Law & Politics

Massachusetts Attorney General Calls for a Temporary Restraining Order to Halt Berkshire Museum Sale

A judge will make a final decision on November 1.

A judge will make a final decision on November 1.

Eileen Kinsella

Opponents of the Berkshire Museum’s controversial planned sale have reason to celebrate.

Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey has recommended the court temporarily halt the auction of works from the museum’s collection so that she can have more time to study the sale and its legal ramifications. She appears to have been at least somewhat persuaded by Rockwell’s heirs and other museum donors, who argued in a lawsuit filed earlier this month that the sale is “unnecessary and unlawful.”

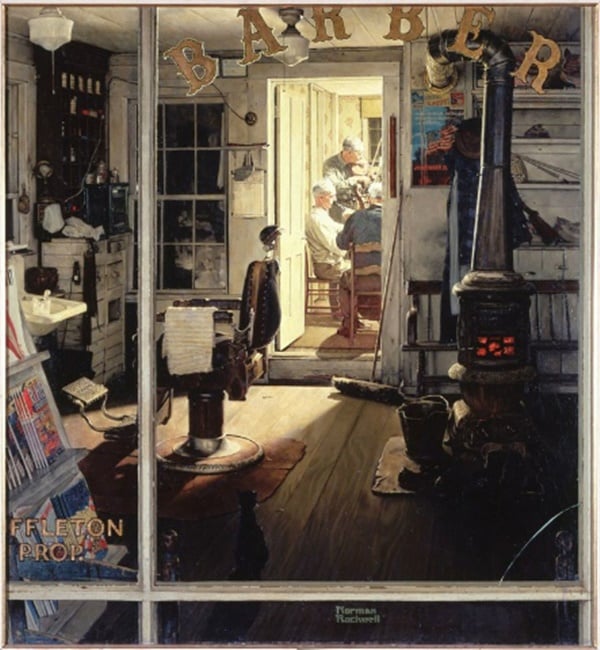

The first works are due to go under the hammer at Sotheby’s in just two weeks. They include a major Norman Rockwell painting, Shuffleton’s Barbershop, which has been estimated to sell for $20–30 million. The suit, filed by the artist’s heirs, is one of two that seek to stop the sale; a second suit, brought by a group of museum members, was filed last week. A judge in Berkshire County will make the final decision about whether to issue a temporary restraining order on Wednesday.

In the meantime, however, Sotheby’s and the Berkshire Museum appear unruffled and have no plans to change course. “We respect the role of the attorney general in this process, but continue to believe we have strong legal grounds to move forward and secure the future of the Berkshire Museum,” Elizabeth McGraw, the president of the Berkshire’s board of trustees, said in a statement.

A Sotheby’s spokeswoman added that the museum remains “fully committed” and will proceed with the sales, beginning November 13, “unless a court rules otherwise.”

In her 27-page ruling, issued this afternoon, the attorney general says a number of aspects of the museum’s plans raise concerns that would need to be resolved before any sale could take place. She notes that the museum was founded in 1903 by Zenas Crane as part of the Berkshire Athenaeum. As a result, it was subject to a restriction in the Athenaeum’s 1871 charter that no property, gifts, or bequests should ever be removed from Berkshire County.

To make matters more complicated, however, the museum separated from the Athenaeum in 1932—so there is considerable debate over whether the museum is still bound by that standard.

Norman Rockwell, Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1959). Courtesy Berkshire Fine Arts.

The Berkshire Museum has said that the sale of the artworks is necessary to keep financially afloat, to fund essential renovations of its 114-year-old building, and to rebrand itself as a mixed-use art and natural history museum. Its proposal has renewed a national debate over deaccessioning.

The attorney general’s report lays out the events that led up to the planned Sotheby’s sale. In 2015, the museum engaged a nonprofit consulting firm to help it tackle its financial challenges. It also asked Sotheby’s and Christie’s to value its collection, according to the ruling. In 2016, the museum’s board voted to enact a new business model and accepted the consulting firm’s recommendation to sell between 20 and 40 works.

Shortly after the board reached an agreement with Sotheby’s this summer, it voted to remove two key requirements from its collections management policy: one that stated that the museum must entertain acquisition offers from other institution before selling art privately, and another that specified that funds from the sale of art must be used for other acquisitions or the preservation of its collection.

Attorney general Healey cited the board’s decision to strike that language as part of her rationale for recommending the temporary restraining order. Healey also notes that Rockwell, who donated two of the works in question to the museum as gifts, “appears to have intended that his donations remain in the museum’s permanent collection.”

She says evidence suggests that the museum “understood at the time Rockwell donated the art that the pieces were his favorite oil paintings” and that his gift was motivated, at least in part, by a hope that they would remain on view in the Berkshires.

The ruling notes that the museum only informed the attorney general’s office of the planned sale “after the contract with Sotheby’s was executed.” The attorney general also found that “there is no indication that the museum is in immediate financial crisis, and the decision to promote and keep the November auction date was made despite… knowledge that the [attorney general] was still undertaking its review and had already identified potential barriers to the sale.”

William Lee of the firm WilmerHale, who is representing the Berkshire Museum, said in a statement that “we respectfully disagree there is any further inquiry for the attorney general to conduct before these long-scheduled sales can proceed.” He added that “we continue to believe there is no legal barrier to the museum proceeding with the deaccession.”