Art & Exhibitions

Michelangelo’s Masterpieces Are Getting a High-Tech Makeover in a New Show

An experimental exhibition in Denmark is intended to spark debate about the future use of 3D-printed replicas in museums.

An experimental exhibition in Denmark is intended to spark debate about the future use of 3D-printed replicas in museums.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

When it comes to critically-acclaimed museum shows, a high premium is usually placed on the uniqueness and rarity of the objects on display. Back in the day, however, copies of an ancient masterpiece would often have to do. This was how the marvels of Greek art made their way to workshops across the Roman empire, in due course influencing the Renaissance masters and Western culture at large. Not only would ideas spread far via reproduction, but otherwise site-specific art could be appreciated in new contexts.

Carrying this spirit into the 21st century, the National Gallery of Denmark (SMK) will present the most comprehensive Michelangelo exhibition since 1875, featuring a groundbreaking blend of 19th-century plaster casts and state-of-the-art 3D-printed replicas. Opening March 29, the show will reassemble scattered masterpieces and showcase works that rarely, if ever, leave their original locations, offering visitors a unique opportunity to experience the Renaissance master’s art.

Plaster cast after Michelangelo Buonarroti, Medici Madonna. Original made ca. 1526–1532, cast in 1897. Photo: SMK – National Gallery of Denmark.

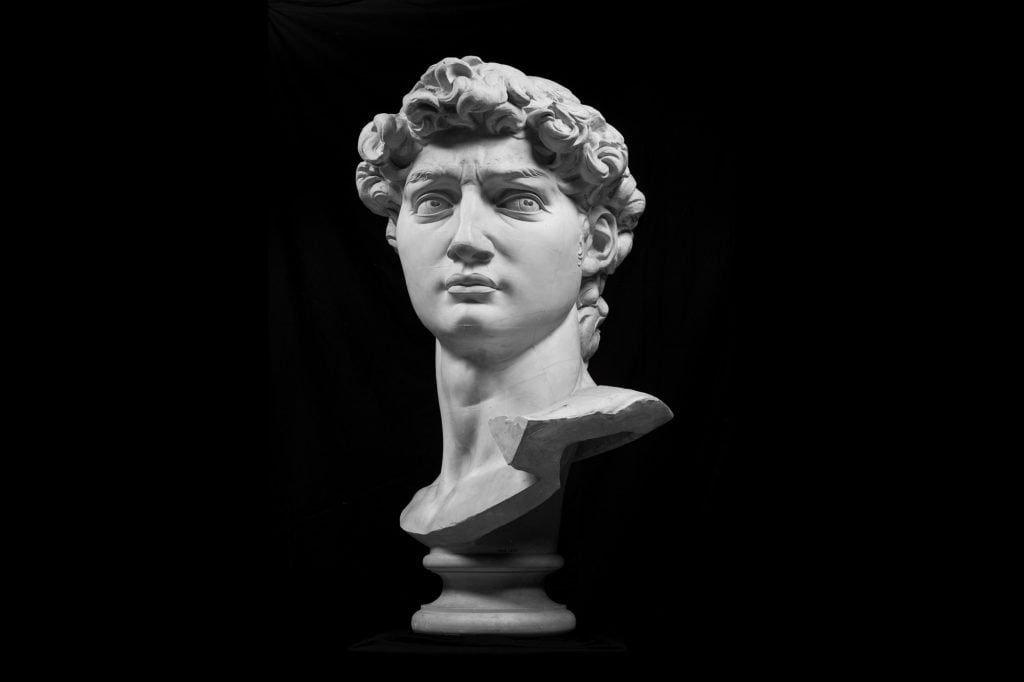

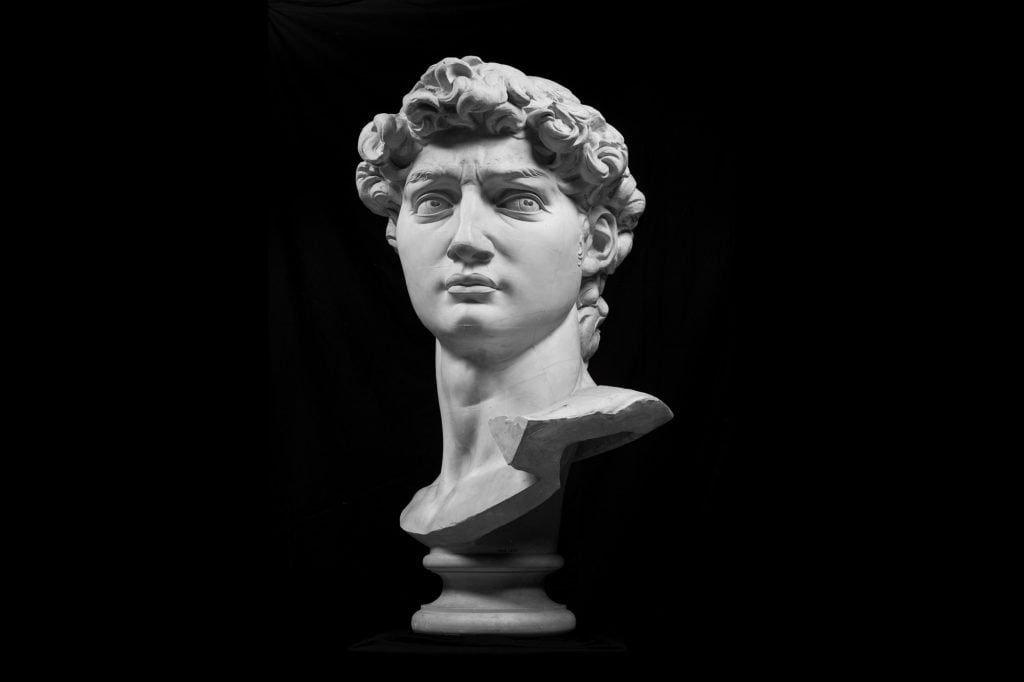

Using technology from Factum Arte in Madrid, the museum will enhance its collection of 19th-century plaster casts of Michelangelo masterpieces, such as the head of David and the Medici Madonna, with newly created 3D-printed replicas. These replicas provide access to works that are otherwise unattainable due to immobility or location. For instance, Michelangelo’s depictions of Saints Peter, Augustine, Paul, and Gregory are fixed elements of the Piccolomini Altarpiece in Siena, Italy installed so high that they cannot be easily viewed up close. Other works, like Cupid, are in high demand and geographically restricted, currently on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from France until 2029.

The show’s curator, Matthias Wivel, said he is not concerned that the use of replicas might be off-putting to audiences. “We will achieve a beautiful exhibition with them that will be compelling to the public,” he said. “The appreciation and study of art has always relied heavily on reproductions. Without them both would be much more limited. Used responsibly, there is huge potential and value in using reproductions.”

He conceded that the show is an experiment, and he will measure its success on its ability to “stimulate debate and prompt refinement or rejection, and innovation.”

Perhaps the strongest argument for the use of reproductions is greater freedom to build art historical narratives unbounded by practical limitations. For example, the show in Denmark will bring together several pieces originally produced for the tomb of Julius II that have since scattered across different locations. These include the Boboli Prisoners at the Accademia and Genius of Victory at the Palazzo Vecchio, both in Florence, and Rachel and Leah at San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome.

Plaster cast after Michelangelo Buonarroti, Day. Original ca. 1524-26, cast 1897. The Royal Cast Collection, SMK – National Gallery of Denmark Photo: SMK

Factum Arte have also been able to reconstruct Infant John the Baptist from Ubedà, which was smashed during the Spanish Civil War. Though the statue has been restored, it still bears the scars of its destruction; the new 3D model was made by referencing archival photographs of the work from before the restoration. Wivel hopes it will “convey some of the wonder of the original.”

The exhibition will also reveal how much reproduction technologies have evolved over the centuries. According to Wivel, Factum Arte’s facsimiles made using digital techniques are accurate down to the micron level, resulting in pieces of “much higher fidelity than the plasters, in that they reproduce the color, surface, and detailing such as veining, of the marble.”

He also noted that digital facsimiles like those made by Factum Arte provide highly detailed records of artworks that may be valuable to researchers and restorers for centuries to come. Wivel noted that traveling as part of exhibition loans can cause significant physical strain on fragile objects as well. In other contexts, high-tech replicas have also played an important role in facilitating repatriation agreements, allowing museums to keep a copy of an object that they decide to return.

Together, these reproductions, both old and new, will enable the most comprehensive monographic exhibition dedicated to Michelangelo since 1875, when the 400th anniversary of his birth was celebrated in Florence. Running through August 31, the exhibition will also include a selection of Michelangelo’s original drawings, correspondence, models in wax and clay, and several bronzes made after models that are now lost.