Galleries

8 Key Points to Know About the Knoedler Trial, Which Starts Today

A central defendant in the trial claims she is also a victim.

A central defendant in the trial claims she is also a victim.

Brian Boucher

The Knoedler forgery scandal rocked the art world in 2011.

Photo: artfcity.com

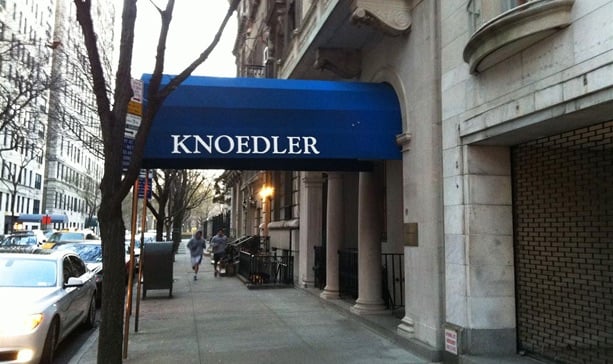

One of the most startling cases of fraud in art world history goes to trial Monday, January 25. Accusations of fraud led to the abrupt shuttering in 2011 of Knoedler & Company, an Upper East Side stalwart that dealt in modern and contemporary masters. The gallery, which allegedly sold dozens of fake paintings by Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock, had been in business since its founding in 1846.

“It’s amazing to think that this institution never stopped for 165 years,” former director Ann Freedman told Vanity Fair. “It didn’t stop during the Civil War, World War I, World War II.”

What world wars could not accomplish was accomplished by allegations of fraud covering the sale of dozens of paintings that sold for a total of over $60 million dollars.

Glafira Rosales.

1. The Alleged Masterminds

Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, his then girlfriend Glafira Rosales, and his brother Jesus Angel Bergantiños Diaz allegedly ordered up the fake paintings and fabricated the backstories, which often involved the paintings going straight from the artists’ studios to the collectors. Those collectors, because they supposedly wanted to guard their privacy, were referred to by names like Mr. X and Mr. X Jr., his son.

Rosales has pled guilty to the charges and is still awaiting sentencing. Both Diaz brothers were arrested in Spain and released on bail, but there is no word yet on whether they will be extradited to the US to face charges or to stand trial.

Former Knoedler Gallery president and director Ann Freedman has always maintained her innocence.

Photo: Patrick McMullen

2. Central Defendant—and Victim?

Knoedler director Ann Freedman is at the center of the case. She had left the gallery in 2009 after decades in the business. She bought some of the alleged forgeries, which lawyers say demonstrates her innocence, and which would make her a victim of the fraudsters as well.

Collector Domenico de Sole, who is now chairman of Sotheby’s board, is suing over a Mark Rothko painting that turned out to be fake.

Photo: Courtesy of Sothebys.com

3. The Plaintiffs

Bringing the case are collectors John Howard, who reportedly purchased a fake de Kooning, and Domenico de Sole, the former chairman of Gucci, who now serves on the board of Sotheby’s. De Sole and his family purchased a work, “Untitled, 1956,” which they believed to be by Mark Rothko for over $8 million.

4. The Settlements

Howard and De Sole’s case is just the one that has come to trial. Among the cases the gallery settled out of court are one brought by hedge fund manager Pierre LaGrange over a reportedly fake Jackson Pollock. That lawsuit has since been settled on undisclosed terms.

Another case brought by Howard, over a fake Willem de Kooning that he bought for $4 million, was also settled.

5. The Law

The plaintiffs have argued that the RICO (Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt Organizations) law should be brought to bear against the defendants. Written to combat organized crime, the law allows plaintiffs to triple their damages.

6. A central figure in the case will never take the stand

The alleged forger of the fraudulent paintings is Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese painter who lived in in Flushing, Queens, who has since fled the country and has reportedly taken up residence in China.

7. A misspelling of a famous artist’s name failed to raise red flags

The forger misspelled Jackson Pollock’s name in the signature of one of the paintings, writing it as “Pollok.” Even so, Freedman’s lawyers say she didn’t know there was a problem, arguing that she never would have paid $280,000 for the “Pollok” if she had known it was fraudulent.

8. What are the effects of the alleged fraud?

“The effects on those who might buy at art galleries and on the integrity of the New York art market overall cannot fully be measured,” John Howard’s attorney, John Cahill, wrote in an e-mail to artnet News.