There was no question-and-answer period after the premiere of Madeleine Sackler’s film It’s a Hard Truth Ain’t It at the Tribeca Film Festival this past spring. Rumors swirled that it had to do with a particularly unhappy audience member sitting near the back: Nan Goldin. The celebrated photographer has been after the filmmaker’s—and the whole Sackler dynasty’s—attention in order to hold them accountable for their role in the opioid epidemic.

The Sacklers have an outsize influence in art-world philanthropy, and their name graces museums worldwide. But some of the family’s fantastic wealth has been bolstered by Purdue Pharma, founded in 1892 by brothers Raymond and Mortimer Sackler. (Their older brother, Arthur Sackler, held stocks in the company until his death.) The company created and marketed the highly addictive painkiller Oxycontin, which is at the heart of the ongoing opioid crisis in the US.

Goldin herself was addicted to the drug for years. Until now, the company (and most of the Sacklers) have largely kept quiet about the escalating epidemic. Goldin first condemned the Sacklers in an op-ed in Artforum in January and has also launched the activist group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). In the span of eight months, PAIN has shown up unannounced at the Met, the Harvard Art Museums, and the Smithsonian to stage protests and “die-ins.” In April, she spoke about her movement before the US Senate in Washington, DC.

Goldin was recognized at the film screening and escorted out by security, who told her they knew she was carrying empty pill bottles, which she and her group are known to scatter at protests. But this remains her new strategy: show up and make noise until she is heard. We spoke with the artist about her new political activism, the importance of “showing up,” and the art world’s trouble with speaking out against dark money.

Nan Goldin Speaking at a protest at the Met. Photo: Michael Quinn.

There has been some pushback from members from Arthur Sackler’s side of the family, including his daughter Elizabeth Sackler, claiming that they have been unfairly blamed for their relatives’ business. Do you make a differentiation now between the three Sackler brothers—Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond—and their respective children?

We have heard repeatedly from Arthur’s widow, Dame Jillian Sackler, and Elizabeth that because Arthur died before the existence of Oxycontin, they didn’t benefit from it. But he was the architect of the advertising model used so effectively to push the drug. He also turned Valium into the first million-dollar drug. And a similar drug, MS Contin, was released while he was alive, which was only a few molecules away from Oxycontin. The brothers made billions on the bodies of hundreds of thousands. There are now 175 people dying a day. The whole Sackler clan is evil.

Has the Sackler family reached out to you in the six months since you launched PAIN?

Only after I published the piece in Artforum, where I talked about the family but didn’t make a differentiation between Elizabeth Sackler and the rest of the family. She wrote a letter to me through Artforum, and they published that as well as my response to her.

Purdue has repeatedly asked to meet with me through the press, which seemed like a waste of time because I don’t feel they have anything to say. They would just use it as a PR statement, and they would try to divert everything and talk about the need for more police.

However, PAIN is considering arranging to speak to some of the members of the family directly, including Elizabeth Sackler. She made a statement at the beginning that she finds what Purdue is doing heinous and that she is completely separated from that. She wrote that she supports and admires me for speaking about my story and taking action, so we want to ask her to be our ally. I asked her that in my response to her letter, but I want to take that up again.

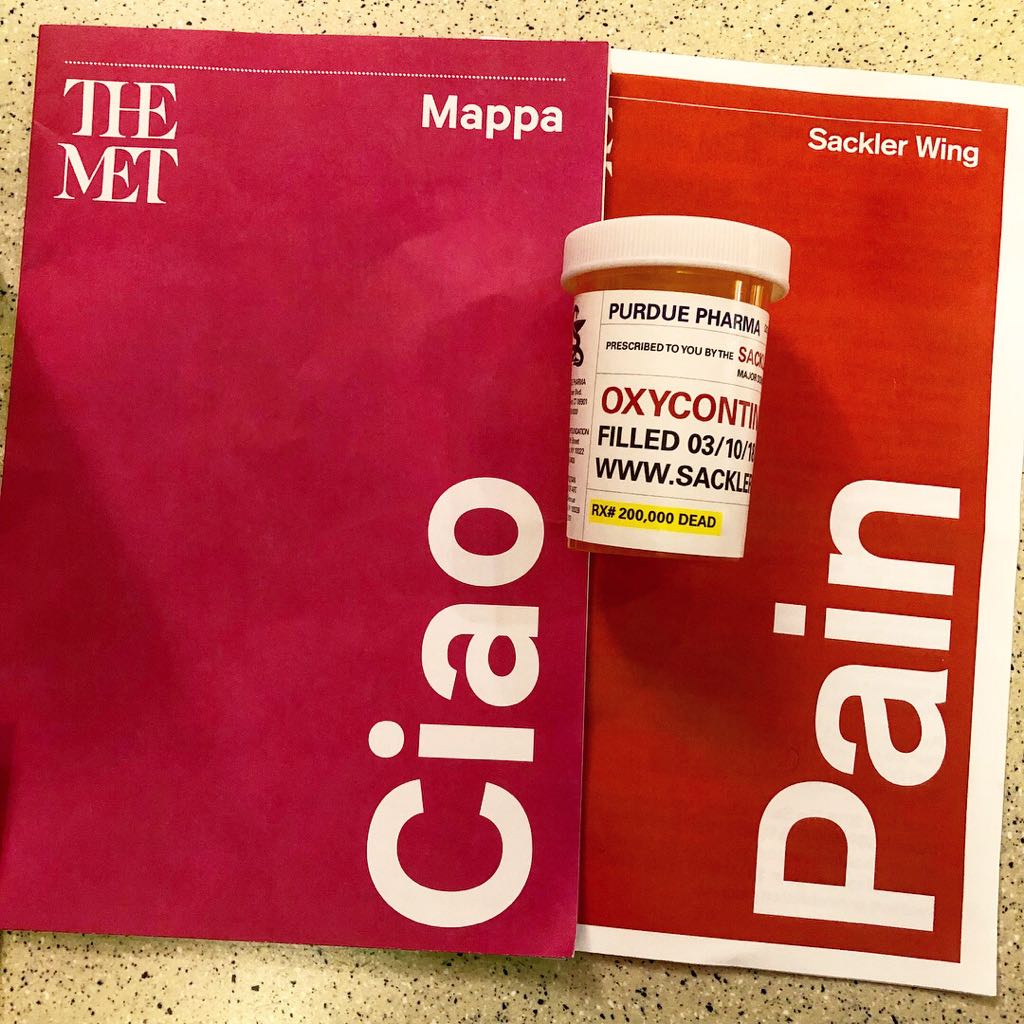

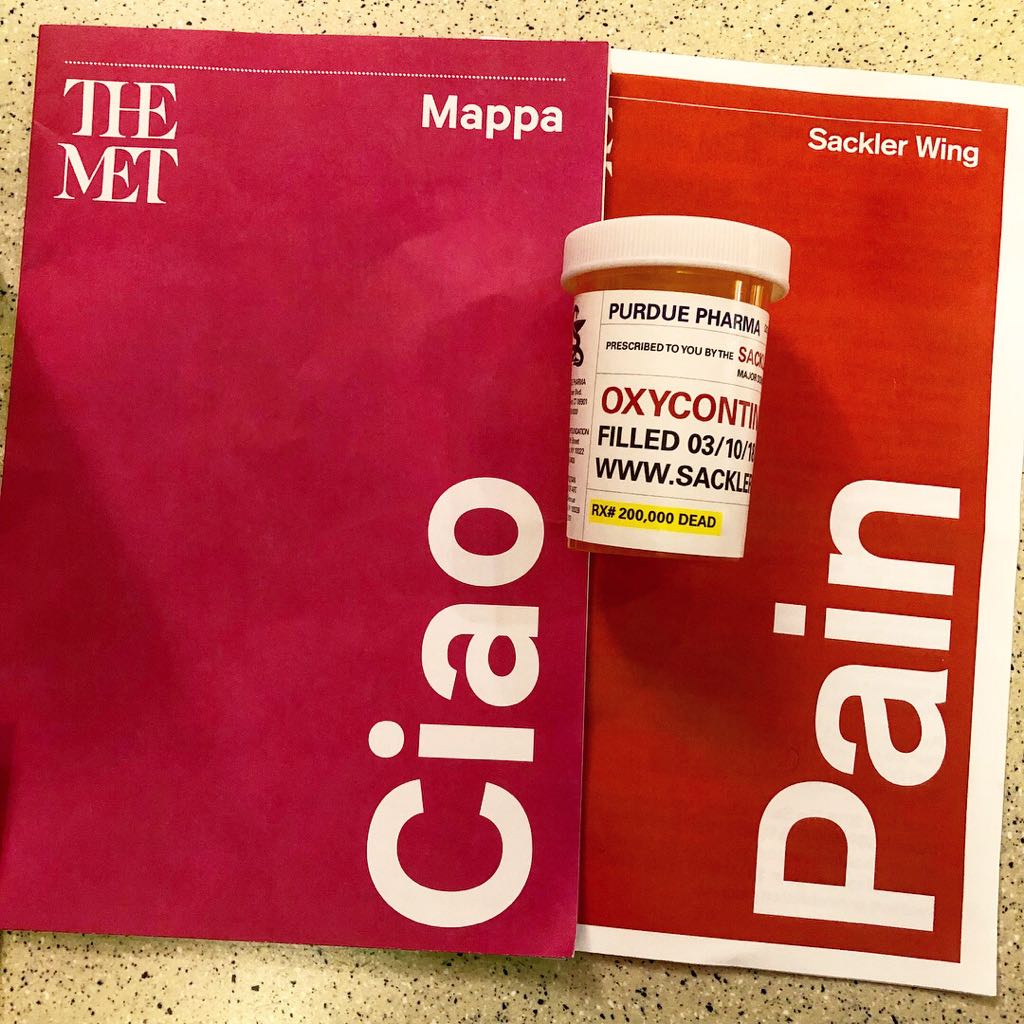

PAIN Bottle. Photo: Thomas Pavia

Have any museums or directors come out to support your group?

No. They haven’t responded. I have close allies at the Whitney Museum—they were the first to buy the Ballad of Sexual Dependency in 1991, and they have a big collection of my work. I said, “You’re having this show of political art and here—right in front of you—one of your artists is doing political work, so why don’t you stand up for me?” They said it’s because they don’t have money from the Sacklers, but that’s irrelevant. That gives you a perfect platform to speak up and support. Privately, they tell me they support PAIN, but they don’t go public about it.

Why do you think they don’t speak up?

Our group is based on direct action, guerrilla tactics, and showing up without warning. That makes people nervous since they never know where we are going to show up. Everybody has their own interests and it’s surprising how much Sackler money is out there—even the Louvre has a Sackler wing. The Louvre and the Met are my favorite museums in the world, and both have big money from the Sacklers.

Does it trouble you when you think about some of the collections you are in?

I think about the museums I am in and their collections, though I don’t think any Sacklers have personally bought my work—or any of the other evil millionaires and billionaires for that matter. I don’t think my collector base is on that level, fortunately.

Were you surprised by the subdued reaction from art institutions?

It’s hard to shock me. The world is run by greed. I grew up with David Wojnarowicz, and he warned me in the 1980s that museums were controlled by their board members. At that time, there were no shows about the lives that we lived—about gays, women, minorities. People fought that battle and won. Whether there is any substance behind these shows, in terms of real life, is questionable. But I always knew that board members did control the museums, so I am not surprised by any of it, but it doesn’t affect my belief in making and showing art. Not that I would show in a Sackler wing.

PAIN bottles and pamphlets. Photo: Noemi Bonazzi

How do you compare this current fight with your work addressing the AIDS crisis in the 1980s? Are they similar?

Yes, absolutely. ACT UP is the model for our group. It began in someone’s living room, like my group, and it spread all over the world. Without ACT UP there wouldn’t be prevention for AIDS now. They were successful, and meanwhile many of them died. I was close to ACT UP, but not close enough. I went to demonstrations, but I didn’t get as directly involved as I wish I had. It was only through my work. This time, I want to be on the forefront of activity. But I was very close to Wojnarowicz, and he told me that the people in ACT UP supported my work, which is really significant to me. Our bottles are starting to become emblematic of the cause, like the Silence=Death logo of ACT UP.

I never feel like I am doing enough on the ground, but at least because I have a voice I am able to scream about things and be heard. The important people are the ones running safe-consumption sites, but I can be a voice for them because I have the ear of the media.

Has your belief in the impact and urgency of art faltered in any way since you’ve become involved with PAIN?

Not at all. Art is a survival mechanism. I still believe that art is holy and speaks in a psychological, spiritual, and ethical language, as well as an aesthetic one. I know art can change lives. For instance, I know my work has helped gay people to come out. When the Ballad was published, a number of people told me that it made them move to New York to escape America. That’s political.

ACT UP members recently protested the Whitney Museum’s David Wojnarowicz show because they felt it treated the ongoing AIDS crisis as a resolved chapter in history. What was your reaction to that?

I think there should have been a demonstration in support of the show. I don’t understand why it would be protested when David’s work is some of the most profound and articulate art about AIDS ever made. The existence of the show brings the crisis to the forefront from its beginnings. If it doesn’t seem relevant to the on-going crisis now, it’s because David is dead. But David probably would have appreciated the protest for itself.

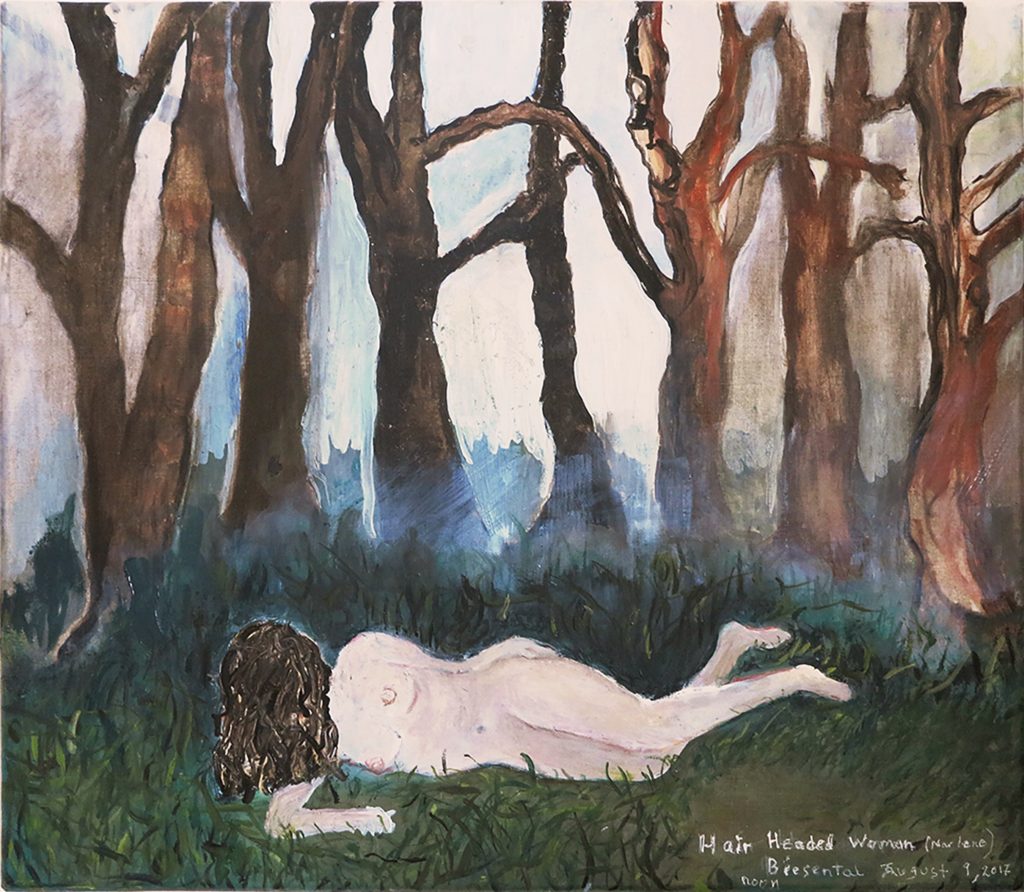

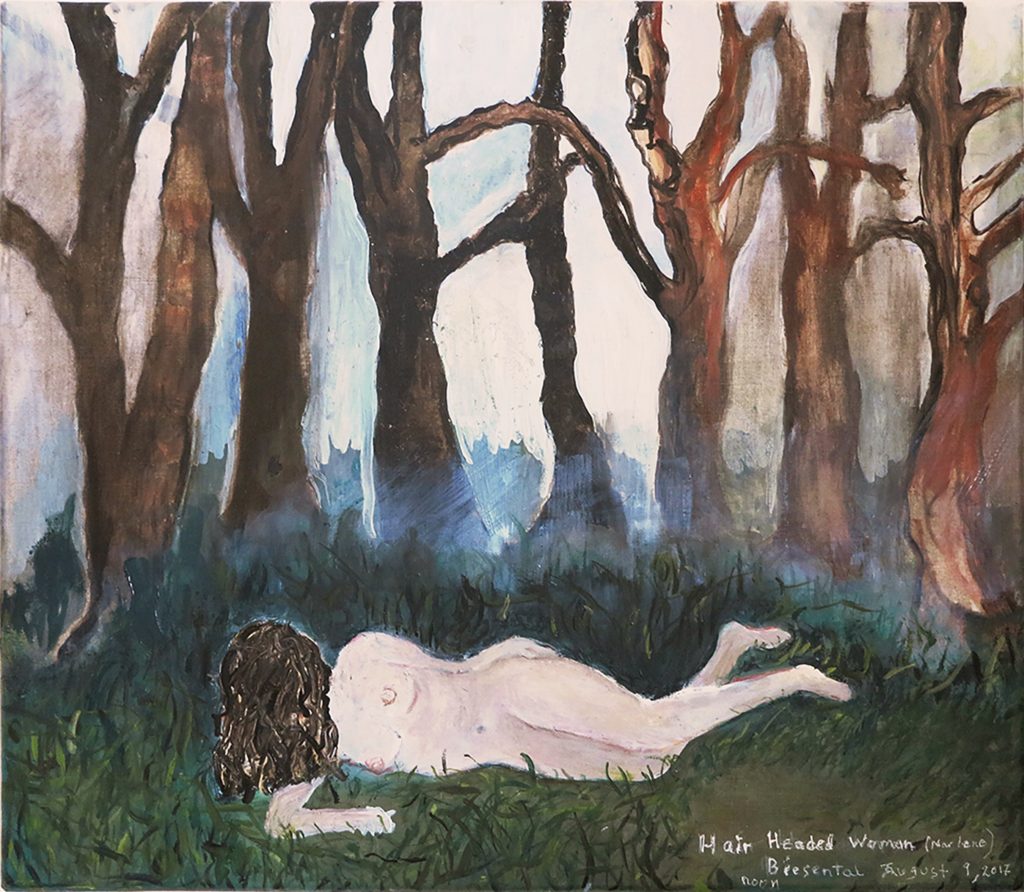

Nan Goldin’s Hair Headed Woman, Biesenthal, August 9, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

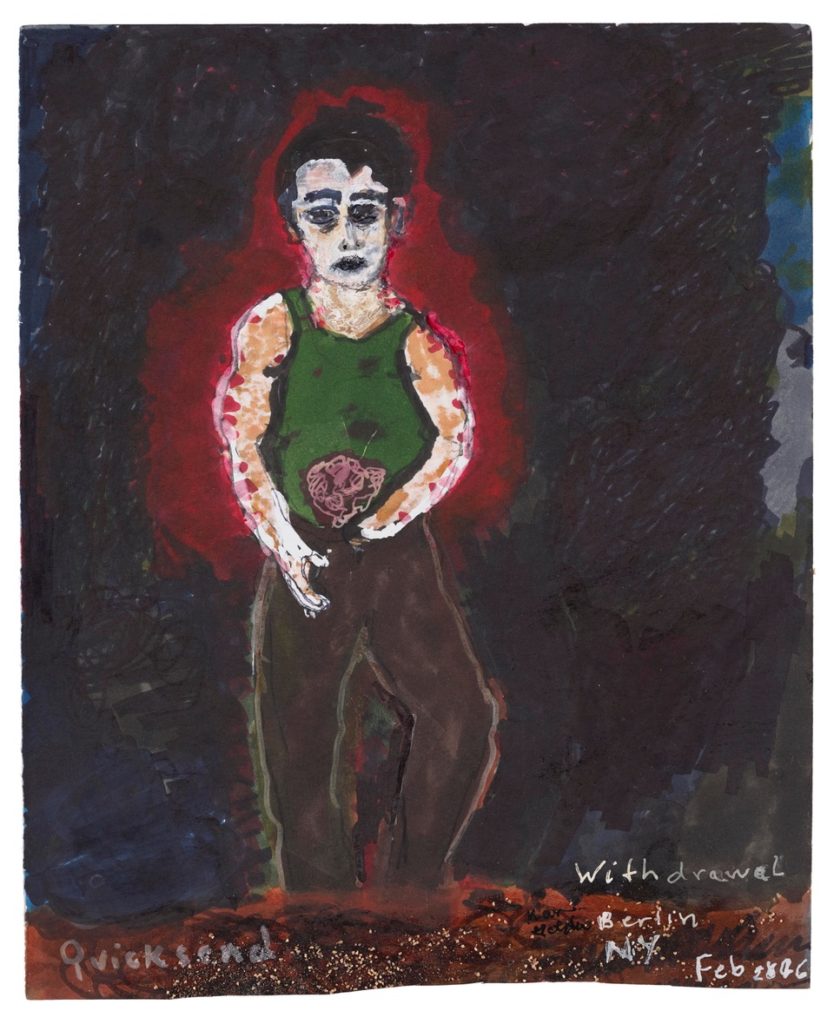

I understand that painting is a more recent, and lesser known, part of your practice. How does it connect to the chronology of your addiction and recovery?

I drew my whole life. I dropped out of everything to go to art classes. I had an art teacher when I was 13 who said that someday I would be in the MoMA. And I was, though not for drawing.

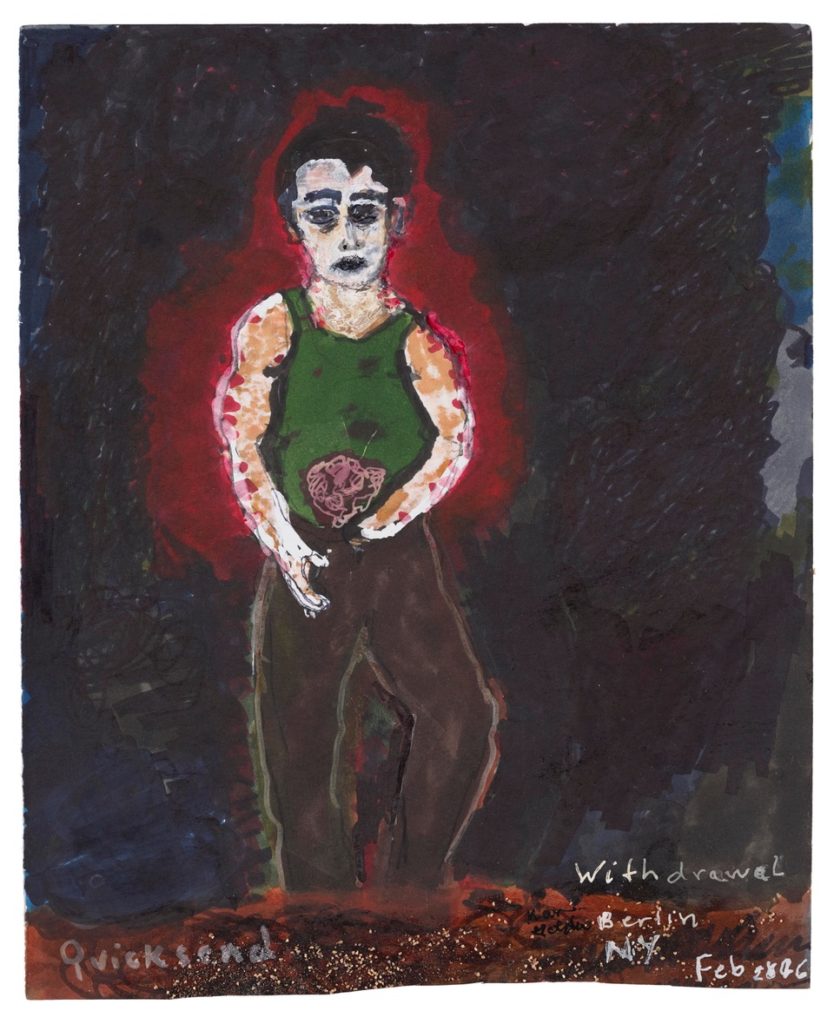

Starting in about 2013 or 2014 drawing became my diary, and throughout my whole addiction to Oxycontin, the drawings I was making kept me alive. The drawings that I did when I was high—well, I can’t access the same part of my brain now that I’m clean and sober. So I am painting now, but out of a different part of my brain. It’s not as easy, but they are better, technically, and more careful. I don’t have that freedom I had when I was addicted.

How do your drawings and paintings differ from your photography?

When you draw there’s nothing between you and the paper. It’s one of the purest forms of art—putting your hand to paper. There’s no distance. I would just put my hand on the paper and it would draw itself. I wouldn’t decide what to draw. It was very intense and magical.

I did a few paintings directly from people. They don’t look like the people. It’s about you and the paper, and there is no issue of expression between you and the person and what the person expects, like there is in photography. It’s just you and your process.

I haven’t photographed that much in recent years. In general, I haven’t photographed like I used to. I did more drawings and paintings than I made pictures, because I was very isolated.

Nan Goldin’s Withdrawal/Quicksand (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

What do you think is the difference between activism that involves physically showing up and online efforts?

There is a word for that: clicktivism. People stay home and click. I believe direct action is our only hope. Our last action at Harvard had about 75 people. Ironically, there are pictures of mine in an exhibition there by a friend who gave his whole collection to the Fogg Museum. It gives me more legitimacy when speaking about the Fogg. I also used to work there in the late 1980s and I love this museum, but now it has an Arthur Sackler wing. That felt particularly bad to me.

The Harvard students wanted to do an action so they reached out to us and we all came together and threw bottles and there was a lot of chanting and signs. They let us stay an hour and a half, and when we spoke to the guards on the way out, they said they agreed with us. They said, “Come back anytime.”

Bottles floating in Washington, DC. Photo: TW Collins.

What’s next for you and PAIN? Do you have any plans to protest at the Louvre?

We’re staying in America for now. The problem is in Europe, too, but it’s not anywhere near the magnitude that it’s been in America. Purdue has cut back their sales force and they ran a big advertisement in the Wall Street Journal last week supposedly meeting our demands, though not mentioning us. They co-opted our language and our petition and claimed they are doing all the things we are asking for. Now we are going to demand to see whether they are doing it and how much money they are putting behind it. But they have done so much damage that, even if they cut off Oxycontin, the damage is done. We need them to be accountable.

Learn more about P.A.I.N. here.