Art World

7 Top Collectors Look Back on the Artworks That Got Them Hooked, From a Miró Print to a Warhol T-Shirt

Pamela Joyner, Jorge Pérez, and other collectors share stories on the works that started it all.

Pamela Joyner, Jorge Pérez, and other collectors share stories on the works that started it all.

Artnet News

![]() How does an art collection begin? We asked seven collectors to tell us the story of the work that started it all, and how their first acquisitions shaped their collecting habits for the future. Their influential early acquisitions range from an Aaron Young video to a lithograph purchased with winnings from dorm-room poker. Together, their stories reveal that art collecting is all about paying close attention—and being open to adventure.

How does an art collection begin? We asked seven collectors to tell us the story of the work that started it all, and how their first acquisitions shaped their collecting habits for the future. Their influential early acquisitions range from an Aaron Young video to a lithograph purchased with winnings from dorm-room poker. Together, their stories reveal that art collecting is all about paying close attention—and being open to adventure.

Julia Stoschek, via Twitter; a still from Aaron Young’s High Performance (2000), courtesy of MoMA.

The first piece of video art I purchased was High Performance (2000) by Aaron Young, back in 2004. At that point, he didn’t have a gallery and I was just starting out myself. It was a very special time for both of us. We met at MoMA PS1 in New York, and he showed me the work on his laptop. It was kind of a funny situation: I had never acquired a video, and he had never sold a video before—absolute beginners!

I am very happy to have this significant piece in my collection. His performances, sculptures, and videos often harbor moments of danger. By staging a precarious situation in the context of contemporary art, he questions how media, appropriation, action, and setting are used and how the public is included. In the video, filmed in San Francisco in the former studio of Diego Rivera, a motorcyclist does a burnout by letting his bike run in place.

In this creative, highly performative act, destructive action and generative power are combined in a confined space to form a threatening contradiction. Between high speed and groaning stasis, this media burnout also deals with new forms of painting and sculpture. This piece offers many ideas, something which fascinates me in regard to time-based media in general. It has a certain sense of synesthesia and different modes of perception; it is a video, a performance, a sculpture, and a painting all at once.

My wife Laura and I started collecting photo-based art when we married in 1991. We both loved photography and it seemed like an affordable way to start a collection. Our collecting was sporadic and impulsive for the first several years without any particular direction and without investing a lot of money. I think the turning point came in 1998 when we bought a seascape by Hiroshi Sugimoto: Bay of Sagami, Atami, 1997.

This was a breakthrough for us for several reasons. First because we had met the artist and had a deeper understanding of who he was and what his practice was about. Since then, our relationships with artists have become an important part of our interest in collecting. The second thing that was new was the sticker shock. This was not a casual purchase at the time; it felt much more like an investment. Of course, that print is now worth far more than what we bought it for. Finally, this was the first picture that we acquired that was conceptual, driven by an idea, rather than an image. Indeed, at first glance, it appears to be nothing. But of course, this beautiful image of fog obscuring the sky, the horizon, and only faintly revealing the ripple of water in the foreground is a picture of everything.

Pamela Joyner; Norman Lewis, Afternoon (1969). Collection of Pamela Joyner. The Art Institute of Chicago. Photo courtesy of Scott & Co.

The first Norman Lewis work I bought—Easter Rehearsal (1959)—changed the way we collect. That decision made me question deeply how such a talented artist who influenced and inspired a generation of artists succeeding him could be so thoroughly overlooked by formal art history. That contemplation has framed the whole way we now approach the collection.

Jorge Pérez, photo courtesy of Sergi Alexander /Getty Images; Joan Miró lithograph, courtesy of Jorge Pérez.

Perhaps it’s not a “major” artwork, but my first acquisition was a Joan Miró lithograph while I was in college. It cost me $100 and I still have it in my office! I grew up visiting art museums in Bogotá and Buenos Aires with my mother, which led me to develop a love for art and artists. This passion came with me when I moved to the US, but I was a broke college student and couldn’t afford to buy any artwork of my own. Shortly thereafter, I realized I had a knack for dorm-room poker, and as soon as I made some money, I went out and started collecting. With my first few payouts, I bought works by Miró, Marino Marini, and Man Ray.

That first work opened up the world of collecting to me and helped me realize that art was a perfect way to explore and come to understand foreign cultures. Over time, my views evolved and I began to see art as a way to explore my own heritage. This desire to look inwards and explore my roots deeply impacted my interests as a collector and led me to focus primarily on artists from Cuba, Colombia, Argentina, and other Latin countries. The effects of that first lithograph can most definitely still be seen in my current personal and corporate collections.

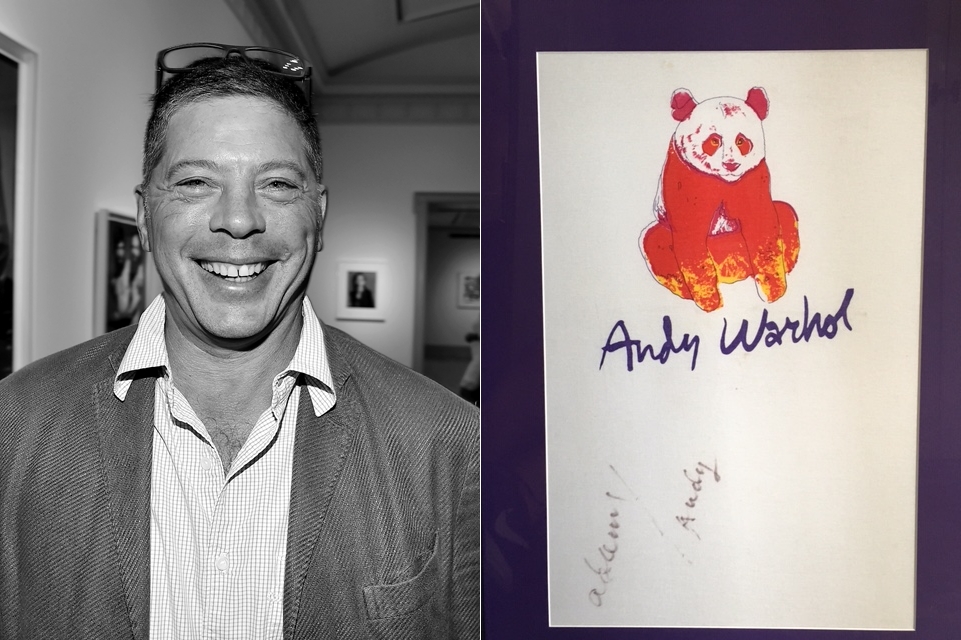

Adam Lindemann, © Patrick McMullan; signed Andy Warhol t-shirt, courtesy of Adam Lindemann.

My first work was a signed t-shirt from Andy Warhol. He gave it to me for my birthday in 1984 and I remember being so disappointed and wishing he would have done something else, like sign a Cracker Jack box, which is what he did for my brother, George Jr. I did around that time buy some big Statue of Liberty paintings on board from Victor Hugo, but I used those to cover my law school apartment windows then I just forgot about them.

The Warhol t-shirt ended up in the back of my old drawer at my parents’ house. Years later, it reappeared as my mother was changing my childhood room into an office. She said, “I found an old t-shirt that says ‘Andy Warhol.’ Do you want it?” I jumped, got it, and framed it. It’s a panda from the “Endangered Species” series and it’s signed Adam/Andy—that’s all. I’ve hung it somewhere at home ever since. Right now, it’s in the kitchen in Montauk. Market value? Zero, but it’s not for sale—it’s a keeper.

Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Only Connect (2000). Courtesy of Robert and Nicky Wilson.

Robert and I began collecting for Jupiter Artland in 2001, but previously we always had an interest in collecting on a more individual basis. Paintings are entirely Robert’s domain; I am a sculptress, so that is my realm. Before we bought the property, we had been collecting work by local artists—Scottish paintings—but we changed from buying small paintings to searching for the right kind of thing in the landscape—what is influenced by the land and refers to the land.

I gave Robert a sculpture, a small stone carving, by Ian Hamilton Findlay. It is still in our kitchen, and that work sparked a narrative within us that has bled into landform and conceptual works of art. The seed of Findlay’s environmental ethos has been very influential.

Robbie Antonio, courtesy of Nadine Johnson; Andy Warhol’s Camouflage (1986), © 2017 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.