We think: maybe having more works by non-white artists in the collections of our art museums would equal fewer race problems among us, or would solve something. Including work in our museums by artists who are not straight, white, able-bodied, educated, American, men, or whatever—as long as the work is beautiful or masterful in accordance with the practices of generations of those men we say we no longer defer to; as long as the work is included sparingly up to, say, matching the demographics of the U.S. population; as long as the new artists are described mostly in terms of their difference from the old ones, so their inclusion always points back to itself and reminds us that we did them a favor—this is a form of justice we can all get behind. Right?

Art museums are not going to give us solutions to their problems that are not based on collecting and displaying art. They are (I say this without sympathy) doing the best they can. But comparing the demographics of our collections to our population is insufficient, given some pretty basic historical facts.

Native American populations have been more than decimated by the violence of U.S. policy. Would it be enough to have works by Native American artists comprise two percent of art collections that would not have existed in a world where Native American peoples and cultures had not been systematically eliminated?

Just 1,877 works by Black women were acquired by the surveyed museums between 2008 and 2020—0.5 percent of all their acquisitions in that period. Millions of Black people died during the Middle Passage and enslavement and afterward, and today Black culture is readily sanitized and capitalized for white audiences. Surely these facts merit more than a 6.6 percent share for Black women.

Obsessions with Blackness and femininity and queerness and more have moved the white male imagination to give us much of what western culture is—even if we don’t interpret it that way. Identity is too complex a concept and representation too meager a strategy for demography alone to be a suitable metric of systemic museum change. The survey even juxtaposes museum acquisition numbers with auction prices, as if the usefulness of both is equal. The artist gets nothing from auction sales. Market share doesn’t equal personhood. (Sojourner Truth: Ain’t I blue chip?)

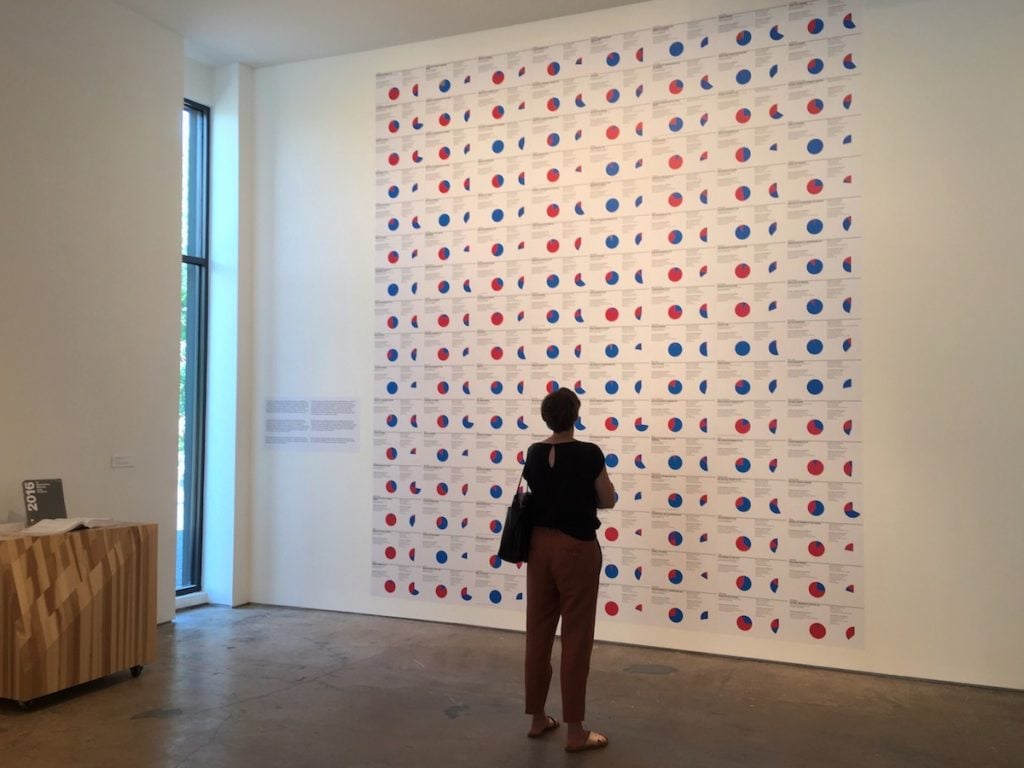

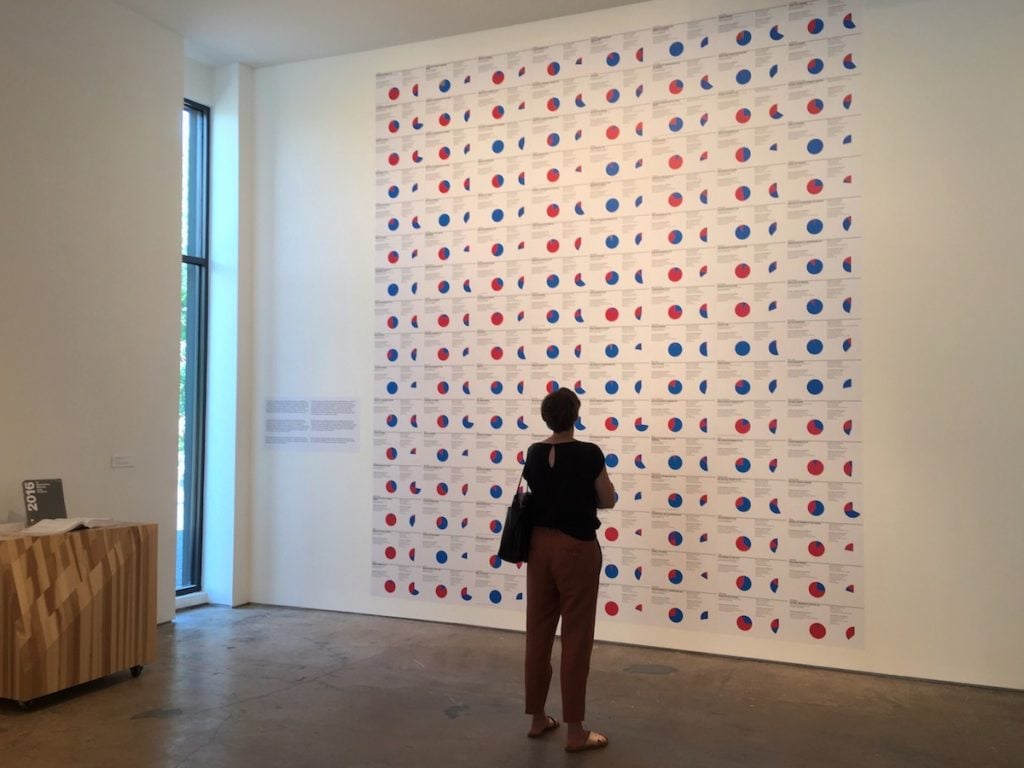

Installation view of Andrea Fraser, documenting the political contributions of board members of U.S. museums. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

If you think 1,877 is a small number, try this: 1,760. That is the number, give or take a few, of the board members at the museums surveyed by the Burns Halperin Report. 0.000538 percent of the U.S. population. The premise of this survey—of all the surveys, of the organizations and grant-funded initiatives looking to “diversify” museum boards with more, different-looking rich people or with non-rich people subsidized by rich people—is that this is the way it should be, that decisions on what to hold for the sake of humanity (what does that mean) should rightfully be made according to the tastes of so few.

As fellow contributor to this report Nizan Shaked describes in Museums and Wealth: The Politics of Contemporary Art Collections, many collectors use art museums to juice the value of their personal collections, then sell them. Shaked theorizes that the value of art in the museum is socially constructed by an attentive public. The public is the rationale and the engine for the museum’s generation of untold private capital gains. Gaps in the collection are a boon for the scheme. Failure to diversify museum collections is a problem where the breathless solution is ever more failure. What could a capitalist love more than a moral imperative to make more money?

In all the op-eds about museums’ relevance to the public, I’ve never seen an author describe the art museum as what it is: a place where we can see quite clearly how the U.S. government has privatized the work of the public good, and what that has wrought. Museums are no better than the world. They are inextricably relevant to the situation we’re in.

In the art museum, artworks are prioritized over people. According to a report by AFSCME Culture Workers United, six of the museums represented in this survey—the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the MCA Chicago, the Seattle Art Museum, the Toledo Museum of Art, and MOCA L.A.—received publicly funded Paycheck Protection Program loans intended to keep workers employed during the Covid-19 pandemic. Each of these museums later reported employing fewer workers. The museums had to turn to public money, using PPP loans until they ran out and then letting their workers go so they could collect unemployment. Where were the boards and other donors then?

Protest by Brooklyn Museum workers in front of the museum. Photo by Ben Davis.

Brooklyn, Cleveland, MCA Chicago, and MOCA collect at rates above the national average in all the categories measured in the survey. All of these surveyed museums undoubtedly collect works by Black artists at rates multiple times greater than in previous years. At the same time, the Mellon Foundation’s 2022 Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey found that public-facing and building operations workers, the positions that were cut most frequently between 2018 and 2022, were held by people of color more often than all other positions in the museum.

(I was corrected by spokespeople for Cleveland, Seattle, Toledo, MCA, and MOCA when I labeled their worker losses “layoffs.” Each situation was slightly different, but all of them said, first and foremost, that calling all of the losses “layoffs” was misleading. These over here were furloughs, they collectively said, and these other ones were voluntary departures. Only a few were layoffs. I realized that “furlough” is a term of intent, not impact—a furlough can’t be called a temporary loss, as much as we want it to be so, until it’s over. From the worker’s perspective, an indeterminate furlough is a layoff. Mellon’s report gives museums credit for improving their hiring diversity in public-facing positions. It makes no comment on whether these positions remain more precarious than others. We’ll find out next time the museums get nervous.)

What I’ve appreciated about the union organizing at museums in the past couple of years is that at the very least, unions stir up conversations about labor practices and class within institutions that tend to avoid them. Museums talk a lot about race and gender, with caveats: not with white male artists, not regarding our staff, and only so long as these concepts are politically inert.

Unions, more than the media, art criticism, and other means of institutional critique I’ve seen, have revealed to the public through organizing in recent years that institutions, rather than being monoliths, actually host power struggles among departments and between employer and employee. During the Philadelphia Museum of Art union strike, the museum posted collections images on Instagram through clenched teeth while the union, the Roadrunner, ran circles. It posted from the picket line, broke the story that the museum had retained an anti-union law firm, argued to a union-friendly city that upholding the public trust meant being a good employer—and won.

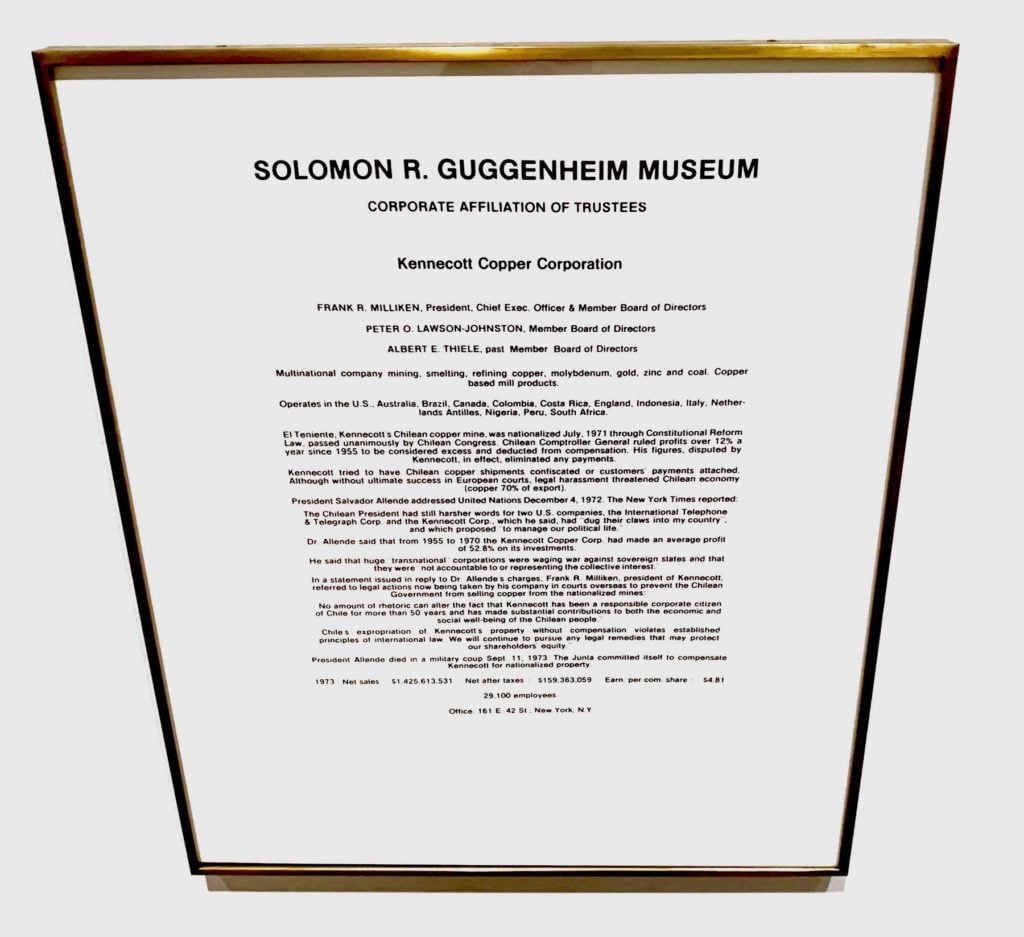

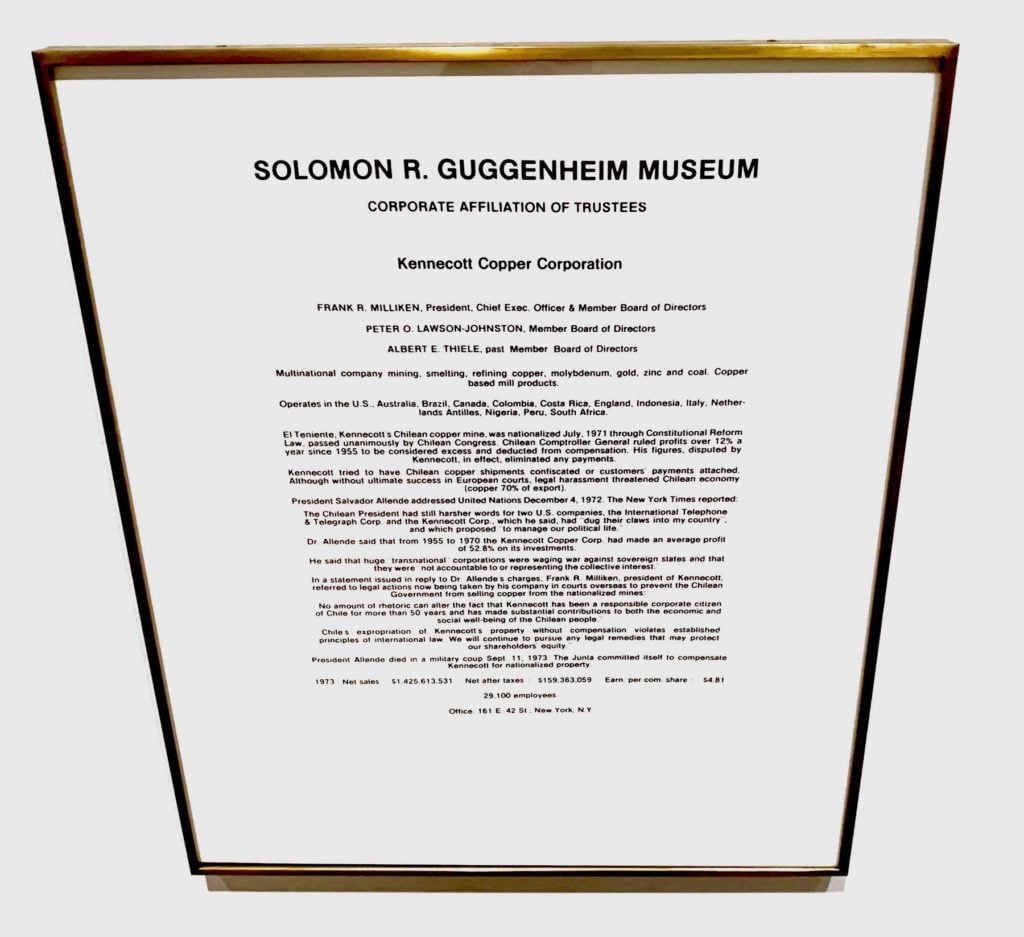

Panel from Hans Haacke, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Board of Trustees (1974). Image: Ben Davis.

I’d like to see more of that, everywhere. Blow the whistle, steal documents and post them on the internet, follow the donors’ money where it goes and publish, publish.

The power is the thing, not the paintings. It is the power that must be challenged. Unions do that internally, to the degree that it’s possible, by organizing people to claim and wield their labor as power. There are other ways to make counter-institutions: artist co-ops and galleries, anti-profit bookstores, art lending at libraries, quilting circles, braiding circles, apartment salons, citywide political education tours. Conversations. Not everything needs a grant. Not everything has to scale.

There’s this, paraphrased and true. I asked my friend Malik once, “What do you think it would take to sue a museum?”

“For what?” he said.

“For abusing the public trust. For not being sufficiently public.”

“If they do that, they’re illegitimate. Suing assumes legitimacy.”

You know? Just walk away. Being essential, art is irrepressible, ubiquitous. Museum walls keep more art out than in. So why keep the walls? The ceiling of our desires should be higher: a democratic and more richly public world of art.

Terence Washington is a writer who works as the Manager of Civic Engagement and Programs at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

You can read all the articles in the 2022 Burns Halperin Report here.