The news that Helen Molesworth, one of the most prominent curators in the United States, had been fired from her job at Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) on Monday sent shockwaves through the art world. During her three and a half years as chief curator of the museum, Molesworth drew accolades for her daring reinstallation of its collection, her fruitful partnership with the Underground Museum, and her scholarly solo exhibitions of Kerry James Marshall and Anna Maria Maiolino.

But behind the scenes, according to several sources close to the museum who were interviewed by artnet News, Molesworth’s personal priorities, progressive politics, and constitutional aversion to flattering donors put her on a collision course with the museum’s director and board. Ultimately, they said, the competing agendas and approaches proved irreconcilable, and the situation became untenable. (artnet News spoke to nine people for this article, five of whom asked to remain anonymous because of their relationships to the museum.)

The conflict at MOCA reflects broader tensions in the museum world over what, exactly, the job of a modern-day chief curator entails. Are they expected to set the artistic agenda of a museum? To fund-raise? To charm collectors into donating works of art? Or some combination of all three? At a time of rapid social change, what should a contemporary art museum’s priorities be, and what role should it play in its community?

These questions weigh particularly heavily on a museum that has been rocked by crisis after crisis over the past decade, from unsustainable spending that led it to the brink of closure during the recession to concerns over the direction of programming under former director Jeffrey Deitch.

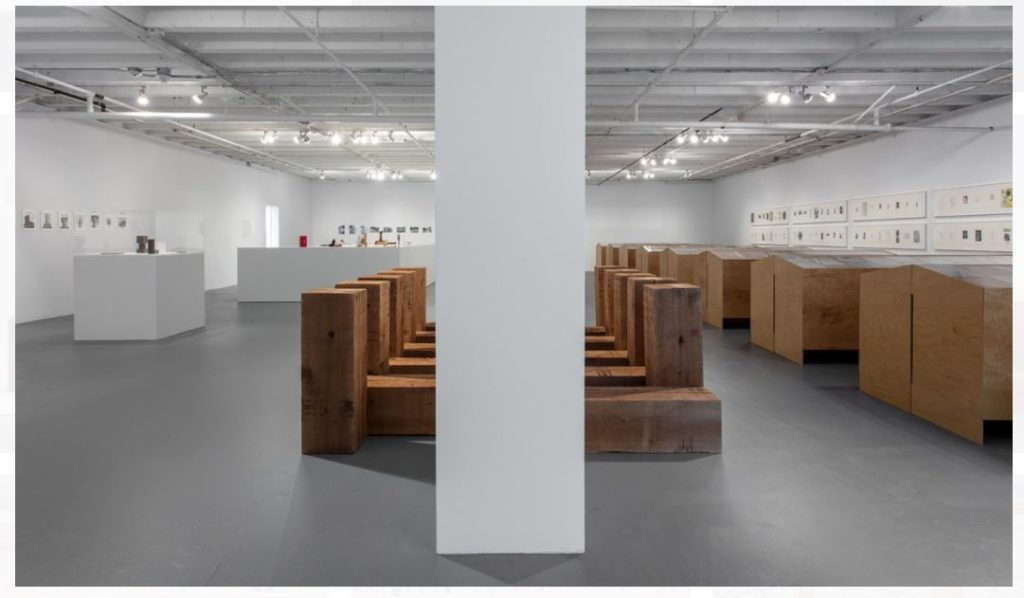

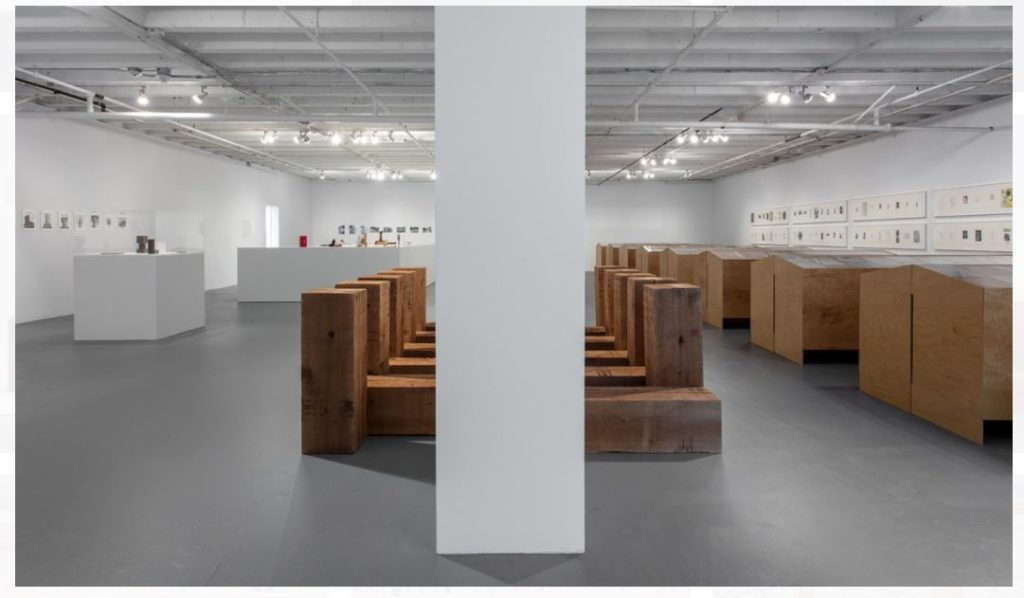

The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of MOCA.

Multiple sources say that Molesworth was not interested in the diplomacy and statecraft practiced by many chief curators, who approvingly tour private collections and lead donors around art fairs. If she was not excited by a particular collector’s holdings or an artist’s work, she did not hide that fact. And she told some that she was not particularly interested in art made by white men. Instead, she pursued projects by lesser-known women and artists of color—an agenda that some powerful donors and members of the board did not share. (Molesworth did not respond to requests to comment for this story.)

In a statement provided to the Los Angeles Times on Tuesday, the museum said that it had decided to “part ways” with Molesworth “due to creative differences.” The artist and museum trustee Catherine Opie, however, said that the museum’s director, Philippe Vergne, had told her a different story: that Molesworth had been fired for “undermining the museum.”

Discord Within

Although the exact reasons for Vergne’s termination of Molesworth remain opaque, sources say that distrust has been seeping into the groundwater of MOCA for some time—and that goodwill is in short supply.

Molesworth, among others at the museum, reportedly objected to Vergne’s decision to mount a solo exhibition of work by the Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre (who was tried and acquitted of the murder of his wife, artist Ana Mendieta, in 1985), arguing that it was not the right moment for such a show. The exhibition, curated by Vergne, closed in July of last year.

Installation view of “Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010” at MOCA. Photo: Brain Forrest, courtesy of MOCA.

Tension also arose, multiple sources said, when Molesworth sent a junior curator in her place to meet with the artist and MOCA board member Mark Grotjahn about his upcoming solo exhibition at the museum. The move was seen by some as a deliberate snub. (Grotjahn did not respond to a request for comment.)

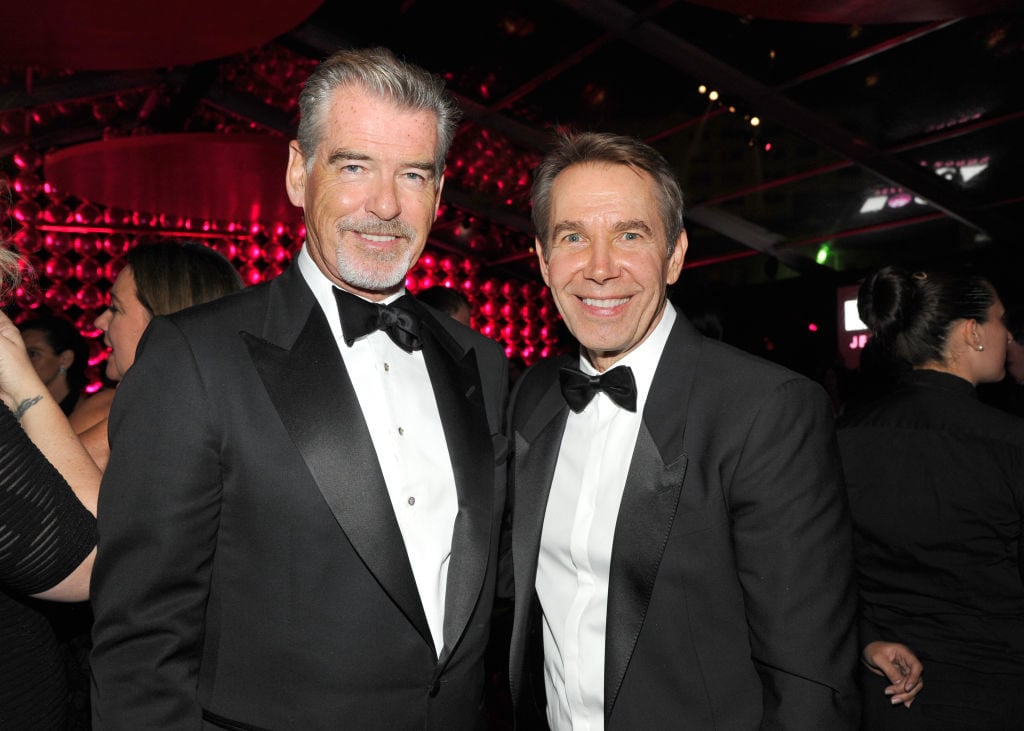

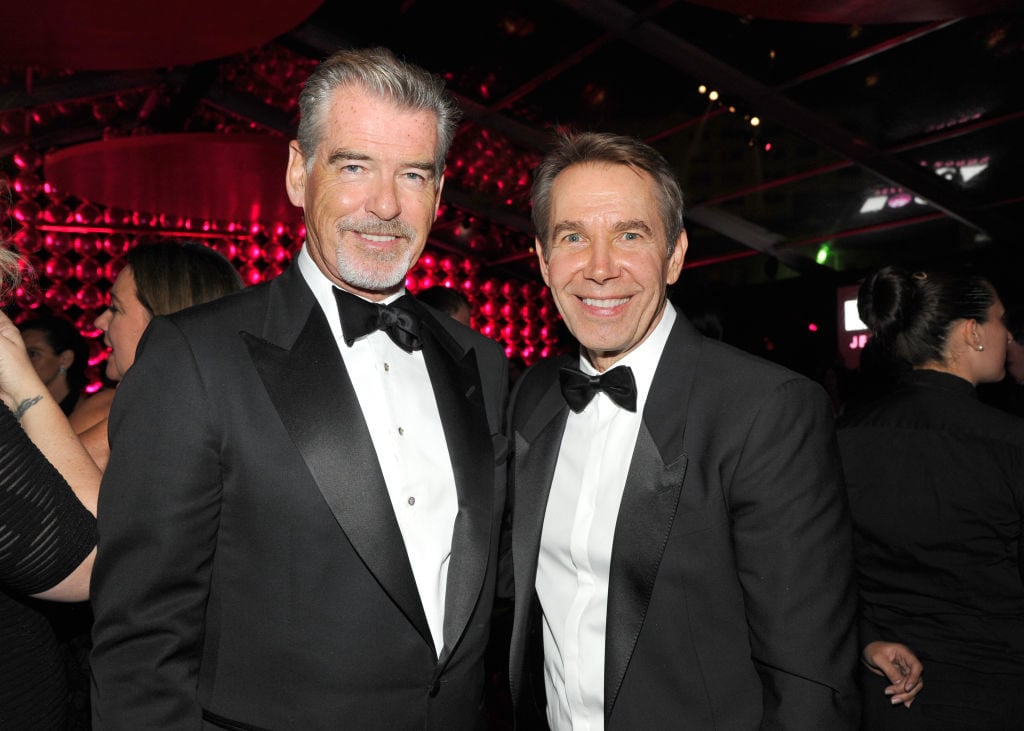

Notably, a number of wealthy MOCA board members are known to be collectors of Grotjahn’s work; the board had also planned to honor him at its annual fundraising gala this year. After save-the-dates had already been sent out, however, Grotjahn declined the honor, noting that all the previous honorees were, like him, white men. (In 2017, artnet News learned, the museum had originally intended to honor Catherine Opie, but the board opted for Jeff Koons instead.) On Friday, the museum decided to cancel this year’s gala altogether. The Los Angeles Times reported that the $1.4 million in pledges would be returned to donors.

One source close to the museum told artnet News that the artist Lari Pittman, who resigned from the board in January, “said it best” when he told the Times last month: “It’s a vision problem in what the board wants, what the director wants, and what the curatorial team wants. Their visions are very different. I’m leaving because I don’t see any current resolution given all the players.”

Actor Pierce Brosnan (L) and honoree Jeff Koons at the MOCA Gala 2017. Photo by John Sciulli/Getty Images for MOCA.

Happy Artists, Unhappy Donors

Artists have praised Molesworth for providing a platform for important figures who have previously not received their proper due. The artist Andrea Fraser, the chair of UCLA’s art department, told artnet News that the curator “was fostering what was becoming one of the most diverse and innovative programs in any major museum in the US.”

But in the clubby Los Angeles art-collecting community, Molesworth’s particular focus also sometimes rubbed donors—and perhaps more importantly, potential donors—the wrong way. One collector said he ultimately decided to donate a significant work to another museum instead of MOCA after Molesworth came to see his collection and made her lack of interest apparent.

“It made me feel naked—it made me feel uncomfortable because she came to see my collection and made me feel like she really didn’t like it,” the collector told artnet News. “She didn’t even pretend to like it.” The exchange was particularly stark compared to friendlier encounters he had had with chief curators from other museums, he said.

Meanwhile, some have raised concerns about Molesworth’s management. Former employees of MOCA told Frieze and Hyperallergic on Thursday that Molesworth failed to mobilize the staff, and that long-serving curators, registrars, and preparators left or were fired during her tenure. One staffer told Frieze that they left the museum because Molesworth “made their daily work lives miserable.”

David Bradshaw, the former technical manager for exhibitions at MOCA, worked at the museum for 28 years until, he told Hyperallergic, Molesworth fired him a year and a half ago. He said he was “the last of a particular group of people that she targeted for removal from the moment she arrived—longtime staff whose personalities rubbed her the wrong way.”

Current MOCA employees directed inquiries from artnet News to the museum’s press office, which declined to comment on personnel matters.

Philippe Vergne, Kerry James Marshall, and Helen Molesworth at the opening of Kerry James Marshall: Mastry at MOCA. Courtesy of MOCA via Instagram.

A New Beginning?

When Vergne and Molesworth joined MOCA in 2014, their arrival was heralded as a new beginning for the institution, which had endured budgetary woes and media scandals under the previous leadership.

Indeed, the past decade has been a tumultuous one for MOCA. In 2008, few knew whether the museum would survive. Amid the financial crisis, it drew from its endowment to remain solvent, leaving the fund with a paltry $5 million.

Today, according to a spokeswoman, that endowment stands at $138 million. She added that the museum has had a balanced budget for the past four years and expects to have one this year as well. Attendance, she noted, has gone up from roughly 275,000 visitors in 2016 to around 333,800 in 2017.

Tax filings, however, suggest that the donations that surged immediately after Vergne’s arrival have declined. During the fiscal year of 2014, after Vergne joined the museum and launched a $100 million fundraising campaign, MOCA reported $88.5 million in contributions and grants, according to its tax filings.

But as time went on, those numbers eroded. During the fiscal year of 2015, the museum reported $38.4 million in contributions and grants. The following year, the most recent for which information is publicly available, that figure dropped to $18.6 million. This level is on par, however, with several other organizations of similar size, each of which reported between $10 million and $30 million in contributions that year, according to tax filings examined by artnet News. But the picture suggests that the pressures of fundraising and securing patrons were not distant from the museum’s mind.

Artists’ Reactions

So far, artists have reacted to Molesworth’s dismissal with surprise and dismay. Many feel protective of the museum, which was founded by artists in 1979, and pained by its turbulent recent history.

Fraser said she considered Molesworth’s firing “a huge mistake,” calling it “yet another terribly unfortunate personnel change in what has now become a long line of unfortunate hirings, firings, and resignations” at the museum.

“MOCA as an institution does seem to be on a trajectory where it can’t figure out what it wants to be,” the artist Nayland Blake, who has work in MOCA’s collection, told artnet News. “Museums need to decide whether or not they are active participants in the life of their city or if they are just some kind of trophy house.”

Installation view of “The Art of Our Time” at MOCA Grand Ave, courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo by Brian Forrest.

Blake noted that the museum’s board and director should have been aware of Molesworth’s interests before she was hired. “Helen’s reputation precedes her—this is the type of work that she’s interested in, the type of work she’s championed,” he said. “Why would you hire her to come in and do something else?”

He also wondered whether Molesworth’s approach would have been received differently if she were a man. Many have drawn a comparison between Molesworth’s situation and those of two other female museum directors, Laura Raicovich and María Inés Rodríguez, who recently resigned under pressure or were fired from their positions after conflicts with leadership. “It happens across the corporate world: you hire men for their opinions and women for their compliance,” he said.

Indeed, for many artists, the departure of Molesworth has tapped into deep-seated concerns about the direction of museums across the country.

The artist Dara Birnbaum told artnet News in an email: “As an artist in MOCA’s permanent collection, now living in a social construct, which challenges us every day, it is important to know that a progressive woman can have a secure voice within an important art institution. Many museums take the less high road: spinning off all too well-known names of especially male artists, whom one might even consider corporate in statement, appearance, and even their zeal. Molesworth made some ‘tougher’ choices; the road less traveled. It is not only a disappointment to see a valuable attribute, such as chief curator Helen Molesworth, ‘fired’—it is also an action that undermines our very ability to progress precisely when this is more than ever necessary.”

Artists are not the only ones feeling despair about the role of museums today. In a passage from Molesworth’s essay in the latest issue of Artforum on the work of Simone Leigh, which began to be widely circulated after news of her termination broke, the curator herself concluded: “The museum, the Western institution I have dedicated my life to, with its familiar humanist offerings of knowledge and patrimony in the name of empathy and education, is one of the greatest holdouts of the colonialist enterprise. Its fantasies of possession and edification grow more and more wearisome as the years go by.… I confess that more days than not I find myself wondering whether the whole damn project of collecting, displaying, and interpreting culture might just be unredeemable.”