Inside Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, glimmers of a once vibrant and beautiful metropolis strive to shine through its bomb-blasted structures. In October 2016, two years after the Islamic State (ISIS) took over the city, a U.S.-led military offensive was waged to take it back from the terrorist group. The city and its people experienced one of the deadliest urban battles since World War II, and nothing was left unscathed during the nearly year-long military assault.

Much of the Old City of Mosul was destroyed. The aftermath is a haunting sight: once grand historic buildings still lie collapsed into rubble, the facades of most structures are riddled with bullet-holes, and empty, bomb-shelled buildings line every street. While Mosul and its people will never be the same, reconstruction efforts are underway by international groups.

One such building given new life is the Mosul Cultural Museum. The second largest encyclopeadic institution in Iraq after the National Museum in Baghdad, the Mosul Cultural Museum was inaugurated by King Faisal II in 1952 to tell the story of northern Iraq. The collection inside was of global importance, encompassing artifacts from prehistory, Assyria, Hatra and Islam.

But when ISIS took over Mosul in 2014, the museum was targeted and its objects were destroyed or looted. Major Assyrian monuments that were damaged by the extremist group include a colossal lion from Nimrud, two lamassu guardian figures, the significant Banquet Stele, and the throne base of King Ashurnasirpal II. Over 28,000 books and rare manuscripts were burned.

The damaged entrance of the Mosul Cultural Museum in 2021. Photo: courtesy of the Mosul Cultural Museum.

In a video released by ISIS in 2015, the group destroyed antiquities in the museum while an ISIS preacher stated: “We’re ridding the world of polytheism, and spreading monotheism across the planet.” The militants destroyed statuary from the second-century city of Hatra with sledgehammers.

In the Assyrian Gallery, the part of the museum that suffered the most damage during ISIS’s attack, the group placed dynamite under a ninth-century B.C.E. platform for a carved stone with intricate cuneiform writing. It was blown to pieces.

“In the destruction of this museum, ISIS was trying to destroy the memory of the Iraqi people,” Zaid Ghazi Saadallah, the director of the Mosul Cultural Museum, told Artnet News.

Now, signs of reconstruction can be found inside and surrounding the museum, as it gears up to fully reopen to the people of Mosul in 2026. As Saadallah walked around the museum, he motioned to parts of it that had been fully rebuilt, other parts in the process of being restored and others still that will be left with the scars of war.

In the Assyrian Hall, a large, gaping crater where ISIS detonated the bomb remains in the floor. Its jagged edges seem almost fresh—and that’s the way the people of Mosul want it to stay. When the museum reopens, the memory of the devastating attack will be preserved. Visitors will be able to view it from the mezzanine above, now a metaphorical wound-turned-shrine filled with light. “ISIS also wanted to destroy the memory of the world—these artifacts are part of world history,” Saadallah said.

Mosul Cultural Museum staff document the damage in the Assyrian Hall in 2019. Photo: courtesy of the Mosul Cultural Museum

“Iraqi heritage is important to the world,” Laith Hussein, head of Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), told Artnet News. His agency, part of the country’s Ministry of Culture, is overseeing the restoration project alongside the Musée du Louvre, the Smithsonian Institution and the World Monuments Fund, with funding and support from the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas (ALIPH).

“Many important pieces in the Mosul Cultural Museum were damaged and stolen by ISIS. Now, many international organizations are helping us to find and return the artifacts.” Hussein said the objects will eventually be displayed back “where they belong.”

In May, in the newly restored Royal Hall next door, the museum opened a month-long exhibition, “The Mosul Cultural Museum: From Destruction to Rehabilitation,” the first showcase of artifacts from its collection since the war.

When the museum fully reopens, many of the objects on display will be those saved from destruction when they were moved to the National Museum in Baghdad before the start of the Iraq War in 2003. These items remain in storage for the time being, to safeguard them from further plunder. Additionally, gallery spaces will exhibit artifacts from ongoing archeological excavations in Nineveh and pieces that have been restored by the Louvre’s conservation team.

Artifacts are documented and inventoried by museum staff in 2022. Photo: courtesy of the Mosul Cultural Museum.

“The city of Mosul is crucial to an understanding of world history,” added Tanvir Hassan, director and deputy chairman at the architectural firm Donald Insall Associates, which is leading the museum building’s restoration. “This is the Assyrian capital of the world. Our whole genesis and understanding of history begins here along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, the Fertile Crescent. This is the basket of civilization as we know it.”

Mosul’s rich heritage led to the creation of other local museums, such as the one at the archaeological site of Nineveh, built in 1956 during the restoration of the Nergal Gate.

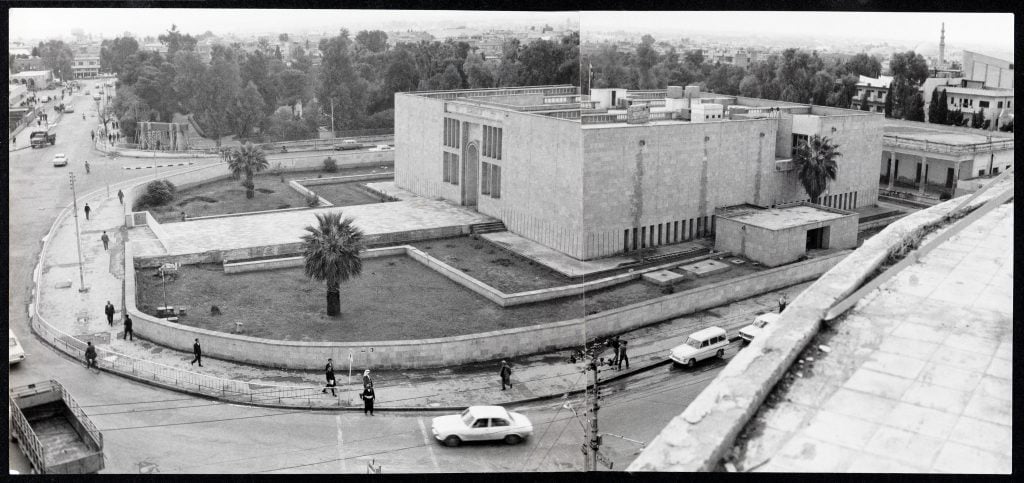

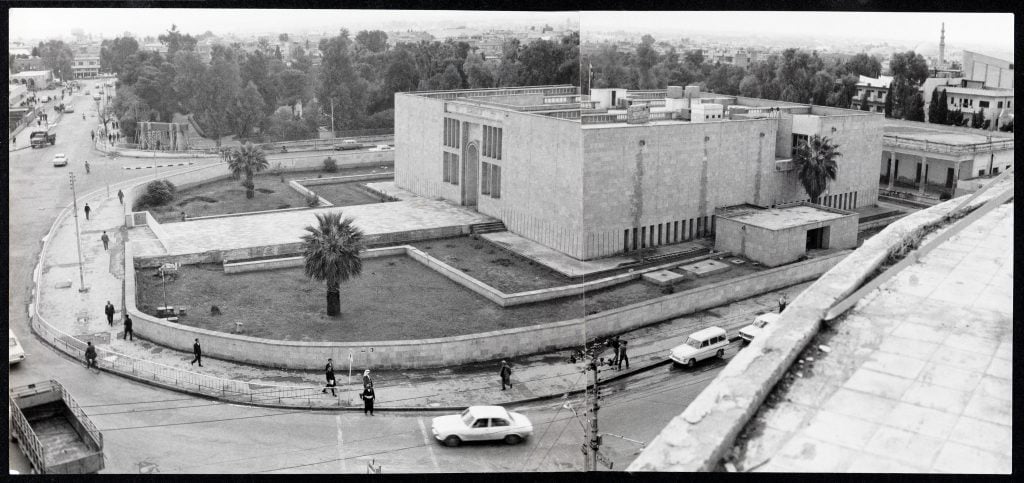

But the Mosul Cultural Museum, which first opened to the public in 1974, was different. It was designed by Iraq’s leading Modernist architect of the time, Mohamed Makiya, at the height of his career. “He was an important figure in forging a modern identity for Iraq,” Hassan said. “Through his architectural design, Makiya incorporated Assyrian aesthetics onto a white Modern box structure.” The new museum is being reconstructed according to Makiya’s original plan.

The construction of Mosul Cultural Museum is completed (1972). Photo: courtesy of the Mosul Cultural Museum

Challenges to Mosul’s reconstruction remain. While the few remaining ISIS cells are now largely found in rural areas, there have been a few kidnapping attempts near Mosul in recent years. And despite a period of relative stability on the ground, Iraq’s politics remain chaotic and corrupt, and any flare-up in fighting could quickly test Mosul’s fragile rebuilding efforts.

There are also still active land mines around Mosul, and this poses the biggest challenge for the city’s residents and those involved in reconstruction. Many people have been injured in the process and a handful of children have died, according to local sources.

“The old city is highly contaminated, and Tetra Tech, the American company, is in the process of clearing part of the city,” said Qassim Abdulrahman Khudhur, an Iraqi translator. He added, however, that “this is a time-consuming task.” And rebuilding can only begin after sites are de-mined.

A view of an ordinary street in Mosul. Photo: Rebecca Anne Proctor.

“When a bomb goes off, the destruction takes seconds,” said Ariane Thomas, director of the Department of Ancient Middle Eastern Antiquities at the Louvre. Thomas is working with Mosul museum staff to conserve and reconstruct three major stone sculptures (the Banquet Stele, the throne base, and the lion of Nimrud) and fragments of metal plaques recovered from the site of Balawat, so that they can be displayed once again.

Once the restoration works are complete, the goal is for the museum to resume its position as a cultural landmark for the citizens of Mosul, and more widely, as a cultural center for the Middle East and the world.

“Reconstruction can take forever,” Thomas said. “The museum, like Mosul, will never be the same again.”

A visualization of the rebuilt mezzanine floor of the Mosul Cultural Museum with a view of the main entrance. Photo: courtesy of the Mosul Cultural Museum.

More Trending Stories:

A German Museum Came Up With an Insanely Low-Tech Solution to Protect Its Rembrandt Canvas From a Leaky Ceiling

A 17th-Century Double Portrait of Black and White Women, Said to Be of ‘Outstanding Significance’ Will Remain in the U.K.

Art Industry News: South Korean Student Thought a Museum Wanted Him to Eat the $120,000 Duct-Taped Banana + Other Stories

This Famed Dollhouse Is Hung With Tiny Original Artworks, Including a Miniature Duchamp. Here Are Three Things to Know About the One-of-a-Kind Treasure

The Brooklyn Museum’s Much-Criticized ‘It’s Pablo-matic’ Show Is Actually Weirdly at War With Itself Over Hannah Gadsby’s Art History

Elisabetta Sirani Painted in Public to Prove Her Work Was Her Own. Here’s How She Became a 17th-Century Star—and Why She’s Being Remembered Now

The Venice Biennale Has Announced the Highly Anticipated Curatorial Theme of Its 2024 Art Exhibition