The Burns Halperin Report

Museums Can, and Do, Talk About Race. Just Not Whiteness

What the furor over Philip Guston—and the demand for Black American superstar artists—tells us about performative progressivism

What the furor over Philip Guston—and the demand for Black American superstar artists—tells us about performative progressivism

Zoé Samudzi

It was just announced that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York would receive a gift of 96 paintings and 124 drawings of Philip Guston’s from the personal collection of his daughter, Musa Mayer—a collection spanning the entirety of his storied four-decade and multi-style career. The gift was made on the condition that the Met would permanently exhibit about a dozen of his works at any given time. While museums are often reluctant to accept gifts with these curatorial caveats, the Met’s director, Max Hollein, eagerly claimed the prospect of being the premier institutional custodian of “one of the important artistic figures of the 20th century.”

The gift is, no doubt, a sensational acquisition of the oeuvre of a path-charting artist whose experimentation and disregard for convention has produced a constellation of (belated) admirers and aesthetic successors. But there remains a deep dissonance between the celebration of this “provocative artist” and the institutional anxieties around—really, a profound inability and refusal to contend with—the political themes in this work beyond easy ascriptions of “anti-racism.”

Considering how the hullaballoo around the initial postponement of the Guston survey revolved heavily around his Ku Klux Klan paintings from the 1960s and ‘70s, the eventual and largely defanged presentation of the artist’s apparently self-evident “challenge” to whiteness was weakly taken up through the traveling exhibition’s failure to robustly contend with the very “anti-racism” they purported to appreciate about his work.

The first iteration of the exhibition failed to take seriously that Guston was not only standing in solidarity with Black people (as with his vandalized mural in support of the Scottsboro Boys or in the ominous lynching scene in Drawing for Conspirators, which he created as a teenager), he was also considering and confronting his own implicated positionality in white supremacy as a white Jewish man.

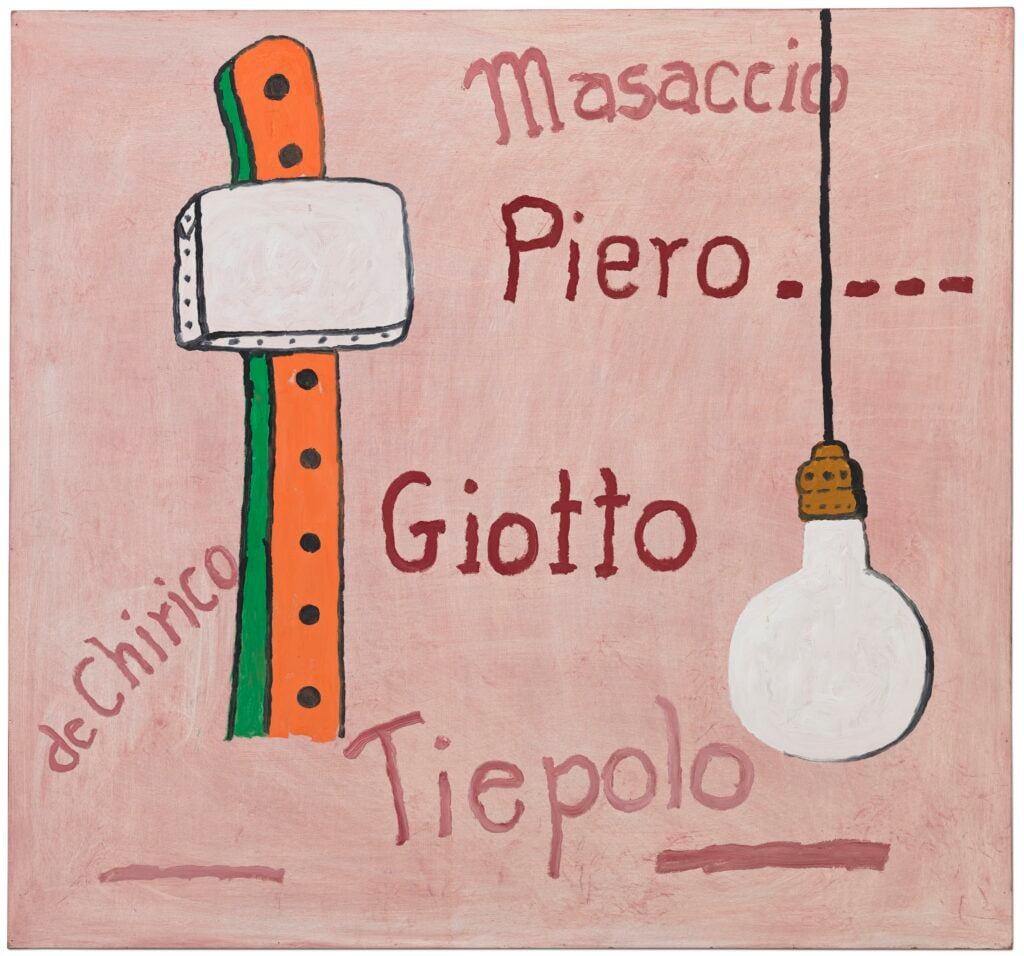

Philip Guston, The Line (1978). Photograph by Genevieve Hanson © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer

While museums have claimed an investment in “diversity and inclusion” as of late, this claim has really only translated into a fetishization of particular kinds of Black expression, falling painfully short of more far-reaching engagements of and with race. What lingered through the institutions’ inability to contend with simultaneous anti-Black and antisemitic terror vis-à-vis the KKK was a hackneyed deployment of platitudes that simply translated the urgent stakes of Guston’s mid-century challenges to whiteness and assimilability into palatable and inoffensive social justice museumspeak.

The primary dissonance lies in the celebration of the acquisition of works whose politics institutions have demonstrated they do not actually understand. Or, if they do understand them, museums are unable to engage properly because these ideas and their implications run completely counter to the political economy of the exhibitionary complexes of the gallery and museum. In conjoining “the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, [and] the mystique of the experimental laboratory…to produce a unique chamber of esthetics,” the continued existence of the white cube form within the colonial museum is made possible by the stabilizing force of racial capitalism (and its alienating aesthetics of display), not its deconstruction or dismantling.

Anecdotally, there feels like something of a racial divide in the Guston fandom. Beyond people who do appreciate the dynamism of his politics and genre-spanning work, cynically, I think white (and male) admiration for Guston comes from the way his Klan paintings challenge normative proprietary claims about which identities can represent certain experiences or violences. If Guston, a white man, could make art about anti-Black lynchings, what else ceases to be off limits?

Will the Met be any more able to actually engage the artist’s “deeply philosophical approaches to the nature of artistic identity” in the forthcoming special installation opening of the gift from his daughter at the same time museums are so hamstrung by their fear of openly admitting to the social, political, and material dynamics that animate their spaces? Guston’s provocation raises exciting aesthetic-political considerations, but the discursive lag—the apparent inability for art museums to contend with the questions of subjectivity that Guston was presenting as many as 90 years ago—illustrates the art world’s obsession with particular kinds of racial representation coupled with an existential fear of contending with whiteness.

Philip Guston, Pantheon (1973). Photograph by Genevieve Hanson © The Estate of Philip Guston. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Promised Gift of Musa Guston Mayer

Through its quantification of raced and gendered statistics in museum acquisitions, this third iteration of the Burns Halperin Report undercuts the performed progressive optimism about the diversification of the mainstream art world. In a game of word association, “transformation” would be paired with “inertia”—museum collections look nothing like their publics, a word laden with qualifications and caveats.

Using data from the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study of England and Wales, we can interpolate the results from a newly published paper in Sociology that troublingly concludes that “while those from more privileged social backgrounds have long dominated [in the art world], there has been no change in the relative class mobility chances of gaining access to creative work.”

While the contours of British class society are undeniably different from the United States, the exclusionary and often insular nature of art endures across geographies, and class critically inflects institutional relations with race and gender. One particularly illustrative example is in the production of and financial investment in Black art superstars.

Despite breathless commitment to diversity and inclusion, acquisitions of Black art peaked in 2015, just two years after the genesis of the Black Lives Matter movement. Seventeen of the top 20 female artists are white; the remaining three are Yayoi Kusama, Julie Mehretu, and the late Frida Kahlo. In specifically considering Black American women artists (i.e. Black women artists born and/or based in the United States), the top five—Mehretu, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Mickalene Thomas, Amy Sherald, and Alma Thomas—collectively comprise 60 percent of the auction market for all Black American women, approximately $124 million in auction sales.

Auctioneer Oliver Barker at Sotheby’s in May 2017 auctioning of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (1982). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Zooming out to Black American artists (which is overwhelmingly to say, Black men), the report disturbingly notes that “the top five Black American artists at auction account for 83.5 percent of the total market for all Black American artists.” Just three of the top 20 artists are women: once again, Mehretu, Crosby, and Thomas. And if we excise the late Jean-Michel Basquiat, the unsurprising and long-exploited Black bestseller, the market expenditure from 2008 to the first half of 2022 drops staggeringly from $3.6 billion to $1.04 billion.

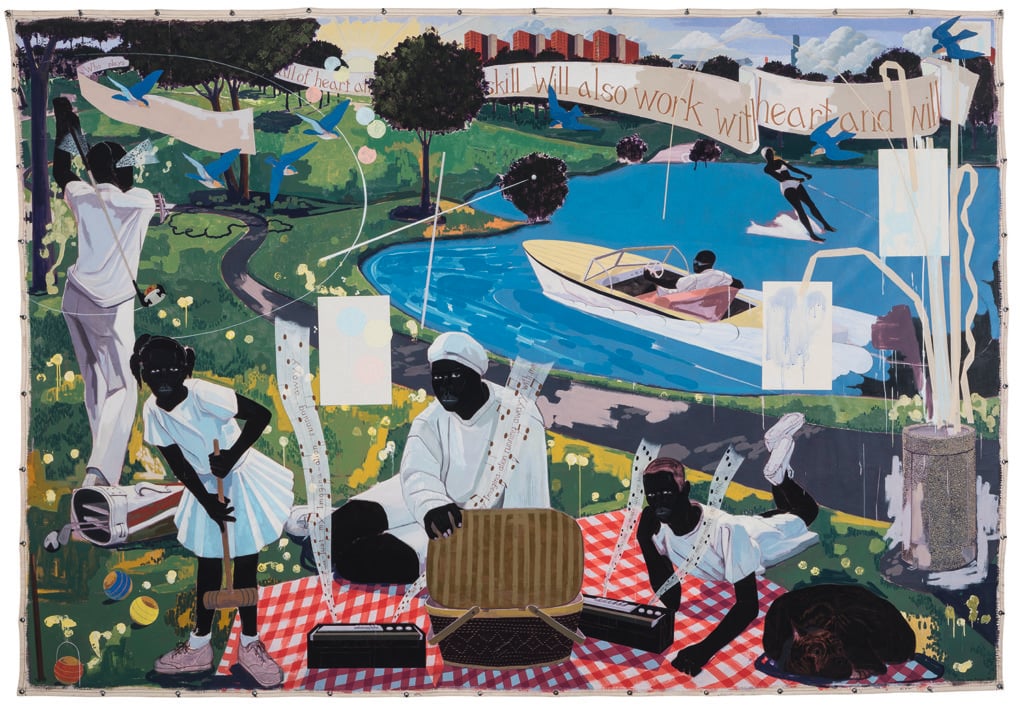

Following Basquiat, the artists Mark Bradford and Kerry James Marshall account for $194 million and $114 million, respectively, of this $3.6 billion total. Of particular interest are Marshall’s two top-selling pieces Past Times (1997) and Vignette 19 (2014), which, in 2018 and 2019, sold for $21 million (the highest auction price for a living Black American artist and quadruple Marshall’s previous auction record) and nearly $14.5 million, respectively.

One can’t help but grimace at the common descriptive language that Sotheby’s uses for the works, and how the artistic value of Marshall’s work is conservatively interpreted through a grammar of orthodox canonicity and mastery. Past Times is “an extraordinary visual feat that positions Marshall’s singular vision in dialogue with the masters of art history” and “confidently reclaims the presence of figures of African descent in the canon of Western art”; whereas Vignette 19 is “the supreme embodiment of the artist’s unparalleled renegotiation of the Western art historical canon” that “demonstrates the glaring absence of black figures from the history of Western painting” in its blackened interpretation of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Progress of Love: The Meeting (1771–73).

Kerry James Marshall, Past Times (1997). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

In the first pages of John Berger’s classic Ways of Seeing, Berger introduces the notion of mystification, which he describes as definitively asserted assumptions about truth, beauty, taste, and genius that are “no longer in accord with the world as it is” and further obscure rather than clarify history (as well as the present and future). If, paraphrasing Berger, an image is given meaning through intertextual relation with institutional definitions of these artistic qualities, the institution also mystifies the materialities of art-making. Superficial racial representation and the celebration of a handful of market-dominating collectible superstars and younger up-and-comers supplants any meaningful engagement with the barriers for entry into art-making and the sustenance of a career in the arts.

Through this mystification, artists (and, indeed, institutional staffers) are not workers, but rather creatives far removed from the means of production and whose alienated labor mystifies the kinds of exploitative industry stratifications that make an art world possible. Per historical trend, blackness is commodity to be possessed by any means necessary. But beneath the touted veneer of diversity and inclusion endures the protected core of racial capital. Black art enjoys its ongoing moment (especially post-2020); whiteness as economic structure, art-mystifying affect, and rationale for gatekeeping is both conspicuously absented and ubiquitous; and the transgressive Guston, who did in the 1930s and 1960s and 1970s what museums “still cannot,” remains a mystery.

Zoé Samudzi is assistant professor of photography at the Rhode Island School of Design.

You can read all the articles in the 2022 Burns Halperin Report here.