When the National Museum of Scotland announced that a star object in its new galleries would be a rare original casing stone from the Great Pyramid, the Egyptian government was surprised. A row over its ownership, that echoes Greece’s longstanding claims to the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum in London, has put a damper on the celebrations of the Edinburgh museum’s 15-year-long £80 million ($104 million) transformation.

Egypt’s ministry of antiquities requested proof that the rare original casing stone of the Great Pyramid of Giza was not smuggled out of the country in the 19th century. The fragment, which has not been displayed before, forms the the centerpiece of the museum’s new Egyptian galleries, which open to the public today, February 8.

The museum robustly defends its legal title to the stone, the only example on display outside of Egypt, insisting that “the appropriate permissions were obtained when it was uncovered,” a museum spokeswoman tells artnet News. “The stone’s presence in Scotland since 1872 is fully documented,” she stressed.

Assistant Curator Dr Daniel Potter with a casing stone from the Great Pyramid. ©National Museums Scotland.

The embassy asked for proof of legal ownership, export certificates, as well as details about how the stone was removed from Egypt and the date it was obtained. The museum spokeswoman says that it supplied the embassy with “all the relevant information,” although the Guardian reports that the embassy had not received the documents on Wednesday.

“The current Egyptian law on the protection of effects criminalizes trafficking in effects,” a ministry of antiquities spokesperson told the Times. “They are not allowed to be exported and are considered public funds. If the mass or any other artifact were to be found removed illegally, all necessary action would be taken to recover it.”

The pyramid, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, was built for the Fourth Dynasty pharaoh, Khufu, and was completed in around 2560 BC. In the 19th century Scottish engineers uncovered the stone a pile of rubble from road building work at the base of the pyramid. It was brought to Scotland in 1872 at the request of the country’s Astronomer Royal, Charles Piazzi Smyth, and donated to the national museum in 1955.

Casing stone from the Great Pyramid. ©National Museums Scotland.

The Egyptian galleries are part of the latest phase of the modernization of the 19th-century museum. Additional revamped galleries are dedicated to East Asia and the Art of Ceramics. The renovation work has opened up space to display more of the rich national collection, which holds some 12,000 objects.

More than 1,300 objects will be on show in the new galleries, and the museum spokeswoman said that around 40 percent of these have not been displayed in “at least a generation, if ever. “

See some more of the objects going on show at the National Museum of Scotland below.

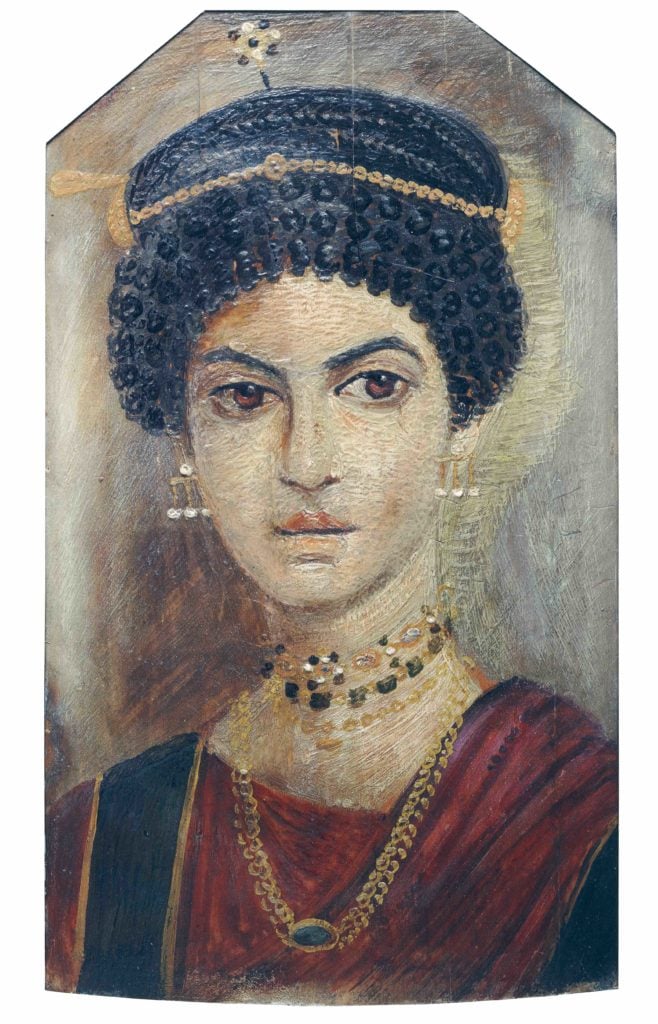

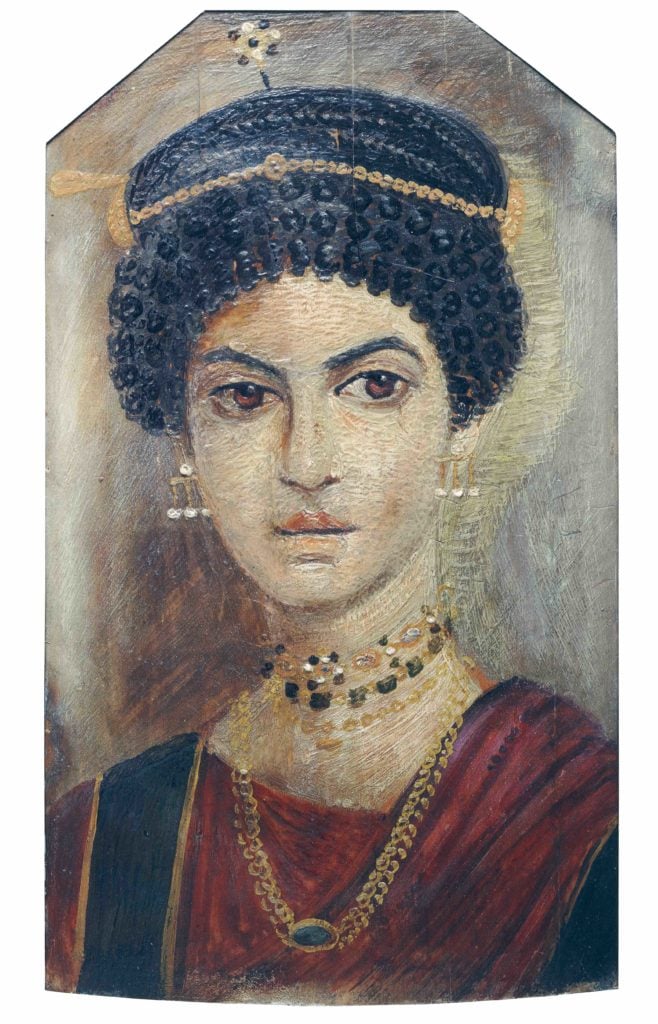

Mummy mask and shroud probably from Deir el-Bahri, Late Roman Period, 200-300 AD. Copyright National Museums Scotland.

Okimono of carved ivory, Daikoku pulling the tail of a cat, to keep it from harming his rats, unsigned Japan. Copyright National Museums Scotland.

Jug of ground flint and orange clay paste- Persia, late 15th century. Copyright National Museums Scotland.

Large vase depicting Chairman Mao with an inscription wishing him a long life (1968). Copyright National Museums Scotland.

Childrens’ coffin from Thebes, Roman Period. Copyright National Museums Scotland.