At MSCHF’s upcoming exhibition at Perrotin—the art collective’s first show at a commercial art gallery—you can literally trade a gun for an artwork.

That transaction forms the basis of an ongoing project called Guns 2 Swords, for which MSCHF takes peoples’ guns, forges them into the shape of the ancient weapon, then returns the objects to their owners. Perrotin is on board: the gallery has agreed to accept firearms in exchange for a discount on this particular body of work. (Arrangements need to be made in advance; visitors are not allowed to bring guns into the gallery.)

Guns 2 Swords is just one of many offbeat projects that MSCHF, whose members are masters of wringing profundity from provocation, have cooked up for their exhibition, “No More Tears, I’m Lovin’ It.”

The group plans to convert the gallery into a kind of derelict strip mall, with each “store” dedicated to a discrete body of work. Alongside the sword shop, there is a “GameStop,” which will house crude video games the group has designed, and a “Footlocker,” offering paintings of feet and distorted reproductions of classic shoes. (The collective’s most infamous project, a series of modified Nike Air Max 97s sneakers with drops of human blood mainlined into their soles, will not be available.)

Rounding out the show, which opens November 3, is a life-sized marble sculpture of Jennifer Lopez, based entirely on paparazzi photos. It’s a clever concept that checks a lot of 2022 boxes, fusing ideas about celebrity, the threat of the surveillance state, and the power of A.I. into a piece of art that looks like it was carved by Michelangelo. Meanwhile, in a performance piece planned for the exhibition’s opening, the rapper 24KGoldn will sit behind a gallery wall with only his hand available to be seen or touched.

MSCHF’s Chair Simulator (2022) video game. Courtesy of MSCHF.

The show marks MSCHF’s entrée into the capital-A Art World, which may say more about the industry’s temperament than the group’s work. Though the collective (pronounced “mischief”) has taken contemporary art as a subject before—they once bought a $30,000 Damien Hirst spot print, cut it into 88 pieces, then sold them for $480 a pop—the world of galleries and museums has never reciprocated the interest. (A reimagined version of the Hirst work, called Severed Spots, will be on view at Perrotin.)

Beyond the white cube, however, MSCHF has become a cult-favorite brand since its founding in 2019.

Their “drops,” which are released exactly every two weeks, once felt like internet stunts conceived in a dorm room: a rubber chicken-shaped bong, an app that lets you watch Netflix at work. Some still hew toward childish gaggery—they recently released a series of ketchup packets that alternately contained either the condiment or makeup—though the more the group continues to churn out their idiosyncratic products, the more it feels like what they’re after is one big, and often very clever, art project.

It was Emmanuel Perrotin, the founder of the eponymous gallery, who approached MSCHF about working together. “I was immediately intrigued by their mission of critiquing institutional systems from within,” Perrotin told Artnet News. “It has been part of the gallery’s vision from the beginning to work with artists who break the boundaries of what is considered to be fine art.”

Indeed, perhaps more than any other major dealer, Perrotin has shown the ability to transform pop-inclined art-world outsiders into bona fide industry stars, JR and Takashi Murakami among them. The artist to whom MSCHF is most often compared, Maurizio Cattelan, is also a Perrotin artist; it was at the gallery’s Art Basel Miami Beach booth that he taped a banana to the wall, spawning countless headlines and outraged social media posts. One would imagine that the dealer sees potential for a similar response with MSCHF. (The collective is planning a special project for Perrotin’s ABMB booth this year, though details are still being worked out.)

“While these artists might seem like no-brainers now, each artist was a risk early on in their career,” Perrotin said. “I believed in each one’s vision, as I do with MSCHF.”

“We don’t think there’s anything illegal in the show,” noted Kevin Wiesner, one of MSCHF’s original members. “I think Emmanuel is slightly disappointed that that’s the case.”

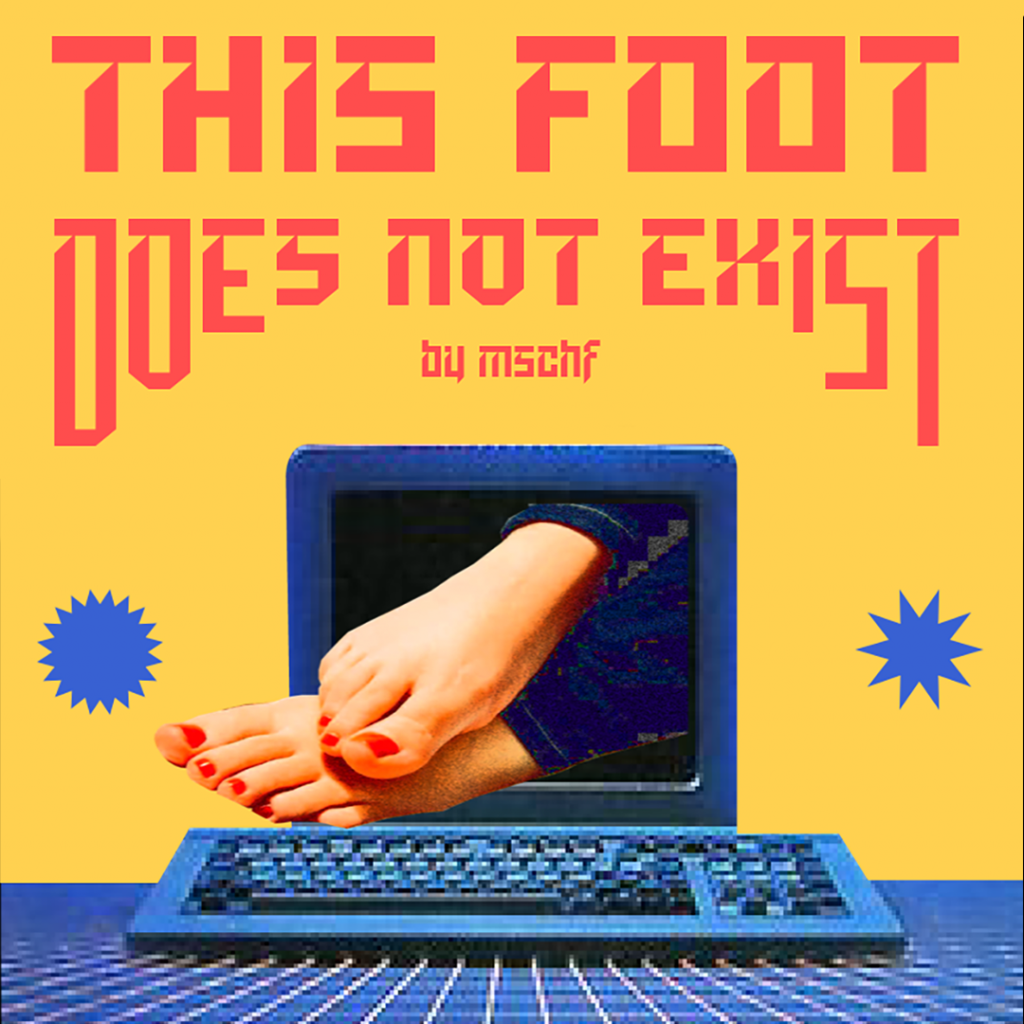

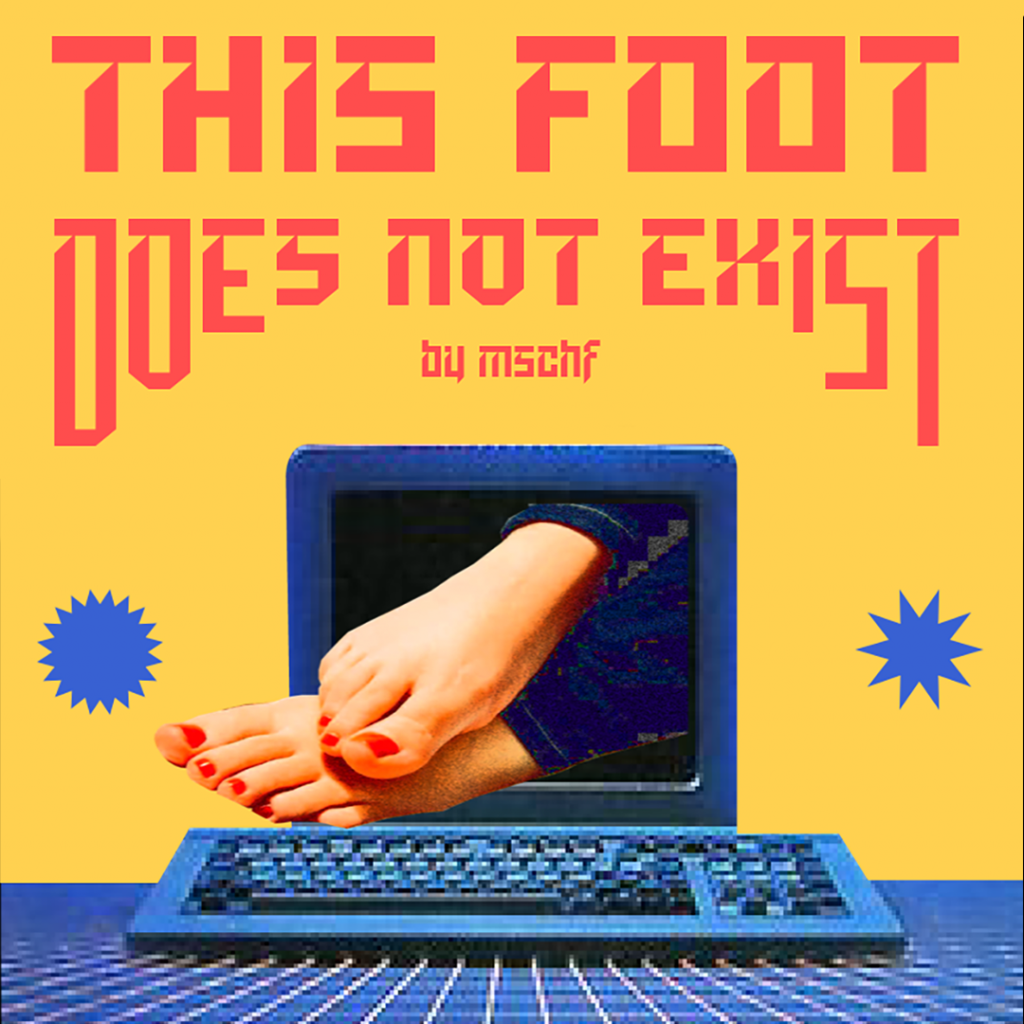

MSCHF, This Foot Does Not Exist (2020). Courtesy of MSCHF.

Most articles written about the collective, especially early on in its history, arrived with different versions of the same question in their title: What is MSCHF? Is it a business? A brand? An artwork? A hoax?

That remains a tricky question to answer. MSCHF is registered as a Delaware corporation under the name MSCHF Product Studio, Inc. It’s backed by venture capital firms and the group’s five founding members all have startup-friendly titles. Gabe Whaley is CEO, Dan Greenberg is CRO, Stephen Tetreault is CTO.

The remaining core members, Lukas Bentel and Wiesner, are co-Chief Creative Officers, though when asked about those titles, they both laughed. “I don’t know what any of these [acronyms] mean!” Bentel said from a graffiti-covered room off MSCHF’s office in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint.

The two men, both in their early 30s, met while enrolled in a dual degree program at Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Bentel studied furniture design and electronic music; Wiesner, industrial design and materials engineering. They’re candid and chatty, a vibe that doesn’t quite square with the sense of mystery and aloofness that surrounds their collective.

MSCHF now has around 30 employees whose backgrounds range from design and art to marketing and tech. “It’s a good meshing of people who have a desire to create things with real artistic intent and other people who are trying to push it into a more real-world space,” explained Bentel. “A lot of the work that we make comes from that tension.”

MSCHF’s Satan Shoes (2021). Courtesy of MSCHF.

Being a business on paper has no doubt helped ease some aspects of MSCHF’s modus operandi. The group, for one, has been sued on numerous occasions. Last year, Nike accused MSCHF of trademark infringement after the release of “Satan Shoes.” Bentel, Wiesner, and co. ultimately agreed to recall the sneakers.

But their business savvy shows elsewhere, too. The group’s cannily marketed drops are now almost as anticipated as those from Balenciaga and Supreme. Their products usually sell out immediately, and it’s not uncommon to see them on eBay hours after they’ve been released.

At Perrotin, more than 350 individual artworks will be up for sale, each priced from $25 to $150,000. Some quick math shows that both the group and the gallery stand to make a good amount of money. (MSCHF said they have a “standard” agreement with Perrotin, typically a 50-50 split.)

The group’s blatant embrace of the commercial could make them easy to dismiss. But it also drives the central tension in their work. MSCHF not only participates in, but also exploits and profits from, the very systems they critique: vapid hype cycles and publicity stunts, the general machinery of commerce.

Call it hypocrisy. It is. But in repeating that cycle of hypocrisy, they instantiate a kind of joke to which many of us in these the desultory days of late capitalism can relate: money is evil, but if someone’s going to make some, it might as well be me.

“It is in MSCHF’s nature to participate, even when we are critiquing or satirizing,” said Wiesner. “We’re looking at the places where commerce gets funky and wanting to abuse or intervene. We want our intervention to hit the exact same people who are living there in the first place.”

MSCHF, Axe Number Censored (2021). Courtesy of MSCHF.

“I love that they are taking an obvious risk in making something,” said curator Michael Darling, who wrote an introductory text for “No More Tears, I’m Lovin’ It.” (Darling, like Perrotin, has a soft spot for art in touch with popular taste. In his previous role as chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, he oversaw blockbuster exhibitions by Murakami, David Bowie, and Virgil Abloh.) “When they put their money on the table to buy a Damien Hirst print and then chop it up and hope that they can sell it to pay themselves back, they’re putting something on the line. That feels risky.”

Darling is a fan of MSCHF’s, though he’s not sure the rest of his industry will board the bandwagon.

“Sometimes the art world just has a real knee-jerk reaction to people who push these kinds of buttons,” the curator said. “I’m sure there will be a lot of tsk tsk-ing.”

MSCHF’s members, for their part, have no preconceptions about how the show will be received. “The times that we thought, ‘Oh, this is how people will react,’ people have reacted in a completely different way,” said Bentel.

“We always wonder who is [going to show up],” Wiesner chimed in. “And it honestly always shocks us.”

“MSCHF: No More Tears, I’m Lovin’ It” is set to run November 3 through December 23 at Perrotin in New York.