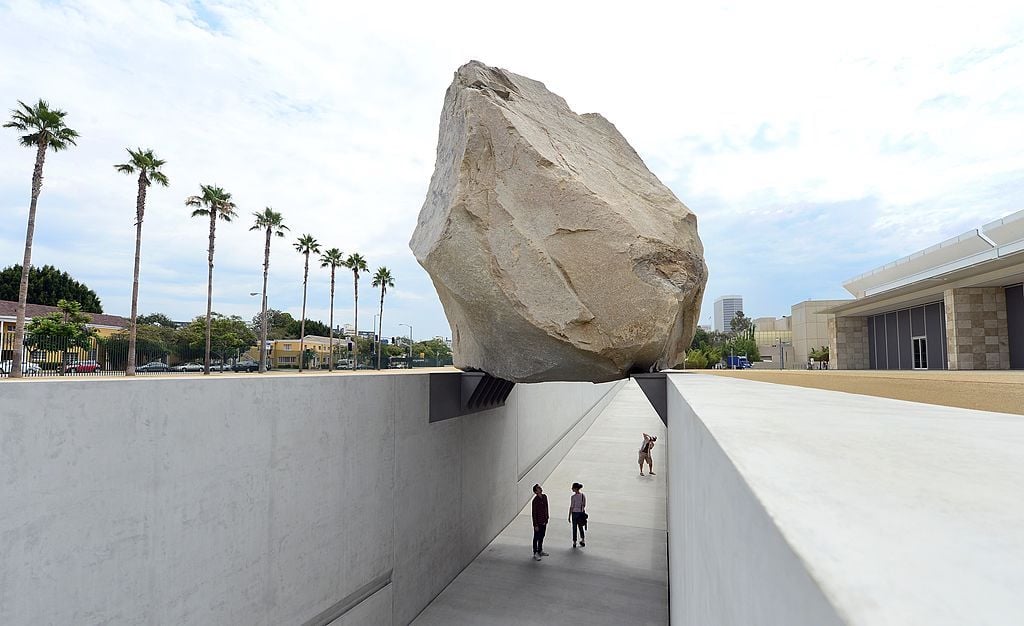

In his decade long tenure as director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Michael Govan has transformed and revitalized the institution to respond to the present-day community and visitors that it serves within Los Angeles county. A renewed focus on public projects and contemporary art installations saw the arrival of Chris Burden‘s Urban Light (2008)—which has become an LA landmark—and Michael Heizer‘s Levitated Mass (2012) refreshed the museum’s public image and caused attendance to almost double.

And he isn’t stopping there. A new half-a-billion dollar 400,000 square-foot building designed by architect Peter Zumthor is in the works to add some star power to the city. Construction is set to start in 2018 and is scheduled to be complete by 2022 or 2023.

On a tour of LACMA, we asked Govan about the role of museums in contemporary society, and what the future looks like for public museums amid an unprecedented rise in privately-owned museums.

Why do you think people like to attend museums and see art in the museum context?

Why is our attendance growing? Well, there are a lot of people here; we’ll hit 1.4 million people—which is not as big as the Met or places like that, but it’s pretty big, and it’s more than double what we used to have here. I think people with curiosity seek an education in what it is to be human and creative. And that curiosity is satisfied in a place that now can also be quite casual, pleasant and surprising to be in. So there is an aspect of education, and of entertainment and of a social milieu as well; coming with friends and meeting friends.

Chris Burden, Urban Light, 2008. Courtesy the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

How is the role of museums changing?

I think museum, big museums, are becoming public center pieces for cities, for metropolises. Because we sense our role is to create a place where culture and creativity and many cultures are on offer all the time. And so I think we take that civic role as seriously as we take the historic and preservation role of culture.

What is your view on the rise of private museums? And how it relates to competition for you?

One. There’s no competition at all from private museums in my mind for institutions like ours. There’s no private museum that even dares to do what we try to do in terms of the breadth of offering, the scale of public programs. I really don’t know one. You see private museums more as niche collections, and it’s fine to have them. You say rise but there was also in the ’30s and ’40s was a big rise in this country. At the end of the 19th century there was a rise in private museums too. The Guggenheim was a private museum; the Whitney was a private museum. A few of those private museums will become public; they’ll become big enough, their leadership will become responsive to the diverse concerns of their community rather than a specific collection or collectors and will morph into public museums. And then others won’t. Really, this is a case of more is more. Our culture benefits from more people who are willing to put their resources and energy, like Eli Broad, behind what they have accomplished and make it available to the public.

What do you make of the trend towards supersize museums?

I don’t actually think they’re that big yet! I’ve never heard that term “supersize.” I’m not sure we’re going to be building too many supersize museums. For example, when we’re finished with all this building—probably a billion dollar’s of investment over 20 years—we would fit into one part of one wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. So I think there is a limit on what might make sense for us here in Los Angeles, and I think we might be seeing that. Our strategy is probably less to continue adding here, than to maybe see off-site and satellites in other communities that could benefit.

Michael Heizer Levitated Mass (2012). Courtesy of Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images.

What sets LACMA apart from other museums in the US and abroad?

There’s maybe 10 museums in the US on our scale. So that sets us apart from all the other museums because it’s our mission—unlike even the Getty that has European painting, photography, and classical and ancient sculpture—is that we try to be everything. We really try to be entirely open with no limits, and so that does distinguish us from the more specialized museums. And what sets us apart in the US is that we’re among a category of museums that in the old days it used to be called an encyclopedic museum, so you’d have A-to-Z and try to say you hold the world. Of course, that definition is always changing, and I rather think of these kind of museums as almost “anything goes,” whether it’s design, graphic arts, film, or painting. We have this openness to many, many definitions of art.

What does the future look like for museums?

No-one knows the future, but I think the future is bright. I think museums keep enlarging their sense of mission in the community, the diversity of what they offer—and I mean literally the diversity—the diversity of their staffs, and their boards to try to respond to this diverse world we live in. As long as we keep doing that, I think that we will continue to be central to civic life.