led you towards becoming an artist and more specifically to working in abstraction?

There wasn’t an epiphany moment. Abstraction was natural to me. I wasn’t tapping into a movement. I always thought it was very natural and I didn’t understand why people didn’t see it the way I saw it. It was a natural way of responding to what I saw and what I felt about what I saw. Color was also always very important to me. I didn’t understand when my students were afraid of color.

Early in your career as an artist, what themes and ideas were you discussing and focusing on in your art? Are you still discussing some of those same themes in your current and recent work?

Yes, I have learned a lot from doing this work for 50-plus years. There are things that are no longer important to me and then there are other things that travel with me always.

What interests me are the things I can’t understand—sometimes these are even more important than the attempt to try to understand. Accepting this is what made my work work. There are always more questions—like how the fuck did I make that purple?

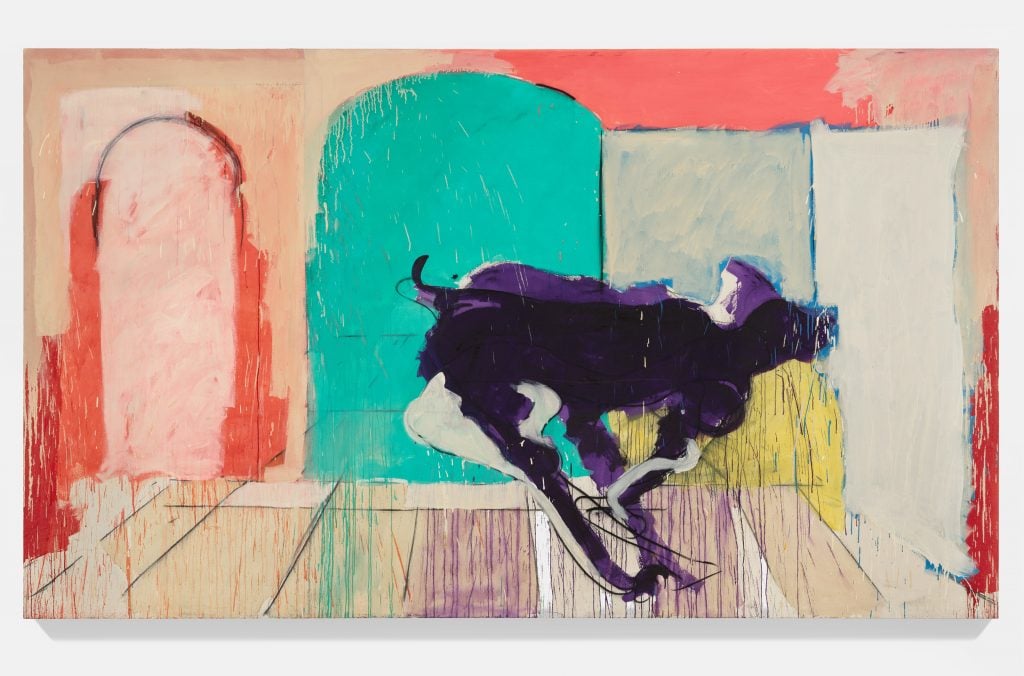

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Thelonius Searching Those Familiar Keys (1980s). (c) Mary Lovelace O’Neal. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery, New York, and Jenkins Johnson Gallery.

Community building and relationships are so important to an artist’s success. How did your social and educational relationships nurture and build your art career? Can you speak specifically about the people that had a lasting impact on you as an artist?

Well, most of them you wouldn’t know. My father was one. There was also a German artist at Tougaloo College who was involved in all that German Expressionism. He developed the collection at Tougaloo which was one of the best in the country at the time, Black or white, because they were given so many rare gifts from the 19th and 20th century and many pieces of African art. It was a huge collection. Unfortunately, that collection at one point was being sold off for pennies on the dollar. The administrators didn’t really know what they had and what they could have gotten for it. They only knew that it would keep the lights on.

I think that David Driskell remained a very, very important figure in the lives of all of us who were his offspring, the people who were at Howard when he was a very young professor. The wonderful thing about Dr. Driskell was that he never turned down a 3 a.m. call from any of us.

I had colleagues like [artist] Joe Overstreet. Anyone who was moving in and about Black art, if they were at Howard, I knew them and I worked with them. There was also my boyfriend, Stokely Carmichael, who used to come to my art classes. Driskell was very fond of him because he was so bright. And Toni Morrison.

My cultural life and my social life have been extraordinary. They are important to who I have become and important in terms of life in the 20th and into this 21st century—especially in terms of social movements having to do with African American history and culture.

I’ve had really valuable friendships, and not just with painters or visual artists but also with folks in theater. My first husband John O’Neal created the Free Southern Theater with Gilbert Moses, which was an incredibly important organ. Do you know what that is?

No.

This is something you have to know! Gilbert went on to do production in New York. And John did one-man shows throughout the country. I realize that a lot of you young people are going to white institutions where there is no place for that information, but you need to know.

I don’t mean to be pedantic, but I do mean to teach. I’m supposed to widen the path. It’s the responsibility of every African American person. I don’t care if you grew up in the middle of a cotton patch. You need to talk about that experience. Somebody needs to write it down, even if only you can do it. I am stunned again and again, just everyday, that I have seen so much. I am history. I’m a part of history. I’ve put my feet down and I have moved. I have footprints that go across generations, that go across decades, and I’ve been shaped and formed by that journey.

For the most part, my teaching has been in essentially white institutions. When I first started out, we were many, or so it seemed. By the time I left Berkeley, I was lucky to have one African-American student per year, either in the graduate or the undergraduate program, whether I was teaching painting or printmaking. It became very difficult. I actually began to pity the kids that I taught because they didn’t receive the kind of nurturing and the kind of interest that our teachers took in us [at Howard].

This went back to the idea of the Talented Tenth—it’s like we were being nurtured because we had a job to do. Whether we were clear about it or not, we were being formed and shaped to do that job.

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Running With Black Panthers and White Doves (c. 1989–90) (from “the Panthers in My Father’s Palace” series). Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of the Joyner/Giuffrida Collection. (c) Mary Lovelace O’Neal. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery, New York.

Talk to me about your experiences teaching. What was it like for you?

At the opening of a semester I would take my students to the local museums. I wouldn’t let them read those texts on the side of the work. I’d make them go through the whole show and give me a take on it that day without reading anything. That would be the first week. Midway through the class I’d ask them to go back and look at the work and write again about it.

Blackness itself is sometimes described as an abstraction. How do you view Blackness, not only as a color, but as a larger social and political concept? Does abstraction allow you to tap into ideas of Blackness through mark-making?

In terms of my art, the questions don’t really come from that kind of abstraction. My art comes from my observation of what’s around. The way I feel about abstraction and how I feel about me within abstraction at this point is really just so specifically mine. It’s not like I have this overwhelming interest in Abstract Expressionism; it just happens to be how I work. So often people try to lock me into that.

I think it’s so important to share that people have always tried to box you in to Abstract Expressionism. Can you speak more about some of those experiences?

I had come from Howard with a great interest in New York School painting. Even somebody quiet, like Rothko doing what he was doing—I was thrilled by that. I was also thrilled by what De Kooning was doing, which was in some ways a more natural fit for me.

But trying to lock me into Abstract Expressionism doesn’t work for me because that’s not who I am. I’ve got a lot of the energy of action painting. Maybe that’s a better fit for me.

People have always tried to box me in. There were also those people who kept saying, “You need to paint something about Black people,” which essentially meant Black women jumping out of the bush with machine guns.

If you look at what was happening in places like Cuba, Chile, and Italy, people were taking to the streets. In New York, Black artists were saying we want in, because what you are doing is keeping us out, not letting us make a living. These white boys couldn’t even deal with white women, it was just all about them. And so these young Black artists got out in the streets in front of the Whitney, in front of the MoMA, in front of the Met and said, “y’all got to give up some of this, baby, or we’re going to burn it down.” That’s the kind of energy that was there.

But I had a response to those people who were always on my back talking shit about what I wasn’t doing. I would say, look at the abstraction and the things that are not naturalistic that come out of Africa, and stop talking shit to me!

Mary Lovelace O’Neal, Forbidden Fruit (circa 1990s). Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging, courtesy of Mnuchin Gallery, New York.

In your opinion, will the work of Black abstract artists ever be as popular or deemed as important as the work of Black figurative artists?

It will be if people like you make it so. If you understand what’s going on with it.

Who are some of your favorite abstract artists and why? What artists do you look to as inspirations or precedents in your work?

I love De Kooning. I love Joe Overstreet. I love Sam Gilliam. I love, especially, Patricio Moreno Toro—you need to look him up. I think he’s one of the greatest painters. I love [Robert] Colescott. These influences don’t show up necessarily in the work itself, but they show up in the way I’m thinking about the work.

Some of these folks, I have personally spent sometimes half the night up with them, til three or four o’clock in the morning, drinking terrible whiskey out of cups that just contained turpentine, eating all kinds of really bad food. But talking and talking through the ideas. When you ask me about these relationships, they go deep.