Art World

A Dishy New Novel Imagines the Backstage Battles at the Met’s Annual Temple of Dendur Dinner. Read an Excerpt Here

"Metropolitan Stories" author Christine Coulson worked at the Met for 25 years.

"Metropolitan Stories" author Christine Coulson worked at the Met for 25 years.

Christine Coulson

They were known as Mezz Girls. Everyone swore that the young women of Development’s mezzanine offices were indistinguishable, one from the next.

That night, before the party, they were being trained.

It was still the Age of Socialites, a post–Bonfire of the Vanities, pre-celebrity era. A pageant of rich women with hard hair and important jewelry. Black-tie meant gowns that rustled as they swept across the Great Hall. It was the sound of expense.

The guests were due to arrive in thirty minutes, so the Mezz Girls listened carefully as Winny Watson’s instructions hummed and rolled like those of a ballet teacher.

“Arms parallel, palms to the sky, and turn,” she said. “Aaand again. Arms parallel, palms to the sky, and turn.”

Winny, a museum volunteer and former Mezz Girl herself, insisted on this awkward movement as a graceful way of directing people without pointing. The maneuver began with elbows clamped to the waist, forearms positioned as if preparing to receive a heavy box. The “turn” signaled a swing of the upper body, torso twisting in the desired direction.

The Mezz Girls followed along, exchanging skeptical glances.

“What the fuck?” one snorted. The Mezz Girls liked to swear, but only amongst themselves.

Winny continued to issue instructions in her Park Avenue caw, wearing a one-shouldered gown that revealed ripples of loose flesh over her fit tennis arms. While her authority over matters like pointing had questionable origins, her Mayflower pedigree did not. She descended from Eatons on her mother’s side and Fullers on her father’s, creating a gene pool as shallow as a serving of consommé at the Colony Club—with a worldview to match.

The Mezz Girls were all pleased when the first tottering guest appeared in the Met’s doorway, abruptly halting the lesson.

“Thank fucking God,” they sang in unison.

When the partygoers entered the museum that evening, a miniature graveyard greeted them: a long table spread with hundreds of perfectly spaced envelopes the size of business cards, alphabetically arranged—one for each guest—and set atop a dark linen tablecloth. The pristine white rectangles rested on their half-opened flaps, a name carefully calligraphed on the front and a table number tucked within. It looked like Arlington National Cemetery for mice.

The curious sight of this tabletop graveyard was coupled with a ritual. The well-dressed Mezz Girls snapped up the correct card for each person entering the museum, efficiently—though not hurriedly— presenting it to them: “Good evening, Mrs. Astor. May I give you your seating card?”

As the rush of arrivals quickened, the swinging rhythm of card retrieval and distribution accelerated, growing almost competitive among the jostling Mezz Girls, with the ultimate goal of clearing the table. When an unknown guest had to retrieve their own card, the shortfall crushed the young women. Success meant the obliteration of the entire cemetery—a resurrection of sorts—as each guest thwarted the fate of the miniature tombstone. But some cards inevitably remained until the end of the evening. Sullen memento mori to those who never arrived.

’m bored. This is boring. Are you bored?” They all heard Mrs. Leonard Havering address this question to no one in particular. Her defining impatience had amplified with old age, a slow lacquering built with fine layers of loneliness. She had just entered the Great Hall and was anxiously scanning the room as if searching for a missing cat.

“Oh dear, you know these evenings take a bit of time to pick up steam,” the wise Mrs. Wilmington counseled after catching the remark. She delivered her comments as if waving away a slow, buzzing fly. “I hear the auction is unrivaled this year, so sip some champagne and get your bidding arm ready.”

All this came from Mrs. Wilmington’s mouth while she continued to move right past Mrs. Havering to avoid the risk of an actual conversation. Had Mrs. Wilmington simply flown away, it would have had equal effect.

The preppy wife of one of the museum’s Trustees charged toward Mrs. Havering like an overgrown Girl Scout. Mrs. Towey never appeared quite right in a gown; even at the age of sixty-seven she looked like a star field hockey player on awards night, hair clipped with a single barrette at her temple, constantly adjusting the long strap of her evening bag like it was a backpack filled with books.

She cartoonishly kissed her own palm and then pushed her hand on Mrs. Havering’s cheek with an exaggerated shove. The slap-kiss. It was her trademark. Mrs. Havering bristled, but the Mezz Girls enjoyed Mrs. Towey’s unfiltered energy.

“Great to see you!” Mrs. Towey barked. “Another show here at the rodeo! Ha! Great! Bye!” She tackled her next victim before Mrs. Havering could even respond.

Everyone seemed to be moving but Mrs. Havering. She had somehow stranded herself on a rock as the social stream whirled around her. Her eyes skipped around the room, and she absentmindedly touched her hand to her chest and felt for the lavish sapphire necklace that spread across her gown. It reminded her of her wealth, quietly clarifying that she belonged in this crowd so clearly repelled by her presence.

In these moments, the Mezz Girls could tell that Mrs. Havering missed her late husband. They missed him, too. Leonard was the fun one, the gregarious foil to her hard edge. Over the years, his cupcake optimism grew into a glittery persona, drawing everyone into his jolly parade of banter and delight. “I’m just glad you’re playing for our team!” he would cheer to the Mezz Girls as they took his coat or gave him his seating. “You’ll be running this place soon!” They loved his attention, his bold trespass across the usual silence, if only for its recognition that they actually mattered in some small way.

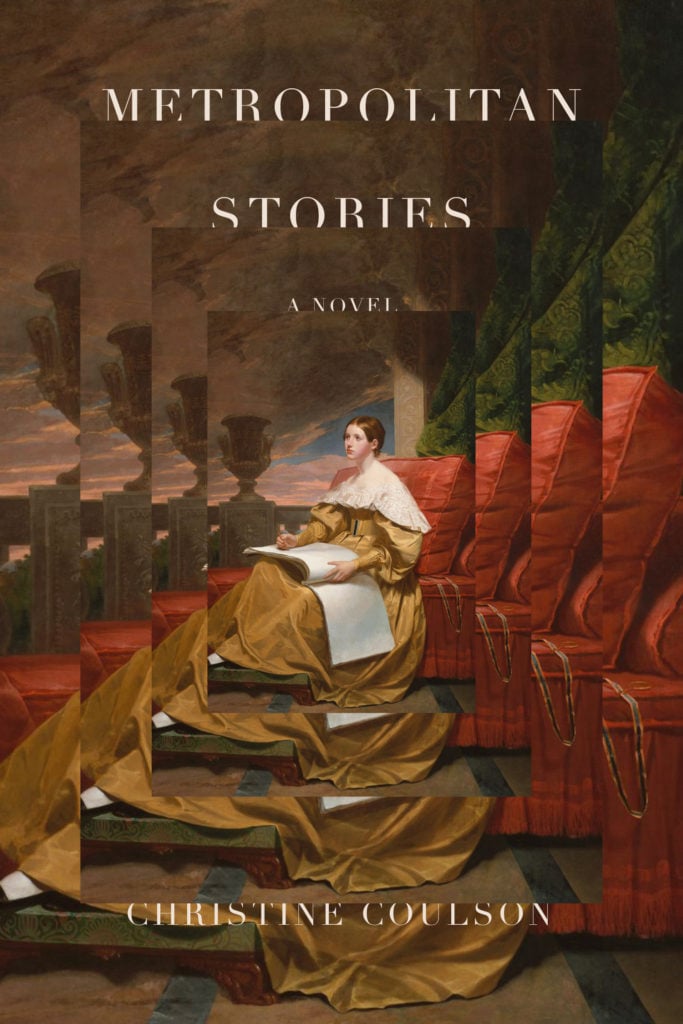

The cover of Christine Coulson’s Metropolitan Stories (2019). Courtesy of Other Press.

“Mrs. Havering!” Lindie Garrison approached the small, smirking woman with a waving enthusiasm that betrayed her ambition.

The Mezz Girls knew that Lindie’s infamy sprouted last year when she held a dinner party for thirty people and the waiters left midway through the meal. In her careful instructions to the caterer, she had neglected to sign the overtime clause. When the chef took too long preparing the halibut au gratin, the staff simply walked out at the hour they had been told.

The dinner party ended with a wine-soaked Mr. Garrison earnestly singing “Blowin’ in the Wind” to their guests as he sat on the edge of the couple’s bed with his acoustic guitar.

It would be a limping return for young Lindie. “Lindie,” Mrs. Havering replied with a neutrality that Lindie read as progress. “I would love

to catch up, but I see someone from the Greek and Roman Department whom I must speak to about a sarcophagus.”

At that very moment, a rose fell from one of the oversized floral arrangements in the four niches of the Great Hall; Lindie saw it and pouted, perhaps recognizing the possibility of a similar fate for herself.

One of the Mezz Girls also noticed the fallen flower and retrieved it with a swift, boomerang movement, scooping up the wayward rose and returning to her post like a ball girl on a tennis court. The Development Office trained its own like ninja. A Mezz Girl could sail across a room, airborne, to retrieve a dropped fork before it hit the ground. Legend had it that one of their ranks supported a broken elevator from below—a high-heeled Atlas to the elevator’s sky—when the Emperor of Japan was briefly trapped inside.

Met style—a cocktail of European elegance and Protestant restraint—had rules, imperatives that defined every element of an evening, from the personalized seating distribution to the silent commandeering of a chair for an elderly Trustee, complete with a museum curator to keep her company. A stray, dead flower would not do.

Cocktails continued in the Great Hall, as furred and feathered couples gathered around the Information Desk, now transformed into a circular bar with waiters serving from within its perimeter. The lights were dimmed, and hundreds of votive candles spread across the steps of the grand staircase, conjuring a private night sky for the great and the good who now populated the Hall’s cavernous space: men and women, middle-aged and older, puffed with the sort of lucky birth or financial achievement that inevitably led to big rooms filled with small chairs fashioned from gilded bamboo. The Met had convened its club, and this benefit to raise money for building the collection felt like its annual dance.

When Mrs. Wrightsman passed through the entrance, it was as if the Mezz Girls heard a dog whistle. They reflexively locked their eyes on her and smoothed their dresses. The collector of all collectors, donor of all donors, queen of all queens. Like royalty, Mrs.

Wrightsman didn’t need attention, rather, she was to be protected from it.

The Mezz Girls watched with the restraint of a silent army as Met Director Michel Larousse bounded to the door for the museum’s most important Trustee. She spoke in a porcelain voice that matched her fragile silhouette and went straight to business.

“Michel, I walked in with Danny Swillbinger and encouraged him about giving his collection,” she said confidentially about the well-known collector of Fragonard drawings.

She then paused and added with a sly humor, “Just so you know I’m still pushing the firm.”

“Indeed, you’re our own prized pit bull,” Michel smiled as he lightly took hold of her arm. He swam in her attention, relieved by her presence. It meant he could neglect everyone else.

A gong rang through the Great Hall. Again, the Mezz Girls snapped into action, springing from one troupe to the next to ask politely that they move in to dinner. Daphne, a Development veteran, approached a group near the Roman Galleries with a mild but deliberate force.

“Excuse me. If you could proceed to the Temple of Dendur for dinner now…” She tried Winny’s patented upper-body shift to point in the direction of the Egyptian Wing, but felt like a Barbie with back problems.

Mrs. Randolph ignored Daphne’s instructions, turned to her, and asked in her syrupy drawl, “Well what do you think, young lady? Who’s the better artist, Picasso or Braque? Jim here thinks ol’ Pablo was just a better salesman.”

Daphne hesitated, rattled by the interaction, but then responded earnestly, “Isn’t the most interesting period for both artists the moment when you can’t tell their work apart? When they are side by side developing Cubism, and the work is indistinguishable?”

Mrs. Randolph raised an eyebrow and paused as Daphne panicked that she had overstepped. “I like you!” Mrs. Randolph replied brightly. “You’re smart, and you’re decorative.” She appraised Daphne in her blue dress, then picked at it approvingly as if she were removing lint.

The ancient Temple of Dendur sat like a nightclub on the Nile, dazzling and radiant in the slippery reflections of the water that surrounded it. On the platform around the Temple, thirty-two tables ached under piles of flowers, porcelain, glass, and silverware. A piano sent an endless song into the air.

One of the Mezz Girls, who had trained as an archaeologist, wondered what anyone would make of a society represented by such mass-produced excess, a society with ritual public sacrifices in the form of fundraising auctions. She looked down at the pamphlet that sat at each place. She had heard about this year’s special packages, designed to encourage the men to bid.

Many of the Mezz Girls were in the meeting when Mrs. Barnley, the evening’s formidable Chairwoman, declared that “men are the new women” for any successful charity auction. The evening’s offerings seemed to represent her best guess at what that meant.

THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART ACQUISITIONS BENEFIT AUCTION

October 4, 1999

The Lance-a-Lot Package

Grab a weapon and suit up in full armor for a Central Park joust that everyone will enjoy. All equipment courtesy of the Arms & Armor Department. Commemorative video included.

Guns!

Horses not your thing? There are other Arms to explore. How about a few rounds in the Museum’s basement shooting range? You can keep the paper targets and brag about your blow holes.

Die Like an Egyptian

Jar up Uncle Miltie’s favorite snacks and send him smiling into the afterlife. The Egyptian Department technicians know all the ancient secrets of preservation. Let them deliver what no modern funeral can with the ultimate in personal care.

Row, Row, Row Your Boat

Whip by those other boats in the Central Park lake with a canoe from the African Galleries. It’s all the adventure of world travel, right here in our backyard.

The Mezz Girls watched Mrs. Havering approach her table, scowling. They also noticed the strange man with elaborate facial hair who stood next to her seat as if waiting for her. He had a thick gray beard along the sides of his face and a walrus-like mustache, with what appeared to be a two-inch wide landing strip shaved up his neck to his lower lip. It made his chin look like a tiny, naked ass bending over to expose itself beneath a hairy dress.

“Look who’s here, ladies,” one of the Mezz Girls said, “Everyone’s favorite asshole.” They were used to the ghost of Jacob Rogers showing up at these events to taunt and tease the guests.

“Old Havering’s gonna meet her match tonight,” Daphne responded, her eyes fixed on Rogers.

All the Mezz Girls knew Rogers. The locomotive magnate had been kicking around the Met since he died in 1901. Back then, he shocked the museum by leaving it his entire fortune. The six-milliondollar gift was a lottery boon, and the museum went shopping. Van Goghs and Bruegels and Greek vases, masterpieces by the thousand. The Met was still spending it.

But Rogers was also a legendary jerk, called “a pure animal man” in his own obituary. He often showed up at the museum’s black-tie dinners like an embarrassing uncle at Thanksgiving. And as with any family, all the Mezz Girls could do was try to limit the damage.

“I don’t like anyone I don’t know,” Mrs. Havering cracked by way of introduction as she sat down. “Indeed,” Rogers replied with admirable gentility and a hint of agreement, as he instinctively pulled out her chair.

“I’ve lived too long and done too much to have to spend an evening with some stranger,” she continued, now shouting upward as he remained standing.

Rogers’s thick wool dinner jacket looked like a dusty theater costume, and she inspected it with a questioning glare. She also noticed the shifting quality of his presence, at once overwhelming and not quite there, and attributed its elusive character to the dramatic lighting that had been designed for the evening. Spotlights shot asymmetrically across the room, striping the Temple in their path and pooling in bright circles upon the gallery floor.

“I could not agree more, madam.” Rogers’s curt accommodation merely fueled her rage.

“I tell you, a single woman in this town gets treated like the help. I get shoved with any nobody they can find.”

Rogers was unflinching; Mrs. Havering had indeed met her match. “No more than an unattached gentleman, I assure you. We have solidarity in that.”

Mrs. Havering smirked and started her cat search again, rolling her eyes around the room with skittish speed.

“Why do I even bother coming to these things,” she grumbled. The list of auction items lay on her plate, and she reviewed it with her lips tightened in tense disapproval.

“This place has lost all its dignity,” she muttered— again, with no intended audience.

The Mezz Girls wondered if Mrs. Havering couldn’t benefit from a joust or a few rounds in that firing range. Wealth could be a burden in New York if you joined the wrong game: So many rituals were required to distribute your money and stay relevant. But jumping on a horse and poking the innards out of someone at full speed, or shredding a target with a violent spray of well-shot ammo….Ah, the release that might deliver for her pent-up anger and resentment.

Mrs. Havering didn’t seem to notice that the rest of the guests at her table had arrived. Two fortunate no-shows bracketed her and Rogers, isolating them from the six guests on the other side of the table. The Mezz Girls wondered if they should find fillers, but knew it was a boulder of an assignment for even the most genteel diplomat.

“Fuck it,” they decided. Mrs. Havering’s table would be closely monitored instead.

Rogers and Mrs. Havering spent the first course of the meal in an epic silence, as she continued to sway back and forth, bobbing and weaving in her seat, sizing up the other tables to identify everyone else’s more favorable placement. Even Lindie Garrison had been placed next to a curator from the Asian Department.

Sliced cucumbers held the first course’s salmon mousse topped with caviar. Rogers scraped off the mousse to eat it, then lifted the cucumber pieces to his mouth, scooping them up awkwardly with his knife and fork. His knife slipped while conducting this odd operation and a large cucumber disk careened through the air. A Mezz Girl intercepted it with the stealth flash of an outstretched arm, just as it was about to peck at the back of an expansive helmet of hair. One small seed escaped, stuck in the net of hairsprayed tendrils, hanging tenuously like a spider from its web.

After the first course, the auction got underway, helmed by a Christie’s auctioneer who knew almost everyone there. Rumor had it that he had drawings of every Upper East Side residence that might one day have property to sell—inventories and scribbled notes sketched on cocktail napkins in cramped powder rooms during dinner parties and receptions, tracking each home’s future potential as a source of revenue.

He dove quickly into the first item, the Lance-a-Lot Package, which drew bids at a steady clip, easily reaching $750,000. The momentum slacked as the price neared $1 million. Unfazed, the auctioneer shifted gears and began to promote the package’s commemorative video. He pointed to the flickering projections playing behind him on the wall: old black-and white films of museum staff dressed in armor from the collection as they jousted in Central Park.

“In the early years of the twentieth century, Trustee Edward Harkness used his Hollywood connections to get a movie camera for the Met’s Egyptian Expedition,” the auctioneer explained, “In the off-season, the camera returned to New York, and, as you can see, the staff got a little creative.

“This is once-in-a-lifetime stuff, people. Do I hear $1 million?” he added.

“One hundred and twelve million!” Rogers called out impatiently, with an old-fashioned stiffness that just narrowly veered from a British accent. With his formal intonation, he sounded like an overeager amateur on stage.

The Mezz Girls rolled their eyes.

“Now he’s fucking with the auction,” one of them hissed.

“I bet that amount is what his original gift would be worth now,” another one added, shaking her head and folding her arms across her chest.

Mrs. Havering pivoted dramatically toward her neighbor. Her eyes widened with shock, as if she had finally found the cat she had been hunting for all night, only to discover that it had a hundred and twelve million dollars. Leaning back in his chair, Rogers moved into one of the streams of light and now seemed like a reflection in a cloudy mirror. She could have pushed her hand right through him.

Murmurs rippled through the stunned party, and the bewildered auctioneer dropped the hammer without so much as a countdown, anxious to lock in the bid.

“Sold for one hundred and twelve million dollars to the very generous gentlemen at table twenty-three!” he shouted.

Hesitant, confused applause broke out, and immediately a fuming Mezz Girl appeared at Rogers’s shoulder, knowing that she had to keep up the charade of his antics.

“Your name, sir?” she asked politely, her pen poised above her clipboard.

The crowd hushed with a prying quiet—the leaning curiosity of the rich—interrupted only by the scrape of chairs turning toward the man’s table, waiting for his response.

“Jacob S. Rogers,” he proclaimed, then paused for effect, “of Rose Lawn, Paterson, New Jersey.”

“Paterson, New Jersey??” Mrs. Havering exclaimed into the silence, now doubly slighted by being seated next to someone from New Jersey. “No one is from Paterson, New Jersey! ”

Confusion gripped the room. Some had heard of Jacob Rogers and began to whisper questions in a real-time gossip chain. The chatter swelled and grew louder.

Enjoying the disorder, and the fury he had inspired among the Mezz Girls, Rogers stood up from his chair, stroked both sides of his substantial beard, and crossed the room. The guests quieted as they watched him move through the tables.

After descending the few stairs from the Temple platform, he walked straight through the gallery wall, dissolving into a cloud of shimmering dust. The Mezz Girls heard him snicker as he left.

“Bastard,” they muttered.

The crowd exploded again with more questions.

“Typical!” Mrs. Havering howled from her perch, now fully exasperated. She craned her neck and scanned her table incredulously; the cat was lost again.

Then she twitched, and her face suddenly softened. She registered the strangeness of Rogers’s appearance and disappearance: If Rogers was a ghost, then maybe her husband, Leonard, could be in the room, too?

Her eyebrows curved into gentle arches framing a new depth in her eyes. Her stern, pursed lips relaxed into an expression of hope and expectation. She brightened, sitting upright like a young woman in her gilded chair, as if waiting for someone to ask her to dance. She gazed around the room again, but this time breathless, her heart quickening with the idea that Leonard could be near.

When Leonard Havering rested his hand on his wife’s shoulder, all of her indignation and anger fell away. She gasped and floated upward to him, relieved, renewed.

The Haverings swayed together within the commotion of the rustling crowd, a waltz of memory and comfort. A tent of light formed a cone of glittering dust just for them, as they moved within a bright circle upon the floor. Leonard glowed as Rogers had, ethereal and indefinably vague, while Mrs. Havering clutched the back of his dinner jacket with childlike fists, a desperate attempt to keep him.

“I don’t like anyone I don’t know,” Mrs. Havering whispered, this time a confession rather than a complaint. She buried her head in Leonard’s chest and finally spoke the truth, “I think you’re the only person I’ve ever really known.”

He smiled—that blooming, optimistic beam that always sliced through her despair—and pulled her closer. “I know,” he soothed, his voice as clear as water, her face lifted to the past, “I know.”

Over at Michel’s table, Mrs. Wrightsman sat serenely, enchanted by the Haverings and the gentle chaos Rogers had stirred. In the raking light, she looked just like the Met’s marble head of Athena, goddess of wisdom, from the late second century BC— bought with the Rogers Fund in 1912.