Today marked the beginning of the third and reportedly final week of the Knoedler forgery trial, which is taking place at US District Court in Lower Manhattan. The morning started with surprising news, reported by the New York Times, that former Knoedler and Company president and central defendant Ann Freedman had suddenly reached a settlement with plaintiffs Domenico and Eleanor De Sole over the weekend.

Not surprisingly, the terms of the settlement were confidential. The De Soles are seeking up to $25 million in damages for a fake black-and-red Mark Rothko painting they bought for $8.3 million in December 2004. As media and observers of the case were attempting to make sense of the Freedman news, the trial, which continues against the now-shuttered Knoedler gallery, started with business as usual.

Presiding Judge Paul Gardephe began this morning’s proceedings by informing the jury that the De Soles and Ann Freedman “entered into an agreement” over the weekend, and instructed the jury to “not speculate as to the terms of that agreement.” He added that Freedman will still testify in the case since the information is central to her “state of mind” and “intent” during the years when the gallery sold dozens of forged Abstract Expressionist-style paintings.

The left side of the room—where just two Knoedler defense attorneys sat today—was a marked contrast to the past two weeks, where a swarm of attorneys, including Freedman’s lawyer Luke Nikas, sat conferring during the trial. This morning Freedman was absent, and Nikas left shortly after Judge Gardephe commenced his comments. However, Freedman is expected to take the witness stand this week.

The morning was consumed almost entirely by presentation of videotaped deposition of art historian and paid Knoedler consultant E.A. Carmean Jr. Portions of Carmean’s testimony, which focused heavily on the purported connection between art dealer David Herbert and the mysterious—and nonexistent—buyer referred to at the gallery as Mr. X, who originally bought all these works directly from the artists, were presented first by the plaintiffs and then by the defense, though major portions of what was presented overlapped.

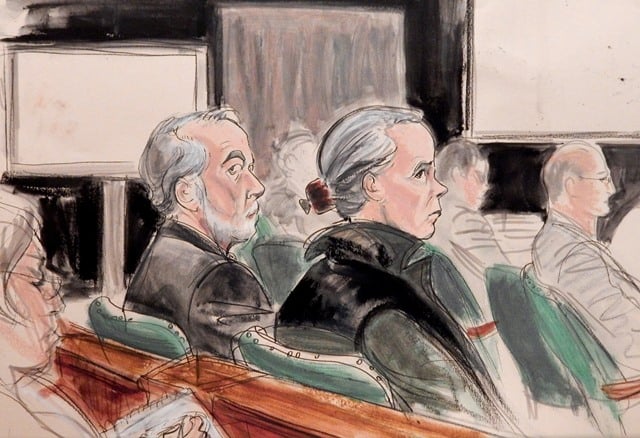

A painting sold by Knoedler as a Mark Rothko that turned out to be fake.

Carmean, whose testimony first began airing this past Friday, commented on the “logic” of saying that Herbert had been the “connector” between the paintings and Mr. X, despite his never uncovering any firm or written evidence of this link, which he had been hired to research. Unlike most other experts who have appeared on the witness stand so far and distanced themselves from any suggestion of having supported or authenticated the works, despite the gallery’s having said they did so, Carmean did not recant his prior agreement with the story that Herbert had been involved in assembling the collection.

The art historian used the analogy of a baseball team when discussing Betty Parsons Gallery and Sidney Janis Gallery, theorizing which players or coaches might have had connections to both. Carmean then brought up the example of Herbert guiding a collector named Jinny Wright to Rothko, even though the artist was not represented at Sidney Janis Gallery, where Herbert worked at the time.

At one point Carmean was questioned as to whether he had “ever given any consideration to the possibility that the information was false.”

Carmean responsed that he was “not sure,” adding, “If a painting looks like the real McCoy, so to speak, you ask ‘How did this object come to get here?'”

Questioned about what he meant by the term “the real McCoy,” Carmean employed several music-related analogies, telling the attorney if he was to play five records—of which four were an Elvis impersonator and one was Elvis himself—”you’d probably be able to pick out Elvis.” He also employed the hypothetical scenario of encountering a relative at an airport, specifically his own mother-in-law, saying, “it’s just that there is a familiarity to an overall presence.”

Carmean did concede at one point that the inclusion of Herbert’s name on the provenance of so many works “should have always been said with a question mark.”

In other noteworthy parts of his lengthy testimony, Carmean admitted to being paid about $5,000 a month, first by Knoedler, and later by Freedman, stating, “I wasn’t in the business of authentication. Let’s be clear about that.” He also insisted that he was never aware of the price of individual works, since that was not his concern as part of his “curatorial” efforts.

The afternoon session kicked off with testimony from Rothko expert and National Gallery of Art curator Laila Nasr, who has worked on both the Rothko paintings catalogue raisonné as well as on the Rothko works on paper catalogue raisonné, the latter of which is still in progress. Nasr corresponded with Freedman over one of the fake Rothkos and subsequently included it in a show.

She was first questioned by the De Soles’ attorney Emily Reisbaum, who repeatedly introduced correspondence between Nasr and Freedman, asking whether the form of the letters or information contained therein was unusual. Amid several objections from the defense—some of which the judge sustained—Reisbaum persisted in asking questions about language contained in letters such as that noting a Rothko work “that made its first public debut at Knoedler and Company at last winter’s art fair in New York.”

This is presumably a reference to the Art Dealers Association of America’s (ADAA) annual art show at the Park Avenue Armory. Under questioning from Reisbaum, Nasr conceded that such language had been the result of “several requests from Ann Freedman.”

Like other experts, Nasr said she relied on Freedman and Knoedler’s impeccable reputations in believing that the work was indeed a genuine Rothko.

During cross examination, Knoedler attorney Charles Schmerler asked Nasr detailed questions about what a catalogue raisonné entails, asked her whether forensic testing of paintings was available in 2002 (she replied no), and presented letters in which Nasr had praised one of the fake Rothko works, comparing it to the artist’s famous Seagram Building commission. About the work, Untitled (1956), Nasr wrote in one letter, “it is so grand without being large.”

Asked about the Seagram comparison by Schmerler, she responded that the comparison was on “a purely coloristic” basis and was the same as comparing two postcards and finding “a superficial resemblance.”

During the defense’s cross examination of Nasr, Schmerler also asked her about the 2002 ADAA art fair, when she visited the Knoedler gallery booth where the De Sole Rothko was on display. In addition to typical art fair literature, Nasr recalls that the gallery was touting a sheet with the names of various experts who had viewed the painting.

“I’m not even sure at what point I realized my name was on the list,” she told the jury. “It was an art fair and there was a lot of people and literature floating around. But I just remember walking away and thinking, ‘This is such an odd handout.’”

Nasr expressed discontentment with finding her name on the list, but admitted she never complained to Freedman or anyone else at the gallery. She noted that at the time, she had no idea either of the Rothko paintings she had seen at the gallery were fake, and would never have suspected as much based on the gallery’s stature.

“Ann Freedman and Knoedler gallery were very prominent in the New York scene and could have been a good resource. I didn’t want to alienate her,” Nasr admitted. “Everybody had trust in Knoedler gallery and in Ann Freedman.”

Nasr says she fell out of touch with Freedman and the gallery around 2005. However, in a letter to Freedman that same year shown during trial, she wrote: “Congratulations! I understand you have found a buyer for the Rothko Untitled (1956), which I was fortunate enough to view twice at Knoedler.”

Near the end of the day, Ruth Blankschen, the accountant for Knoedler from 1985–2001, briefly testified; she will take the stand again tomorrow.

—Additional reporting by Cait Munro