“I just want the truth,” said Charles Schmerler, an attorney for Knoedler & Company gallery, questioning art historian Jack Flam at US District Court in Lower Manhattan on Wednesday.

“I’m trying to tell you the truth!” Flam shot back. “But you seem resistant to it.”

The exchange came during three hours of testimony by Flam, the head of the Dedalus Foundation, devoted to Abstract Expressionist artist Robert Motherwell.

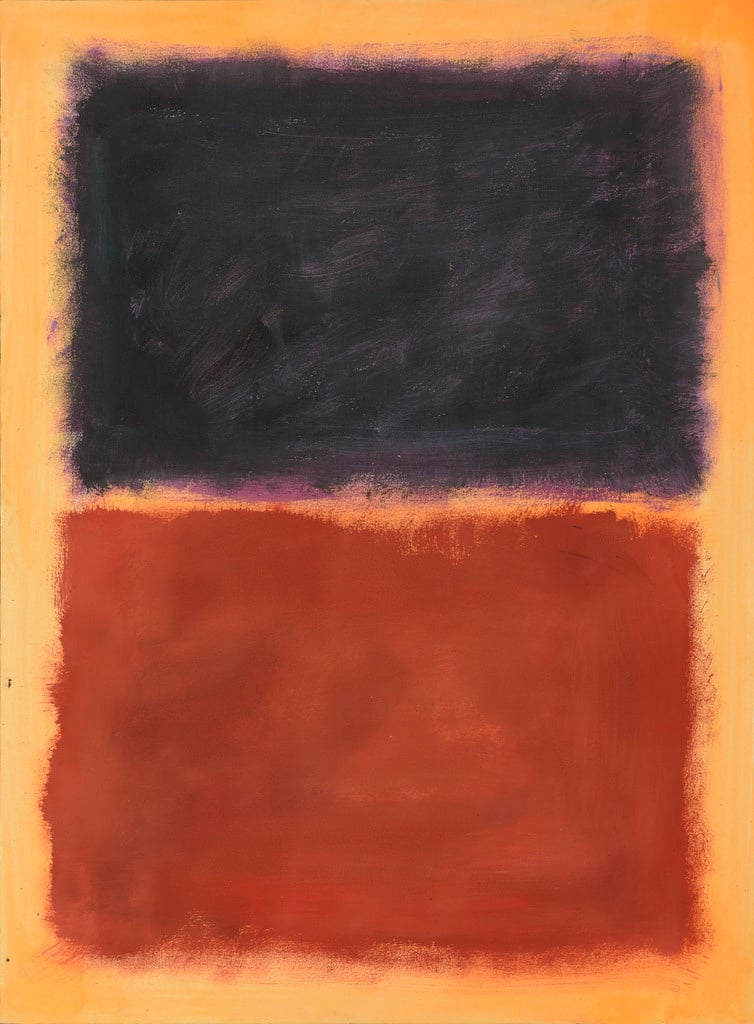

Forged Motherwell paintings were under discussion in the fraud trial of Knoedler gallery and its former director, Ann Freedman, who sold fake paintings by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and other artists that had been brought to the gallery by Long Island art dealer Glafira Rosales, who pleaded guilty to fraud in 2013 and is awaiting sentencing. The plaintiffs in the current case, Eleanore and Domenico De Sole, purchased a fake Rothko for more than $8 million from Freedman, who insists she was duped by Rosales. When their suit and others came to light, the gallery abruptly shuttered after 165 years in business.

Under discussion during the contentious exchange was a January 2006 visit to the gallery by Flam, during which he saw a fake Motherwell. Schmerler was drilling Flam on whether he was convinced by the painting when he first saw it, at which point Flam got testy, pointing out that he developed sufficient expertise to authenticate works only later, and that in any case, his original look in 2006 was only a casual viewing. He had no reason to believe it was fake when he first saw it, based on the gallery’s sterling reputation, he said.

Freedman would later indicate to potential buyers, in a document displayed in court, that Flam was one of a number of Mark Rothko experts who had authenticated a fake Rothko it was offering buyers. He is no authority on Rothko, he testified.

“If you’re going to list someone as an expert,” Flam said, “you should make sure they’re an expert first.”

Flam testified about what he called a “morphing” story with “lots of moving parts” that Freedman fed him about the source of the paintings. They had supposedly come from a secretive Swiss man who had a home in Mexico and whose collection had been “hermetically sealed,” she told him. Art dealer David Herbert had supposedly acted as the intermediary between Motherwell and the collector.

Flam said that in Freedman’s first telling, Herbert and the collector were friendly, then later that they were lovers. Motherwell had supposedly gone to Mexico in 1953, the date of one of the paintings in question. But Motherwell had not traveled to Mexico at that time, said Flam.

His conviction that it was fake deepened on investigation of the work.

The signatures, he said, were overly consistent, as though they had been copied from a template. The words “Spanish Elegy” were written on the back; Motherwell had never inscribed a work in that way, he said. He alleged that he told Freedman in no uncertain terms that the work was fake.

But Freedman insisted that the Herbert provenance was watertight, he said. She invoked Herbert so many times, he said, that it was as though it was meant as “a distraction.”

Flam then investigated the works at the studio of conservator Dana Cranmer (who had previously testified) and became only more convinced that they were phony, based on various physical characteristics such as the pristine quality of paint that was supposedly decades old.

“They looked more like the Elegies than the Elegies themselves,” Flam said, to laughter from the courtroom.

Forensic examination showed that bottom layers of paint included pigments that Motherwell didn’t use until later and that weren’t widely available when the paintings were supposedly done. In fact, the paintings allegedly exhibited smears of pigment that hadn’t been invented yet. One of the paintings was painted over an earlier painting that was sanded down, though Motherwell was known never to have sanded his canvases.

To all this, Freedman rebutted that perhaps someone else had signed or dated the paintings.

At the day’s end, veteran art dealer Martha V. Parrish, who helped draft a code of ethics for the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA), testified that when a dealer is offered an artwork at below market prices, she should be suspicious. If one work were offered at below market or without an established provenance, she said, you would want to investigate it. But if the dealer were offered a whole collection of works sharing those kinds of issues, then “you’re not going to touch it,” she said.

Faced with the sort of collection Rosales brought to Knoedler, Parrish said, “A reputable and responsible dealer would run like hell, because there are too many red flags flying for anyone to take the risk.”

Also testifying Wednesday were art historian Stephen Polcari, an expert hired by Knoedler who admitted Tuesday to an inability to tell two Rothkos apart, and Frank Del Deo, who succeeded Freedman as gallery director in 2009.

Additional reporting was provided by Sarah Cascone.