Art World

Nan Goldin Takes Her Anti-Opioid Protest to the Smithsonian—and the Senate—in Washington, DC

The photographer lent her support to new legislation that would dedicate $100 billion to battle the opioid crisis.

The photographer lent her support to new legislation that would dedicate $100 billion to battle the opioid crisis.

Caroline Goldstein &

Julia Halperin

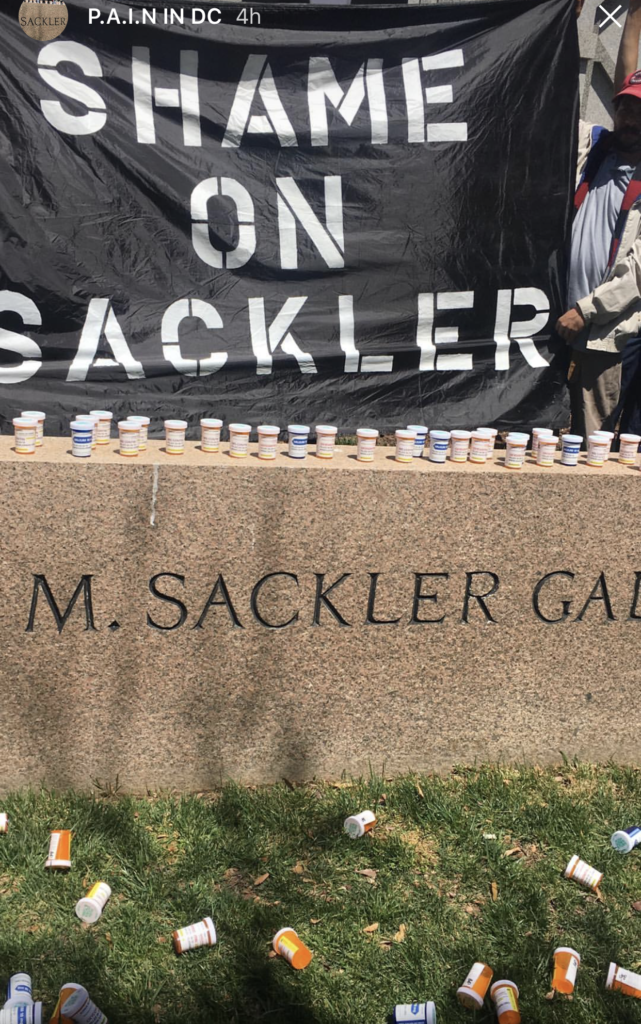

The photographer Nan Goldin led a sprawling demonstration at the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC, on Thursday. Dozens of protesters streamed into the building carrying signs reading “Shame on Sackler” before filling the museum’s fountain and stairwell with empty pill bottles.

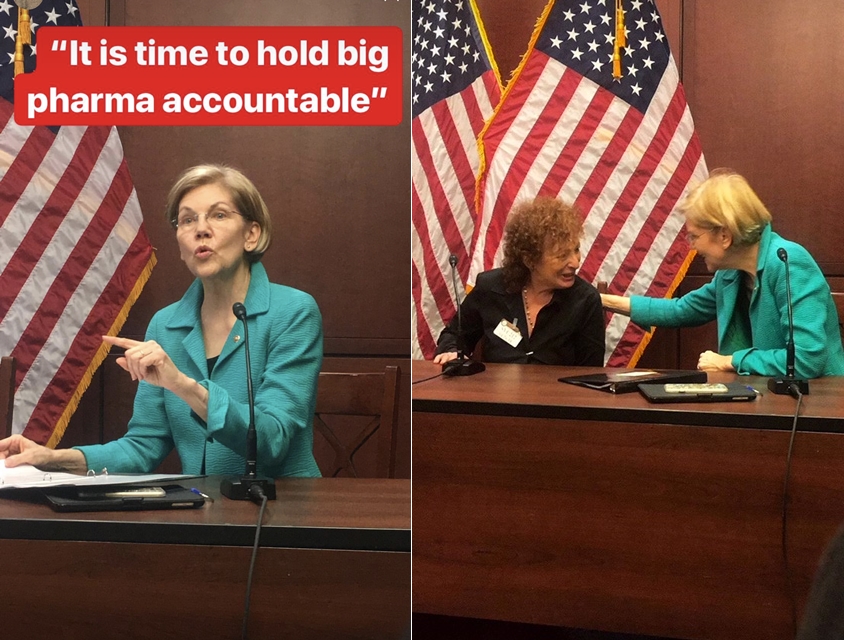

It was a busy day in DC for Goldin, who has emerged as a vocal advocate for anti-opioid groups and a strong opponent of the Sackler family, the prominent art patrons who founded Purdue Pharma, the company behind the painkiller Oxycontin. In addition to the Sackler Gallery protest, she spoke at a press conference held by Senators Elizabeth Warren and Elijah Cummings, who are co-sponsoring legislation that would allocate $100 billion to the opioid crisis over the next 10 years. The minority leader of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, also attended the event.

Warren and Cummings introduced the bill earlier this month. It is modeled on a bipartisan bill passed in 1990 aimed at targeting the AIDS epidemic—another issue that strikes close to home for Goldin, whose deeply intimate photographs helped put a human face to the millions who died from the disease, including many of her closest friends.

In her speech on Capitol Hill on Thursday, Goldin said her experience with the AIDS epidemic has motivated her to act now. “Everyone, it [AIDS] wiped out everyone,” she said. “And I can’t afford to lose another generation… It’s time to start treating the sources of that pain, before we lose more people.”

The new legislation would provide $1.8 billion a year to public health surveillance and $2.7 billion to the counties and cities hit hardest by the epidemic. It would also allocate $500 million a year to increase access to an opioid overdose reversal drug.

Senator Elizabeth Warren and Nan Goldin in Washington, DC on April 26, 2018. Images via Instagram @P.A.I.N. Prescription Addiction Intervention Now.

Goldin organized the Smithsonian protest with Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (P.A.I.N.), the advocacy group she founded at the beginning of the year, and the left-leaning advocacy group Center for Popular Democracy. Around 100 protesters rallied outside of the museum, according to a representative for Goldin. Many are recovering addicts who had traveled from around the country to participate.

A representative for the Smithsonian said that the protest was orderly and security officers stayed off to the side, and that with recent protests at other Sackler-named locations, Thursday’s demonstration was not a surprise. The Smithsonian also noted that the eponymous donation was made in 1982, Oxycontin was not introduced to Purdue Pharma until 1995.

This is not the first time Goldin has brought her fight to cultural institutions’ front doors. In March, she staged her first public protest inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Sackler Wing, scattering pill bottles in the fountain next to the Temple of Dendur.

The night before traveling to DC, Goldin also attended a screening of It’s a Hard Truth, Ain’t It, a documentary directed by Madeleine Sackler at the Tribeca Film Festival. Filmed entirely within the Pendleton Correctional Facility in Indiana, the documentary was the product of a workshop involving 13 incarcerated men, who starred in and co-directed the film. The majority of the participants described suffering through a multi-generational cycle of drug abuse and addiction.

An Instagram post by the poet and author Nick Flynn, who attended the screening.

Goldin hoped to confront the director during a post-screening Q&A session to highlight the connection between addiction and incarceration. But the audience was not permitted to ask questions and security knew that Nan and her team were in the audience. Immediately following the presentation, guards ushered viewers out, at one point raising their voices at Goldin and insisting she exit.

“We see your pill bottles,” one guard said. “We know what you’re doing.” After the screening, Goldin approached audience members individually to share her message. “The security here is way more intense than at the Met,” she told artnet News.

Madeleine Sackler is the granddaughter of Purdue Pharma co-founder Raymond Sackler; her father, Jonathan, is a Purdue director. Earlier this year, a New Yorker article considered whether Sackler’s family ties should inform the reception of her activism. It is a question that many institutions (with far more degrees of separation) have begun to grapple with as the public outcry around the opioid crisis grows.

In the January issue of Artforum, Goldin revealed that she had become addicted to Oxycontin after having been prescribed the drug while recovering from wrist surgery. Since then, her group P.A.I.N. has taken to Twitter and Instagram, using the hashtag #ShameonSackler to share facts about the crisis and raise awareness about the family’s extensive philanthropic ties.

The P.A.I.N. protest at the Smithsonian’s Freer Sackler Galleries. Images via Instagram @P.A.I.N. Prescription Addiction Intervention Now.

Descendants of Arthur M. Sackler, the Smithsonian gallery’s eponymous donor, have said they did not benefit directly from the sale of Oxycontin. (Arthur’s brothers, Mortimer and Raymond, purchased his shares in Purdue well before the drug was developed.) Goldin, meanwhile, has maintained that Arthur Sackler should not be entirely absolved because he developed marketing strategies that Purdue later used to great effect to distribute the drug.

A representative for Jillian Sackler, Arthur’s widow, has said: “Passing judgment on Arthur’s life’s work through the lens of the opioid crisis some 30 years after his death is a gross injustice. It denies the many important contributions he made working to improve world health and to build cultural bridges between peoples.” The representative did not immediately respond to a request for further comment by the time of publishing.