Art World

Meret Oppenheim’s Furry Teacup Stirred Up a Public Sensation—Here Are 3 Things You May Not Know About the Classic Surrealist Masterpiece ‘Object’

She spent years trying to escape its legend.

She spent years trying to escape its legend.

Katie White

Meret Oppenheim’s fur-lined porcelain teacup, Object (1936), made her an international art star.

Finding the mutant tableware both delightful and repulsive, Surrealist kingpin André Breton included Object in an exhibition of Surrealist objects at Paris’s Charles Ratton Gallery in 1936. Later that year, Object would head to New York for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism.” Of the 46 artists included in the exhibition, it was Oppenheim’s hirsute tea set that made the headlines—though they weren’t always particularly celebratory.

“The fur-lined cup and saucer with spoon thrown in for good measure gives an idea of all the goofiness started by the surrealist art exhibit in New York,” sniffed one critic. Nevertheless, the fame of the work grew so great that it nearly overwhelmed its creator. She felt the focus on the one sculpture overshadowed her larger artistic practice.

Mentally and emotionally depleted, the Swiss-German artist returned to Basel from Paris, spending more than a decade out of the artistic limelight (she destroyed many of the works she produced during that period, too). Though she intermittently displayed new creations with the Surrealists, Oppenheim would not truly return to the public eye until 1967, the year of her first retrospective in Stockholm, when she set about attempting to reclaim the narrative of her own career. (In a clever nod to Object’s outsized influence, she wittily produced a series of fabric “souvenirs” of the work in the 1970s.)

Today, Object is considered among the defining Surrealist sculptures. As the author and art historian Mary Ann Caws wrote, “It is an object par excellence both abject and project, given all the various sensual and psychological interpretations conferred upon it.”

Yet despite its fame, the work is still full of surprises. Here are three facts that might just change the way you see Meret Oppenheim’s Object.

Meret Oppenheim, Fur Bracelet. Courtesy of GEMS AND LADDERS.

Object’s Surrealist spin on a tea set began over coffee.

In 1936, the 22-year-old Oppenheim went to meet Pablo Picasso and his new lover, the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar, for lunch at Paris’s Café de Flore, a chic coffeehouse popular with the creative set.

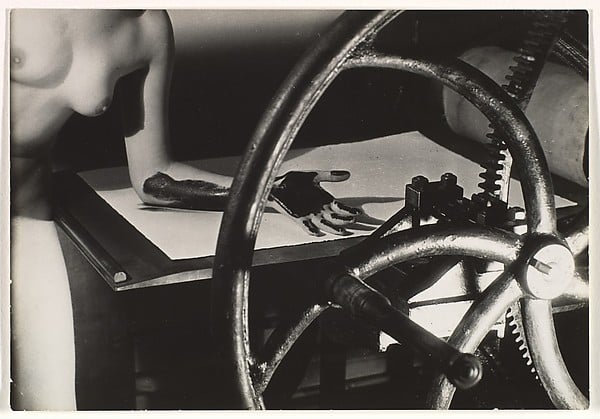

Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim at the Printing Wheel, 1933.

Photo via Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Oppenheim had already modeled for Man Ray a few years before, earning a reputation for her unique avant-garde fashion sense. She arrived at the café wearing an outlandish accessory: a thick cuff bracelet swathed in ocelot fur.

According to a much-repeated bit of lore, Picasso teased Oppenheim that anything could be covered in fur (in some versions of the story, this is a pubic hair joke). Playing along, Oppenheim quipped, “Even this cup and saucer. Waiter, a little more fur!”

The offhand exchange evolved into Object, with Oppenheim purchasing a white teacup, saucer, and spoon from a department store and wrapping them in the tan fur she supposed to be of a Chinese gazelle (conservationists haven’t agreed upon the material).

Meret Oppenheim, Fur Gloves (1936) at the artist’s retrospective at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius-Bau in 2013. Photo by John MacDougall/AFP via Getty Images.

Later in her life, Oppenheim would distance herself from “the artist who works in fur” label. But early in her career, she delighted in the material’s associations with untamed, female sexuality—as well as its suggestion of certain dream-like monsters. (Oppenheim was an avowed Jungian, even visiting Jung for analysis herself.)

In fact, even before that fateful Picasso/Maar meet-up, her interest in the relationship between textile and art grew when the young Oppenheim made several fashion accessory collaborations with famed Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli, the grand dame of Surrealist fashion crossovers (the lobster dresses and shoe hat she debuted with Dalí were another veritable sensation).

Woman’s Dinner Dress, a collaboration between Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The fur bracelet she’d worn to her lunch with Picasso had been designed for a collection with Schiaparelli the year before. In the months leading up to creating Object, she also designed fur-covered gloves with the fingertips snipped off and a fur-covered ring for Schiaparelli.

Meret Oppenheim, Object (1936). Image: Ben Davis.

Today, Object is among the Museum of Modern Art’s best-loved artworks, earning a central place in the museum’s recent reinstallation. Oppenheim has even been given the nickname the “First Lady of MoMA.” But she did not take a straight path to the museum.

“Few works of art in recent years have so captured the popular imagination,” founding MoMA director Alfred Barr remarked soon after the piece’s 1936 debut at MoMA’s Surrealist exhibition. “The ‘fur-lined tea set’ makes concretely real the most extreme, the most bizarre improbability. The tension and excitement caused by this object in the minds of tens of thousands of Americans have been expressed in rage, laughter, disgust, or delight.”

The museum’s board of directors was firmly in the “rage” and “disgust” camp. When Barr tried to add the work to the collection that same year, he was rejected outright. The board president scoffed at the work, deeming it among the exhibition’s “ridiculous objects.”

Undeterred, Barr personally purchased the work from Oppenheim. She wanted a thousand French francs; he counter-offered $50, about half the price, and the deal was sealed. (That’s a little more than $900 in today’s money, for reference.)

In 1940, Object was rejected once more by MoMA. Not until 1946 did Barr get his way, and even then, it came with a caveat: the work was added as part of the museum’s study collection, meaning it was rarely exhibited. Thus, during the time Oppenheim was trying to escape its fame in Europe, Object was languishing mostly out of view in the United States. In the early 1960s, it was reclassified and brought into the primary collection. The rest, as they say, is (art) history.