Art World

To Mark the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 150th Birthday, Here Are 15 Artworks Symbolizing the Ups and Downs of Each Decade of Its Storied Existence

From the Robber Baron era to the Global Tourism era.

From the Robber Baron era to the Global Tourism era.

Ben Davis

This Monday marked the 150th birthday of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It should have been a lavish celebration. Instead, of course, the museum lies lonesome.

Missed birthdays are a minor thing given the scope of world events right now. Still, it seems worthwhile to honor the occasion: the Met is the flagship of art history in the United States, and its own history says a lot about how the story of art has unfolded here.

So, I’ve combed through the compete list of exhibitions that the museum has hosted since its 1870 founding, picking out one work from each decade, either something unexpected and interesting, or something to illustrate how the museum’s identity has altered over time.

John Frederick Kensett, Twilight in the Cedars at Darien, Connecticut (1872). Image courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As far as I can tell, the very first solo show dedicated to an artist in the museum’s history was “The Last Summer’s Work of the late John F. Kensett,” held in March 1874. Which is emblematic, since Kensett was one of the founders and a trustee of the newly minted institution. Known as a “luminist” for his attention to the intricacies of atmosphere and light, Kensett was of the second generation of the Hudson River School. When he died in 1872 of pneumonia, the institution organized a tribute featuring the output of his final year of work, including this painting depicting a loose grove of trees simmering in the sunset.

Attributed to Pieter de Jode I, Neptune in his Chariot (late 16th–mid 17th century). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met’s programming in the 1880s was almost exclusively given over to exhibitions with thrilling titles like “Collection of Dutch and Flemish Paintings by Old Masters, Owned by Mr. Charles Sedelmeyer” and “The Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection in the New Western Galleries.” It was, in short, a place for the era’s super-rich to show off their cultivation to one another. This trifle, depicting a ferocious Neptune wielding his trident on his beasts of burden, was showcased in “The Vanderbilt Collection of Drawings in the East Galleries,” an ode to one of the most rapacious families of the Gilded Age, just a few short years after the Vanderbilt railroad empire was at the heart of one of the most brutal labor showdowns in US history, the Great Railway Strike of 1877.

Frederic Edwin Church, Heart of the Andes (1859). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frederic Edwin Church’s Heart of the Andes was the equivalent of IMAX entertainment of its day, going on tour and drawing lines when it debuted in 1859, with curious visitors scrutinizing its immense detail with opera glasses and paying 25 cents a pop to get a gander. Church died in 1900, and the Met played its role in lionizing American artistic heroism with the posthumous tribute “Paintings by Frederic E. Church,” including his famous showstopper.

Andrew Underhill, Tankard (ca. 1780–90). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The “Hudson-Fulton Celebration” is not much remembered today. It was a big deal back in the 20th century’s Oughts, as the city’s elite beat the drums for the New York’s surging commercial importance with a citywide commemoration of both explorer Henry Hudson and steamboat inventor Robert Fulton. A massive Carnival Parade took the streets, New York was lit up with electric light, and the Met pulled out the stops. It celebrated the city’s wealth both by showing off Old World cultural treasures—”Paintings by Old Dutch Masters (In Connection With the Hudson-Fulton Celebration)”—and by offering a patriotic exhibition making the case for the rising power’s own arts-and-crafts history, including a hefty selection of silver treasures from New York collections such as this lustrous tankard.

Katsushika Hokusai, Rooster, Hen and Chicken with Spiderwort (ca. 1830–33). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met did not, at this point, quite fit the profile of the omnipotent “encyclopedic” institution it is today. Aside from the treasures of the Old World, the other distinct cultural passion of its earliest era was the art of the world’s other rising industrial power: Japan, whose decorative arts and arms received much enthusiasm. Artist Francis Lathrop, a student of James Abbott McNeill Whistler and William Morris, was a keen collector of Japanese prints, and left his trove (including this glorious Hokusai) to the institution when he died in 1911. It was the subject of a showcase the following year.

An image of the San Francisco Ferry Building, the first picture sent over a telephone line from San Francisco to New York, using the variable width line process. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Roaring Twenties brought “Exhibition of Tele-Photographs Courtesy of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company” to the Met, an ode to the photo-electric cell, vacuum-tube amplifier, and electric filters that had made possible the magical transmission of images over long distances (aka “wirephoto”). “The fields in which electrically transmitted pictures may be of greatest service are those in which it is desired to transmit information which can be conveyed—or conveyed effectively—only by an appeal to vision,” speculated a pamphlet AT&T put out for the museum show, complete with diagrams of how the cutting-edge technology worked. “Examples of such cases are portraits, as, for instance, of criminals, or missing individuals, drawings such as details of mechanical parts, weather charts and military maps, and so on.” Other applications in advertising and news were mentioned.

Norman Lewis, The Wanderer (Johnny) (1933). © Estate of Norman Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

The Met’s program during the hardship years of the Great Depression seems mainly to have been business as usual—except for “Work of the Pupils in the New York City Free Adult Art Schools” in 1934, an exhibition sponsored by, among others, the government’s Relief Administration, with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as patron. The African-American painter Norman Lewis, who would go on to renown as an abstract artist, was then studying with Augusta Savage, the great Harlem sculptor and educator. Representing the Savage School at the Met’s show, his social realist The Wanderer (Johnny) won “special mention,” which helped make Lewis’s reputation. He also got $10, about $190 in today’s dollars.

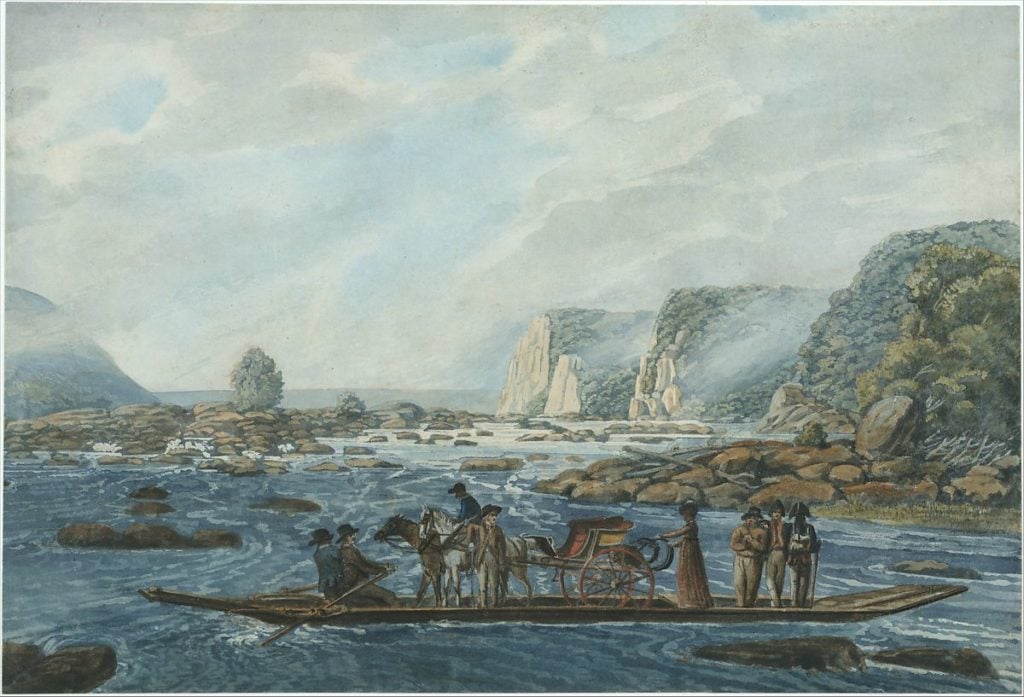

Pavel Petrovich Svinin, A Ferry Scene on the Susquehanna at Wright’s Ferry, near Havre de Grace (1811–ca. 1813). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During World War II, the Met’s programming steered towards patriotic fare like “American Industry at War,” “Work by Soldier-Artists,” “The War Against Japan,” and, in fall 1944, the immortal “Portrait of America, Organized by Artists for Victory, Inc. and Sponsored by the Pepsi-Cola Company.” Slightly more subtle in its propaganda thrust was the institution’s fresh focus on Russian culture: with Roosevelt’s 1941 alliance with Stalin, the US had to suddenly mentally change gears away from its prior anti-USSR fever. In 1942, the Met found a natural synthesis between the era’s patriotic Americana and its expedient Russophilia with “As Russia Saw Us 1811,” a show of images by Russian artist and adventurer Pavel Petrovich Svinin (1787–1839), depicting his travels in the newborn United States of America.

John Vanderlyn, Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles (1818–19). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The New York Times called this placid spectacle of imperial glory “one of the most extraordinary American works of art ever painted and, possibly, one of the largest.” And indeed it makes a fine symbol of the United States’s postwar conception of itself as displacing Europe as the new center of the world. The 156-foot walk-in painted view of the Gardens of Versailles by American classical painter John Vanderlyn (1779–1852) was installed permanently in the mid-’50s in a specially built circular room at the Met, where it remains an attraction today.

Lorenzo di Credi, Portrait of a Young Woman (ca. 1490–1500). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the signal events in the history of cultural diplomacy was the 1962-’63 US tour of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, hatched by First Lady Jackie Kennedy and French cultural minister André Malraux. It drew Beatles-level crowds in New York, with over one million people coming to get a glimpse of her enigmatic smile over the course of just three and a half weeks. “La Gioconda” was displayed in the Met’s Medieval Sculpture Hall. To make preparations for the intense interest in the show, the Met used its own, substantially less revered Renaissance painting, Lorenzo di Credi’s “damaged but evocative” Portrait of a Young Woman—a work from its collection inspired by Leonardo’s Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci—as a stand-in while they figured out how the crowd logistics would work.

The Temple of Dendur in the Sacker Wing as seen in the evening between two statues of Amenhotep III. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met’s ’70s programming is flecked with socially minded experiments alongside the usual feasts of treasures, including “… Because of an Emergency,” a show curated by Ann Marie Rousseau featuring photos by woman from New York women’s shelters, and something called the “Anti-Graffiti Art Poster Contest,” neither of which I can find any information about. But the main story was that the age of blockbuster programming arrived in earnest with “Treasures of Tutankhamun” in 1978–79, still the Met’s second-most-attended show, which even spawned a hit Steve Martin novelty single. The show’s arrival at the Met coincided with the opening of its Temple of Dendur. Its a Roman-period artifact completed in 10 BCE and thus separated from King Tut’s time by about 13 centuries—about as far apart as we are today from the fall of the Roman Empire. Still, it was the perfect prop to capitalize on the big museum’s enduring association with mass-culture “Egyptomania.”

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes (1888). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Vincent van Gogh was the art star of the Reagan Era. His romantic mythos was a palette cleanser amid all that Wall Street yuppie excess, while also backstopping the era’s turn to florid Expressionism in art, and becoming one of the most massive symbols of art excess himself, as prices for his paintings scaled the heights of cautionary hubris at auction. The Met was a player in the global furore, offering back-to-back Van Gogh exhibitions, “Van Gogh in Arles” in 1984, which featured these rugged peasant shoes, and “Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers” in 1986–87.

Onésipe Aguado de las Marismas, Woman Seen from the Back (ca. 1862). Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met has collected photos since 1928, but it was late to break out a standalone photography department or to dedicate special photography galleries: both happened in ’92. Its early photography collection was greatly enhanced by selections from the storied holdings of the Gilman Paper Company, first shown in “The Waking Dream: Photography’s First Century” in 1993, which included this wonderfully enigmatic print by French viscount and photo enthusiast Onésipe Aguado de las Marismas. (The Met acquired the whole Gilman Paper Company Collection in 2005.)

Cai Guo-Qiang, Clear Sky Black Cloud (2006) on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Met’s rooftop commissions have been one place where it tested out embracing new art. If there was a big symbolic inflection point in this program, it would probably be Cai Guo-Qiang’s 2006 commission, which featured a previously alien-to-the-Met level of zany theatricality, including giant crocodiles, fake dead birds, and the detonation of a cloud of black smoke in the skies above the museum. Roberta Smith deemed the latter “explosion-performance” a damp squib, but still thought that “the very transience of this work is a radically new sculptural concept for the Met.” In anointing a Chinese artist (albeit one with an HQ in NYC), it also marked the Met’s turn away from playing to a specifically America-centric taste—previous commissions tended to come from well-established US heroes like Roy Lichtenstein and Sol LeWitt—and toward the “global contemporary art” tastes of the New Gilded Age.

Alexander McQueen, Jacket: It’s a Jungle Out There (autumn/winter 1997–98) in “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” at the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute. Photo by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images.

The Costume Institute has been part of the Met since the ’40s and won buzz in the ’70s for shows like “The World of Balenciaga.” But in the 2010s, the tail of fashion really began to wag the dog of the art museum. Images of the Met as a stuffy temple of connoisseurship were definitively displaced in the media hive mind by paparazzi shots of the red carpet of the Met Gala (and celebrities smoking in the Met bathroom). The big harbinger of all this was the mega-success of 2011’s “Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty,” the Andrew Bolton-curated ode to the rockstar designer that attracted legions and became a pop-culture phenomenon. With the Costume Institute as the key lure, the Met kept setting attendance records in the 2010s, led by Costume Institute shows including “China: Through the Looking Glass,” “Manus x Machina,” and “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.” Only a full-on Michelangelo survey in 2018 could break fashion’s streak as the main eyeball-getter for the 21st-century Met.