Art World

Protest or Patriotism? Why One Artist Wants You to Join Her in Writing Out the Constitution by Hand

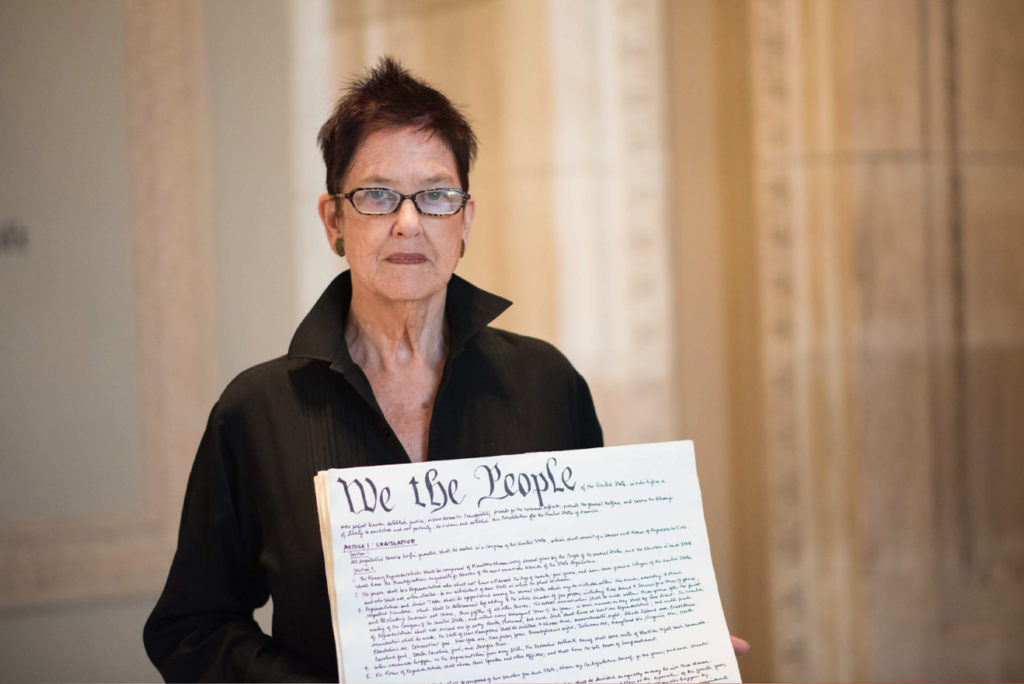

Morgan O'Hara wants Americans to consider the words of the Constitution.

Morgan O'Hara wants Americans to consider the words of the Constitution.

Sarah Cascone

Like many artists, Morgan O’Hara felt compelled to create work in response to the election of Donald Trump. On the eve of January’s inauguration, she set off to hand copy the US Constitution in her own personal form of artistic protest.

As a child, O’Hara learned to improve her penmanship by being instructed to copy poetry and important texts. “It’s a practice from my European education that I’ve never really left behind,” she told artnet News, noting that she regularly enjoys copying passages that she particularly enjoys—although she hadn’t done so with the Constitution before. “My main practice is drawing, and writing and drawing are not so far from each other.”

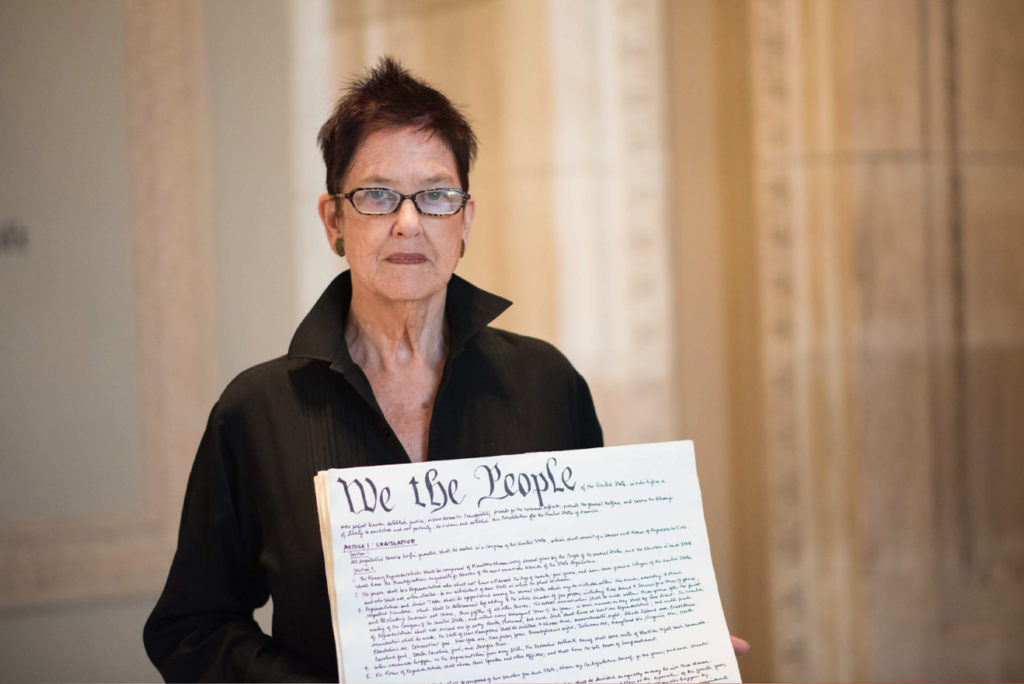

O’Hara chose the Rose Reading Room at the main branch of the New York Public Library, a spot she’s always loved, to host the project. (She didn’t seek official permission from the library, although her work was the subject of a 2012 exhibition there, featuring her “Live Transmission” drawings depicting the motion of her subjects, some of whom were patrons of the Rose Reading Room.)

Library patrons participating in Morgan O’Hara’s “Handwriting the Constitution” project. Courtesy of Alessandro Cassin.

As Trump was delivering his inaugural address on January 20, O’Hara was seated under the warmly colored cloud murals on the library’s soaring ceiling, armed with markers, pens, and pencils, and a stack of spare notebooks and blank papers. She was hoping others would see what she was doing and be moved to participate, giving them a chance to reflect on the words of the Constitution.

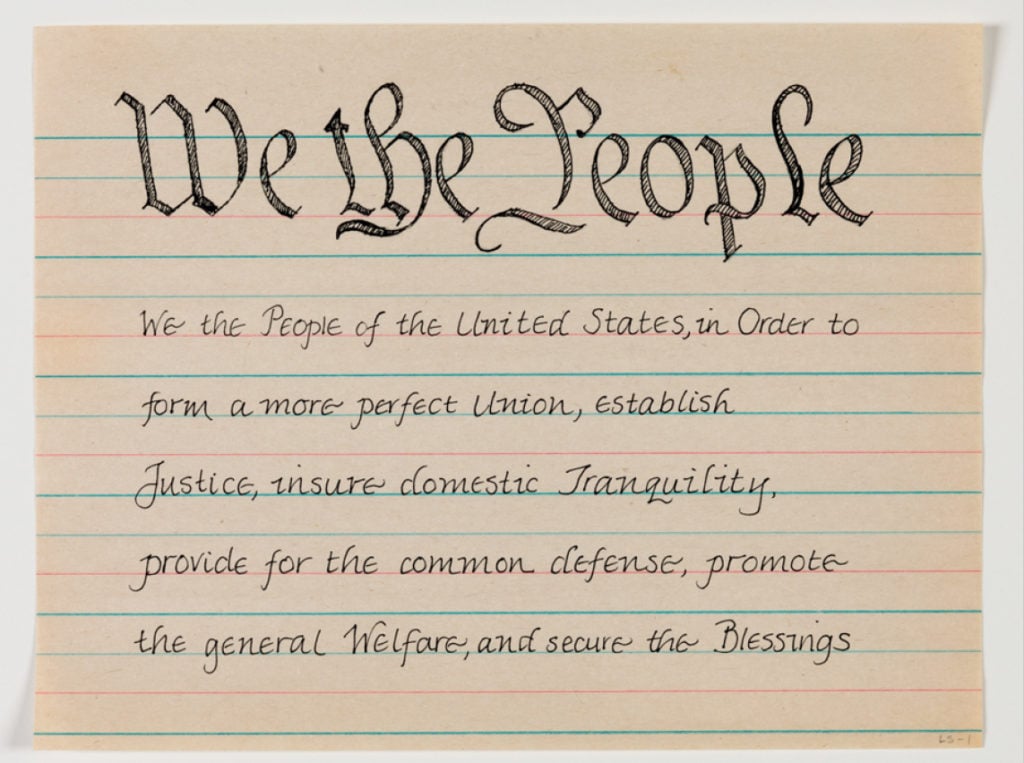

“Hand copying a document can produce an intimate connection to the text and its meaning. The handwriter may discover things about this document that they never knew, a passage that challenges or moves them,” wrote O’Hara in the New York Times. “They may even leave with a deeper connection to the founders and the country, or even a sense of encouragement.”

As the day went on, sure enough, O’Hara was joined by friends, and then by other library patrons who became interested in what she was doing. “It’s interesting how much variety there is in people’s handwriting,” she told artnet News.

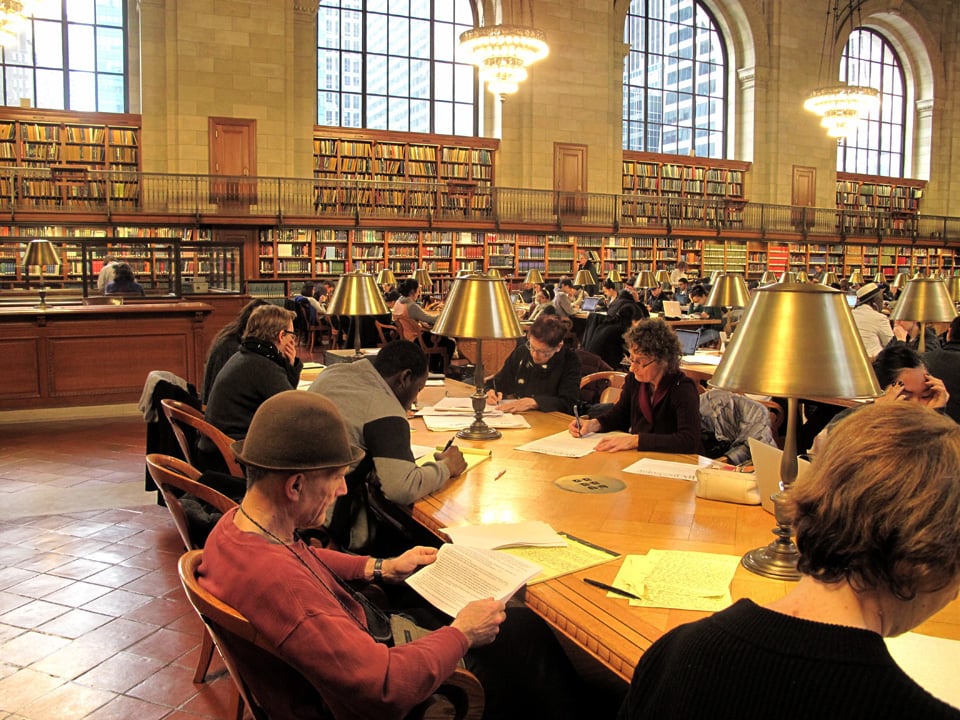

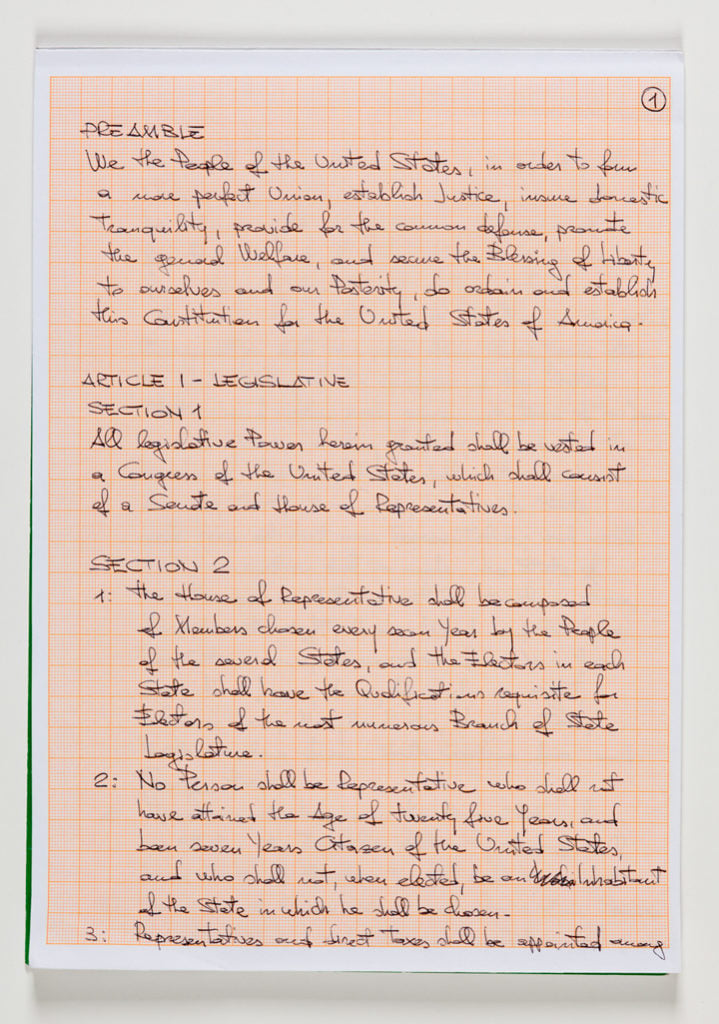

Linda Stillman, a handwritten copy of the Constitution, part of Morgan O’Hara’s “Handwriting the Constitution” project. Courtesy of Jeanette May Morgan.

O’Hara has continued the project, titled “Handwriting the Constitution,” on a monthly basis ever since, offering the public a way to remind themselves of the bedrock of our democracy at a time where political unrest is running high.

Despite the document’s essential importance, recent events suggest Americans aren’t as familiar with our country’s foundational political texts as they perhaps ought to be. This month, when NPR tweeted the Declaration of Independence on Independence Day, a number of Trump supporters didn’t recognize it, and some accused the radio station of condoning violence.

Mireya Grasso, a handwritten copy of the Constitution, part of Morgan O’Hara’s “Handwriting the Constitution” project. Courtesy of Jeanette May Morgan.

O’Hara wasn’t surprised. “After the electoral process we just went through, nothing surprises me anymore,” she said. “The Constitution is a revolutionary text, and the Declaration of Independence is even more revolutionary—it caused a war!” (The Declaration of Independence was written in 1776, one year into the Revolutionary War, and the Constitution was completed in 1787 and ratified over the next three years.)

Tapping into that sense of history is important for O’Hara, who completed her third copy of the Constitution on handmade Italian paper dating to the 1700s, given to her as a gift while she was living there. “It was used for a tailor’s accounting book, with entries from 1792–1794,” she said. “The Constitution was written just a few years earlier, so it made perfect sense to put the two documents together.”

Morgan O’Hara, a handwritten copy of the Constitution written on 18th-century handmade Italian paper, part of her “Handwriting the Constitution Project.” Courtesy of Morgan O’Hara.

In a politically divided country, “Handwriting the Constitution” is proving to be something of a uniting force. One Trump voter from Seattle told O’Hara he thought her Times article was born out of a particularly left-leaning issue but still wanted to participate in the project. People in Alaska, Texas, California, New Hampshire, Utah, Michigan, Washington, and Illinois have all reached out about starting Constitution writing groups of their own.

“My goal with it is to get away from all this negative, toxic stuff and do something that’s positive, educational, grounding, and potentially encouraging,” O’Hara explained.

Leo Ghirardi, a handwritten copy of the Constitution, part of Morgan O’Hara’s “Handwriting the Constitution” project. Courtesy of Jeanette May Morgan.

To that end, the Constitution is just the beginning. “I’m interested in bringing to light all the documents around the world created in protection of human rights,” O’Hara said. “I’ve been invited to hand write the Magna Carta in Dublin next year. It was written in the year 1215.”

For those in New York, the next session at the New York Public Library on Saturday, July 29 1 p.m.–5 p.m. You can also email the artist about getting involved.

“The work is really important,” said O’Hara, who is looking to expand the movement nationwide. “Of course we know the Constitution is there, but handwriting it, one realizes that these are our rights and people can’t take them away.”