Art World

Here Are 10 Amazing Secrets About the Metropolitan Museum of Art, From Its Florist-in-Residence to Its Hippo Mascot

Discover the greatest little-known facts about the famous museum.

Discover the greatest little-known facts about the famous museum.

Katie White

“Its scope is mind-boggling. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is a repository for more than two million art objects created over the course of 5,000 years,” wrote Michael Gross in Rogue’s Gallery his sensational and highly readable history of the US’s largest museum.

The museum looms large in the cultural imagination too: cinematic hits like Manhattan, The Thomas Crown Affair, and When Harry Met Sally all filmed scenes in its storied halls. But even a museum so well known holds a few secrets—from financial up-and-downs to sculptural chicanery.

For instance, until Wangechi Mutu’s new humanoid sculptures were installed in the niches on the museum’s facade just this week, very few people realized those spaces had lain empty for more than 100 years simply because the museum had run out of funding.

So before your next cocktail party, test your Met Museum knowledge, with this list of little-known facts.

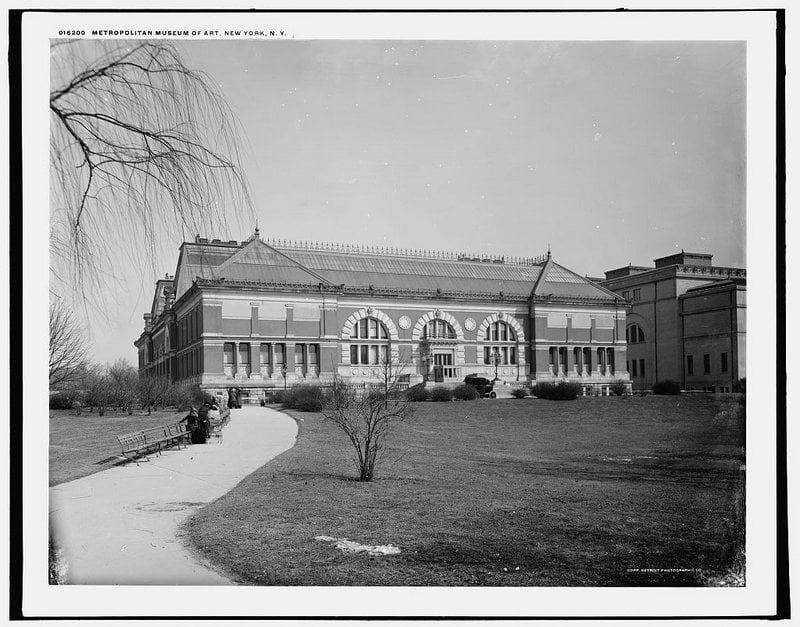

Metropolitan Museum of Art (1893). Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Now synonymous with its sprawling digs on Fifth Avenue, the Met didn’t actually get its start there. The museum was incorporated in 1870 by a group of forward-thinking financiers, philanthropists, and art enthusiasts, and opened two years later in a comparatively diminutive building at 681 Fifth Avenue. There it housed fewer than 200 European paintings and its first acquisition—a Roman sarcophagus that is still on view. But the collection grew while the building did not and the museum then briefly resided in the Douglas Mansion estate on West 14th Street until its Fifth Avenue home was completed in 1879.

The Robert Lehman Wing is one of the few places where visitors can see the museum’s original red-brick facade. Courtesy of Flickr.

In 1880, 10 years after it was incorporated, the museum opened its doors at its current location on Fifth Avenue and Central Park. But the building today would be unrecognizable. The Ruskian Gothic original was designed by Calvert Vaux (a designer of Central Park) and Jacob Wrey Mould and characterized by its red-brick facade. Expansions began soon after the building was completed, however (the earliest beginning as soon as 1888), and today almost all of the original structure has been encompassed by expansions. but for those eager to see a glimpse of what was, the west facade of the original building is still visible in the Robert Lehman Wing.

It’s also important to note that the Fifth Avenue of the 1880s was far from the hoity-toity Upper East Side that it is today. Instead it was considered a kind of cultural nowheres-ville, surrounded by farmland and far from the gilded mansions of downtown. In The Age of Innocence, the consummate New York sophisticate Edith Wharton describes the remote museum as “mouldered in unvisited loneliness.”

A terracotta zoomorphic askos (vessel) with antlers. Middle Cypriot III, ca. 1725–1600 BC. The Cesnola Collection. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During his years as the US consul to Cyprus during the 1860s to 1870s, the grandstanding eccentric Luigi Palma di Cesnola acquired what was thought of as the superlative collection of Cypriot art and objects, numbering at approximately 35,000. In the mid-1870s, Cesnola agreed to sell the collection to the fledgling Met for $60,000… and a catch. Along with the purchase, Cesnola demanded to be named the museum’s first director, a post he held from 1870 until his death, in 1904.

Cesnola’s thirst for the limelight had other, more art-historically relevant consequences. In turned out that Cesnola had gone about melding arms, legs, torsos, and other fragments of disparate sculptures to create a rather imaginative Frankensteins of Cypriot. He’d also told his fair share of mistruths about where he’d acquired his works.

For years after his tenure, the museum found itself uncertain of the appropriate path to take and his collection languished in storage. That is until 2000, when the museum faced the facts and put almost 600 works from his collection on view with didactics that told the truth of Cesnola’s inventive, fabulist creations.

Courtesy of Van Vliet & Trap.

The art is what’s meant to keep our attention, but sometimes visitors should stop and smell the roses (or whatever flowers are in the jaw-dropping bouquets) in the Great Hall of the Met. First things first: these towering floral displays are most certainly real and, since 2003, the hand behind these living still lifes is none-other than the Met’s in-house resident florist, Remco van Vliet.

The Dutch-born florist was born into the trade generations ago: His great-grandfather was part of Holland’s famed floral industry and his father and grandfather ran a booming floral business called Den Helder, which saw the likes of Queen Beatrix as regular clients. Now Van Vliet spends his weeks arranging the centerpiece museum goers all know and come to expect—the 10- to 12-foot-tall arrangement that anchors the lobby’s information desk. He also builds the bouquets on view from the nearby sandstone alcoves. Van Vliet has said that his arrangements are often inspired by the museum’s art works.

Oh, and another fun fact: those flower pots? They were endowed by Lila Acheson Wallace, the heir to the Readers Digest fortune, in 1970, who wished visitors to be greeted by fresh flowers.

This is not the actual TSA-approved screening facility at the Met, which we imagine is way more high-tech. Courtesy of Mark Kolbe/Getty Images.

Transportation Security Administration agents rifling through a museum’s carefully packed artworks is the stuff of a registrar’s nightmare. But it was one that could very easily have become a reality. Back in 2009, Homeland Security mandated anything shipped as cargo on a commercial flight would be open to search by the TSA. To give an idea of the art-shipped scope, a New York Times article from 2010 estimated that almost 20 percent of art is crated this way.

And while human safety is first priority, the idea of TSA agents scooping out packing peanuts, shifting tightly arranged pallets, and man-handling priceless antiquities and artworks was too much for the museum to bear. The Met, along with other mammoth institutions including MoMA, the Getty, and the National Museum, all enrolled in a federal screening program that allows them to operate secure screening facilities within their own buildings and thereby minimize the re-screening of their works.

A new book Stealing the Show by the Met’s former head of security tells the tales of many a robbery, both botched and successful. Courtesy of Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

The digital age has brought many changes to the art world, among them a sharp uptick in security capabilities. Until recent decades, museums including the Met wrestled between allowing the public fairly uninhibited viewing experiences and maintaining adequate measures of safe-keeping. Oftentimes, unfortunately, would-be thieves came out winning. In 1979, a 23-pound marble sculpture of the Greek god Hermes from the fifth century, valued at $150,000, was pulled from a wooden pedestal. Soon after it was reported stolen, its whereabouts were called in—but with the mysterious addition of a heart carved onto its visage. This and other tales of thievery are recounted in Stealing the Show, a recently released book written by John Barelli, the Met’s chief security officer until 2016.

The gardens of the Cloisters are filled with plants documented in Medieval times. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As many visitors know, the Met sprawls beyond its Fifth Avenue location. It also encompasses the Cloisters in Fort Tyron park in northern Manhattan, and (for the time being) the Met Breuer, on 75th Street and Madison. Visitors to the Cloisters will be pleased to discover three gardens (each planted in 1938, the year it opened) based on Medieval gardening traditions. Among these the Bonnefont Cloister garden will especially appeal to any millennial witches out there—it runneth over with nearly 300 species of plant, many of which were used in Medieval times, for magic, as well as medicine, food, and artistic purposes. You’re not allowed to touch, but keep your eyes open for such potent plants as Deadly Nightshade.

The 81st Street entrance to the Met is a sure-fire time saver that hardly anybody uses. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Undoubtedly one of the great pleasures of the museum’s stunning lobby, known as the Great Hall, but waiting in interminable lines of tourist throngs at the main entrance is not what most of us would deem an enjoyable experience. What insiders know is that the best entrance to avoid the masses is at 81st Street (before the stairs) at the Uris Center for Education Entrance. This is also the spot to go for accessibility. Here you’ll find shorter lines, a gift shop, less-frequented bathrooms, and elevators that will bring you to the Great Hall with your tickets already in hand.

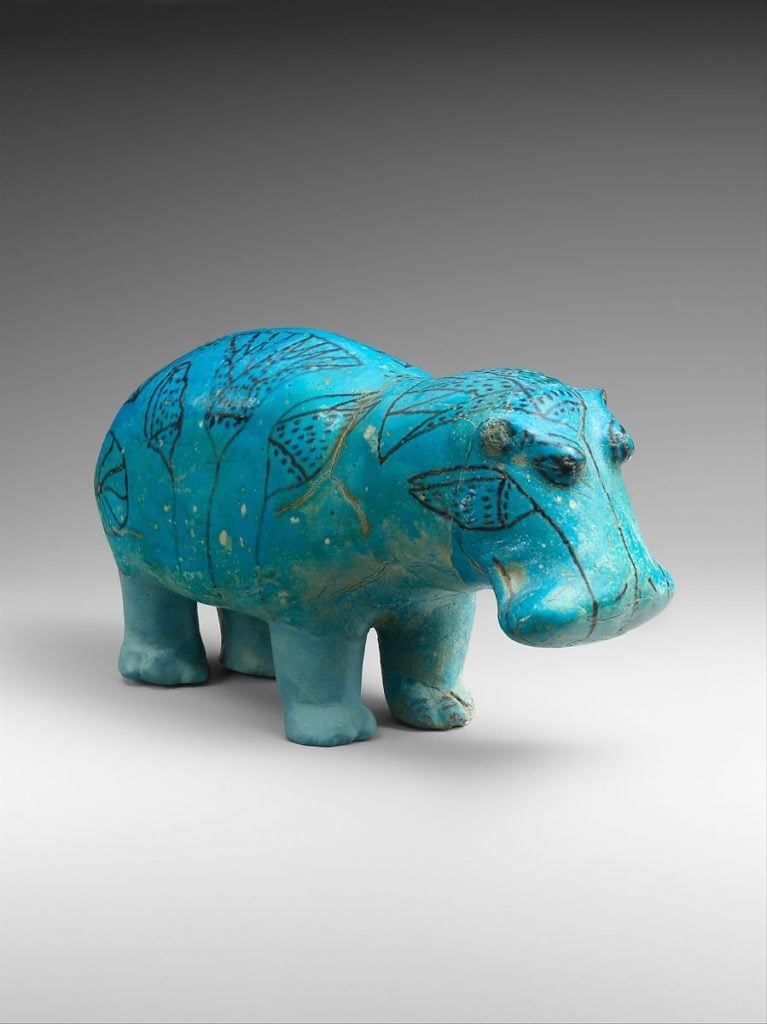

Hippopotamus (“William”), ca. 1961–1878 B.C. Courtesy of The Metropoliatan Museum of Art.

Though this blue statuette of a hippopotamus is undeniably adorable, for ancient Egyptians the gargantuan creature was a real threat even in the afterlife, liable to trample fisherman in the marshes of the Nile or those on the journey in the afterlife. This blue-glazed lotus-decorated little guy was found in the outer-workings of a tomb in Upper Egypt with three of its legs broken (now repaired), likely a measure to keep it from harming the deceased in the afterlife. William garnered his nickname in a 1931 humor magazine, which referred to him as an oracle. Ever since, he’s been the museum’s mascot of sorts—which has got us wondering about the mascots of other museums in the city…

For nine days, Indian artist Nikhil Chopra will perform a range of various personae as he interacts with objects in The Met collection. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum. Photgraph by Stephanie Berger.

Now here’s a first: The Met’s 2019–2020 artist in residence Nikhil Chopra will be taking that title very literally for nine days this month. From September 12 to September 20, the artist will be living in the museum, in the longest durational performance piece he’s done to date. Titled Lands, Waters, Skies, Chopra’s performance will be a nomadic itinerary of his own creation throughout the museum. He’ll be venturing through the Temple of Dendur, the Medieval Sculpture Hall, and the Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing #370 installation, among other stops, and inhabiting a sweeping range of costumed characters and personae as he does so, even playing music on the way.

We know what you’re wondering: Yes, he’ll be sleeping in the museum too. While we’re not sure where Chopra will be catching his winks, we can only hope it’s in one of the museum’s more lavish period rooms.