Art World

At 88, Mexican Surrealist Pedro Friedeberg Has Seen It All

The living legend and inventor of the hand chair chats about Leonora Carrington, Mexico City in the 1940s, and tequila.

It was already a surreal experience waiting for the 88-year-old artist Pedro Friedeberg. It was October, and the Tribeca member’s club had only been open a few months, but its rustic interior design, peacock wallpaper, and faux ivy made it seem like it was a vestige from another era. The artist was also ostensibly here to discuss tequila. But for the moment no one could find him.

Friedeberg came bounding up and said, “There are games downstairs! Scrabble, something called ‘Ladders and Snakes’ or ‘Serpents and Ladders.’ Old games from the 1920s. We were playing something called Sorry. It’s very childish.”

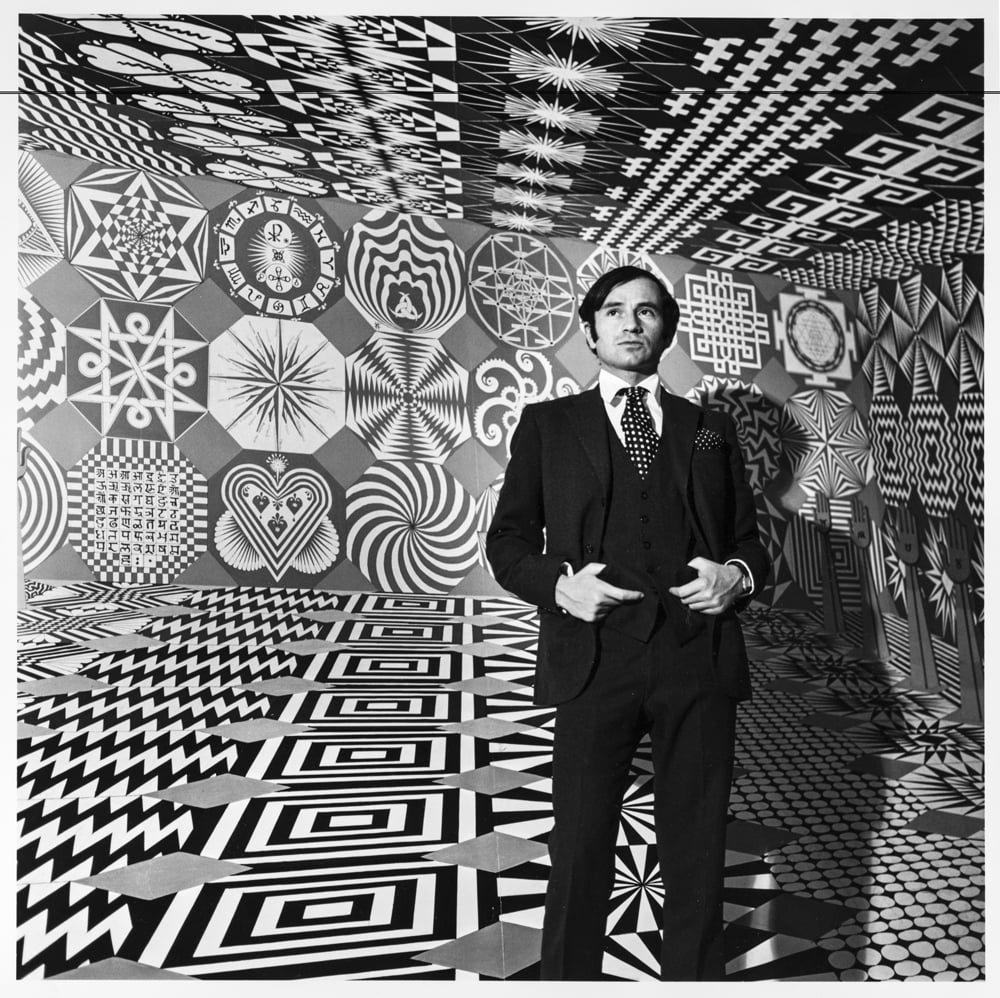

Pedro Friedeberg and his 1800 Milenio Artist Series x Pedro Friedeberg bottle. Courtesy of 1800 Tequila.

The summer heat had carried over to autumn, but Friedeberg looked dapper and resplendent in a gray pinstripe suit and royal blue shirt. He sat down on an overstuffed sofa. In front of him on the coffee table was a vase of flowers—some of the blooms were spray-painted silver. Next to it was the Milenio Artist Series limited-edition bottle of 1800 Tequila Friedeberg designed (only 1,800 have been created). “Tequila is a very Mexican drink,” Friedeberg said. “It’s now become popular all over the world. Especially in the States also. This is aged in French cognac casks. It’s a nice bottle. If it was smaller, it could be Chanel perfume.”

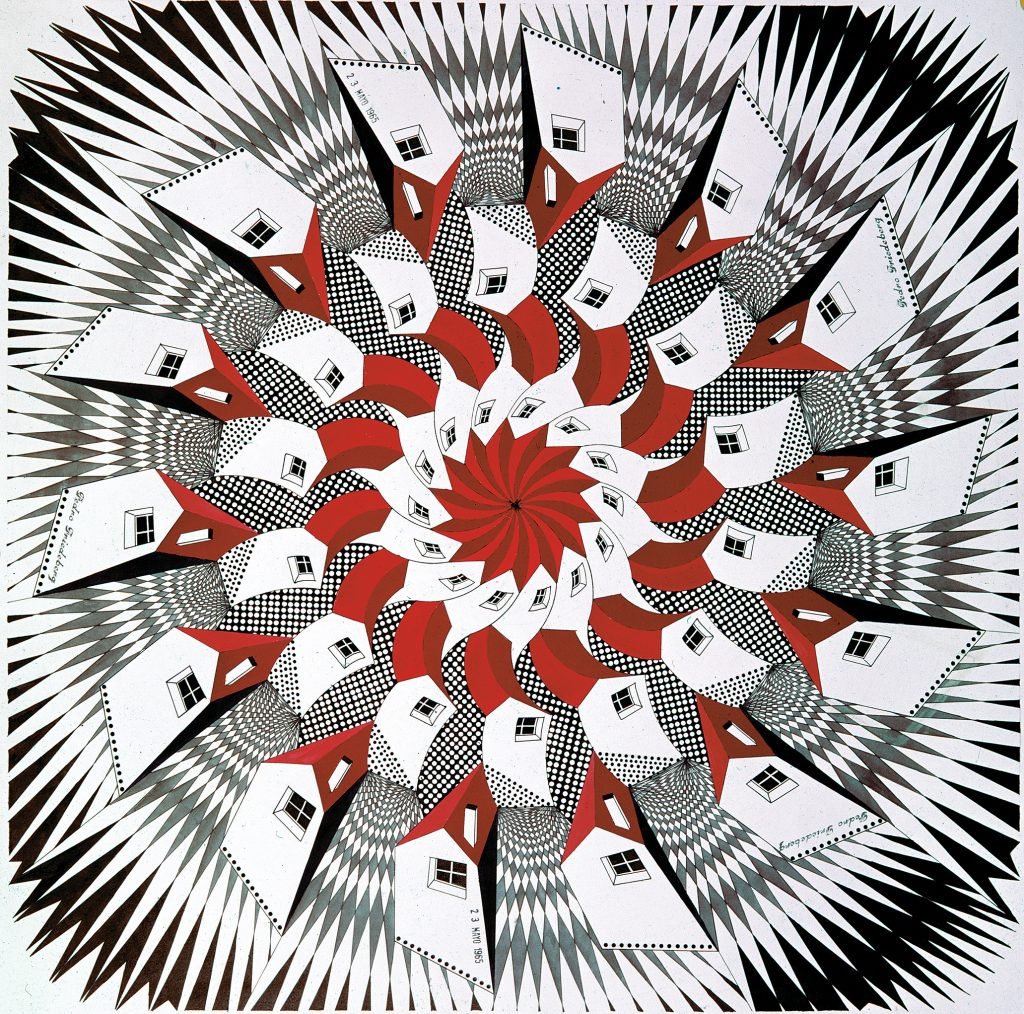

Pedro Friedeberg, Orfanatorio Para Tehuanas (1968). Courtesy of the artist.

Friedeberg is perhaps best known as the inventor of the much-copied hand chair in 1962. He originally trained as an architect, and his decades-long art practice incorporates intricate visual coding, complex symbology, and esoterism. He currently has an exhibition up at the Casa Chihuahua museum as well as a small show in the gallery of the Mexican consulate in New York. An art book will be released later this year. He has no plans to slow down.

He succinctly sums his bio up in an artist statement: “”I was born in Italy during the era of Mussolini, who made all trains run on time. Immediately thereafter, I moved to México where the trains are never on time, but where once they start moving, they pass pyramids.”

Pedro Friedeberg, Silla Dorada. Courtesy of the artist.

Friedeberg is the last living Surrealist of the Mexican contingent of European expats that included Remedios Varo, Wolfgang Paalen, and Leonora Carrington. “Leonora was like a very bourgeois English lady,” Friedeberg said. “Very correctly dressed, but very crazy at the same time with two very crazy children. The two boys inherited her house, and they made a big mess of it because they fought. They were fighting always. Now they’re old. They must be 60 years old by now. They’re also in Colonia Roma, very close to where I live. All the Surrealists lived around there. Varo, Carrington, Sofia Bassi. All lady painters who if they were alive now, they would be millionaires. They’re selling for so much more than before.”

Friedeberg landed in Mexico City well before it was the epicenter of the art world. “I arrived when I was three years old in 1939,” he said. “Imagine. There were still street cars instead of buses. There were very few cars. There were only like a million and a half people and now there’s like 20 million living in the whole Valley of Mexico. I have a very good memory of what streets looked like. There were no skyscrapers. They built one skyscraper, which fell down in an earthquake.”

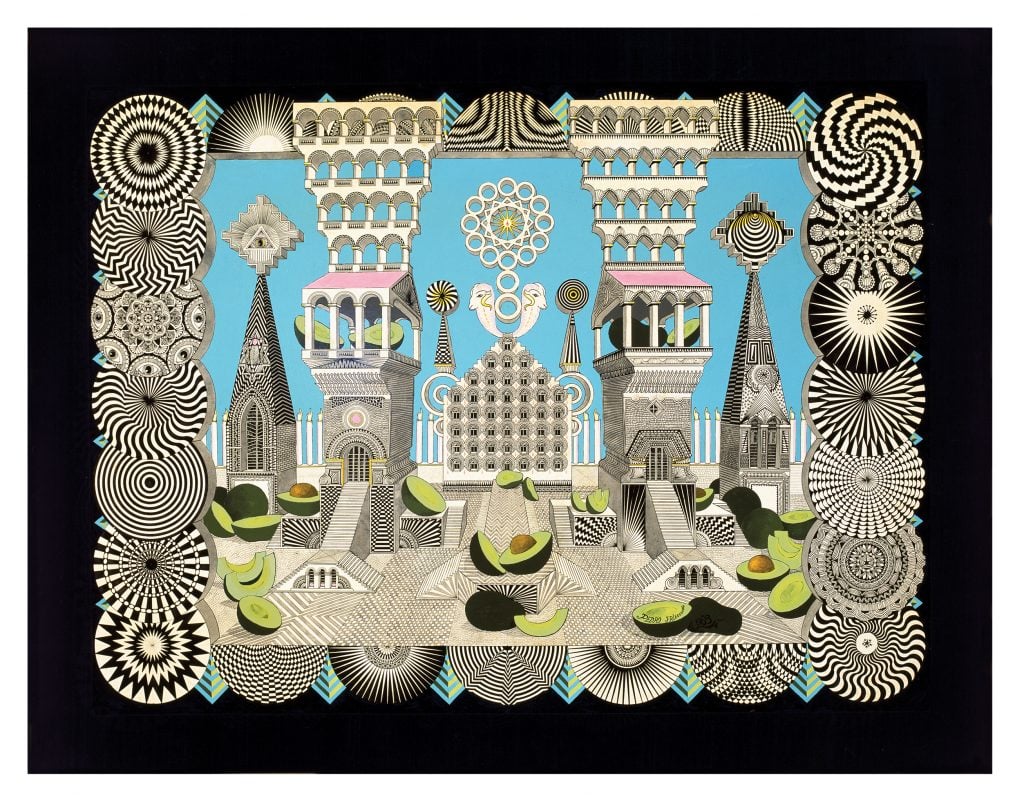

Pedro Friedeberg, Palacio de La Gioconda Durante la Semana de la Mona Lisa (1963). Courtesy of the artist.

It must be hard not to be nostalgic when he walks the streets and remembers them throughout the decades. “Well, it was like a totally different place,” he said. “It was also very dirty. Now it’s somewhat cleaner. People are more careful. People now stop for a red light. There were a lot of accidents all the time. People were always crashing into each other.”

I ask about something that doesn’t exist about life there anymore. “When I first got there, I lived with my grandmother,” he said. “She was living there since 1911. In those days, everybody had a lot of servants, and she had a cook, and they cooked on charcoal. You went down the street there was a man who sold charcoal. You put them in the bottom of the stove and you poured some kind of liquid over it, it was like petroleum or something, and then you lit a match to it and then you cook your beans on top. And you had to fan it all the time so that it couldn’t go out. It took hours to cook something. You left it overnight, but it tasted much better because it cooked for so long in a clay pot. That’s one of the things I miss.”

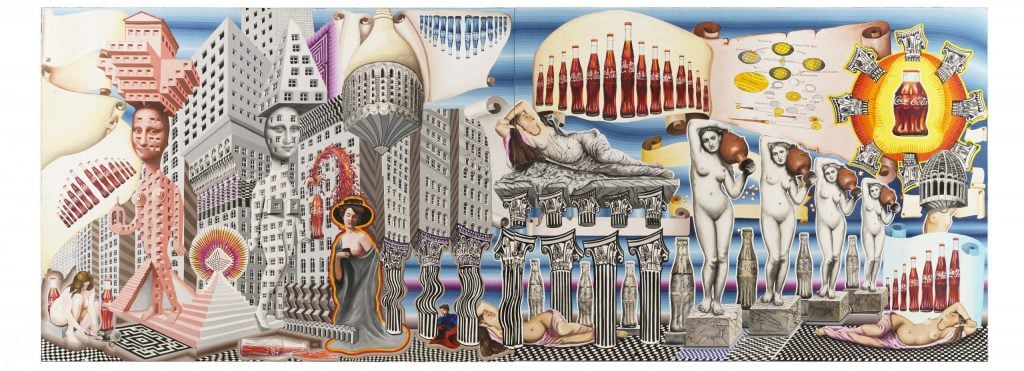

Pedro Friedeberg, Coca-Cola (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

But that’s not all. “Oh, and I miss there were people selling very small turkeys,” he added. There were flocks of turkeys walking down the street, like a man with a whip and 25 little turkeys walking down the street. It was more picturesque then, I suppose.”

He continued, “And the cars were really old and rickety going 20 miles an hour at the most. Some cars had rumble seats that you open the trunk, and you could seat two people, but they couldn’t communicate with the person who was driving, you had to knock on the window and say, stop or take me to this place. It was like living in another century.”

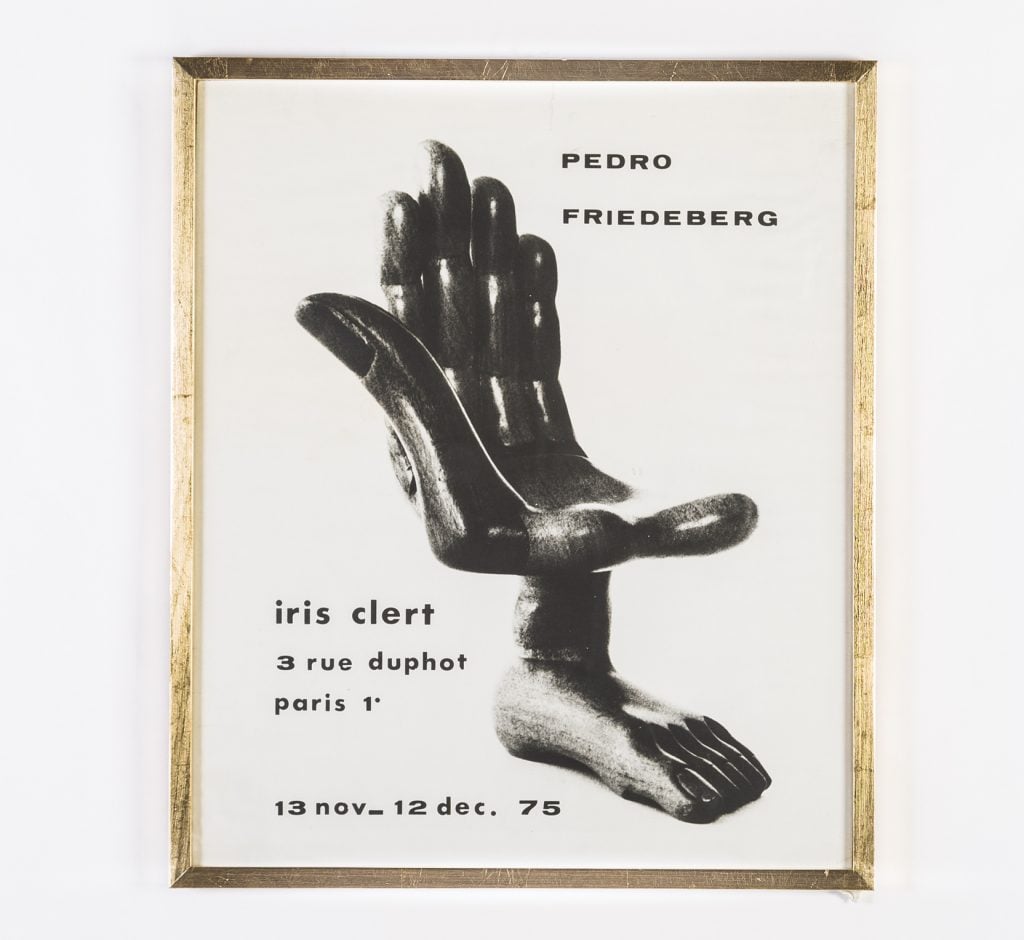

A 1975 poster for a Pedro Friedeberg exhibition in Paris. Courtesy of the artist.

Friedeberg’s op-art landscapes aren’t what come to mind when one thinks of traditional Surrealist tropes. “It’s just buildings on deserted streets,” he mused. “Italy was more like Mexico 70 years ago. There were also very few cars and, in the summer, this terrible heat and these streets with shade on only one side. Very mysterious. It was called metaphysical art. There’s a lot of good examples in the Museum of Modern Art here.”

Friedberg lived in New York in 1950 when he was 14. “I think my parents always wanted to get rid of me,” he said. “They sent me up by Greyhound Bus. It took four days and four nights from Mexico City to New York. I was fascinated. I’d never seen a skyscraper until I came to San Antonio, Texas.” After a stint in Boston, he returned to Mexico to attend architecture school in 1957. His studies play out in his complex renderings of made-up universes.

Pedro Friedeberg, Utopia y Ombligo (1965). Courtesy of the artist.

Friedeberg credits the mélange of his heritage with his upbringing, this confluence of cultures and experiences with affecting his artistic vision. “I feel my art is quite European,” he said. “It’s like French Surrealism. It’s not like German expressionism, or cubism maybe.” Is he depicting utopias in his intricate depictions of his mind’s eye? The artist shrugged and said, “I’m more making fun of things.”