People

Nato Thompson Asks Whether We Can Weaponize Art and Culture for Good in a Post-Fact Era

What do public art and Starbucks have in common?

What do public art and Starbucks have in common?

Brian Boucher

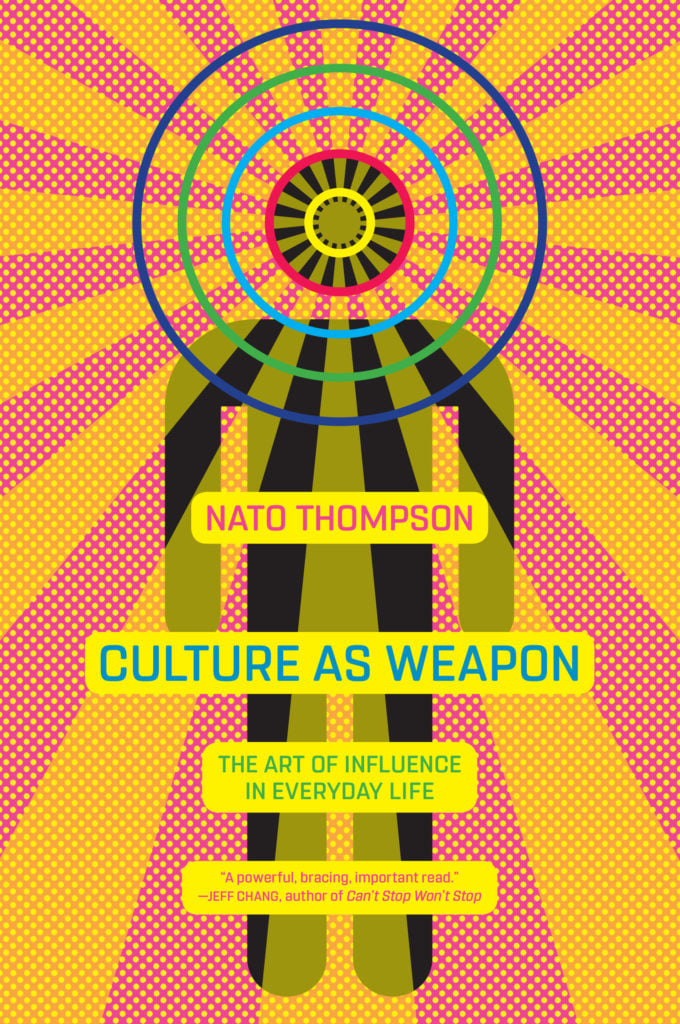

In his new book Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life, curator-author Nato Thompson outlines the ways that all forms of culture can be deployed to appeal to our emotional selves—more often than not appealing to our fears.

Gliding, in one example, from Mother Teresa’s use of soup as charity to Andy Warhol’s appropriation of the red-and-white Campbell’s Soup logo, Thompson then pivots to cause-related marketing; for example the soup company’s own boosting of its profits by turning its label pink to raise funds for breast cancer while also improving its bottom line.

In an even more troubling instance of the co-optation of cultural knowledge, Thompson describes the employment of anthropologists in the counter-insurgency effort in Iraq, and then turns to comparing both community organizing and socially-engaged art to a nonviolent insurgency.

Throughout the book, he seeks to bring visual-art phenomena, ranging from the protest art of Gran Fury to the boosterish “Cows on Parade,” into a dialogue with other kinds of image-makers and experience-crafters, such as Starbucks and IKEA, in hopes of illuminating what they have in common in terms of the call to action they issue to various publics.

Also the artistic director at New York-based public arts organization Creative Time, the prolific Thompson has published four other volumes, including Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the 21st Century and Experimental Geography: Radical Approaches to Landscape, Cartography, and Urbanism. Both were published by Melville House, as is the new book, which is out this week.

In a phone interview with artnet News, Thompson talked about whether hope is the opposite of fear, what we gain from putting art in the broader contexts he argues for, and the differences between writing and curating.

Rather than restricting yourself to visual or even performing arts, you take more of a kitchen-sink approach to culture, pulling in highly disparate phenomena, tying art, for example, to advertising, anthropology as a weapon of war, and activism. Make the argument for the reader: what do we gain by that approach?

For those in the arts, I think the gain, and it’s something I’ve been invested in for a long time, is to frame the arts in broader cultural forms, rather than fetishize the conversation of art in conversation only with art. It’s simply accepting the landscape as it is, since the use of culture is not restricted to art in any sense. In order to have a relevant conversation about what art is doing, it needs to be put in conversation with broader forces.

The growing ability to tug on the way people feel or use images to cajole them into doing something, to use the irrational side of people as a tool, is a very profound shift over the last century, one with profound consequences, and coming to terms with it is complex.

Andy Warhol, Large Campbell’s Soup Can (1964). Courtesy Sotheby’s London.

Speaking of activism, you discuss the visual identity or even branding of movements like Occupy Wall Street and more strictly visual-art forms of resistance such as the historic anti-gentrification “Real Estate Show.” Donald Trump will be inaugurated as president the same week the book comes out, and many in the arts are asking, “What can we do now?” What lessons can those people draw from this book?

The Trump situation is obviously a black hole that sucks all conversation into it. The giant, galvanizing force against Trump obscures the situation we’re in. “How can we stop Trump?” is a reasonable and obvious conversation to have, but it glosses over the idea that the right-wing megalomaniac is the problem and that we are not the problem.

The irrational cultural forces that are epitomized by Trump are not exclusive to Rust Belt Republicans. Those cultural forces are at work across political lines, Democrat and Republican.

You discuss the ways that culture is weaponized to exploit fear. Can culture be weaponized against fear?

First, one should never underestimate fear, but rather have a healthy respect for it. I don’t think our emotional registers are such that there’s an opposite of fear that’s just as effective. Hope is not its opposite. It has no opposite. It’s a dominant emotional form, and it’s effective for triggering—you get an immediate reaction.

How to combat that? That conversation is very complicated, and my suggestion, although it’s not an immediate answer, is that people working together to think through things on a personal, long-term basis is very effective. For example, places like union halls, which don’t exist so much anymore but where people came together to not only talk about class interests but also spend time together, were very effective. Producing space and time to think more complexly about things is a counterbalance to being instrumentalized by emotions.

The radical decentralization of information that is social networking today is unleashing forces in us that are very profound. Who we are as individuals cannot help but change. You see people on the streets looking at their phones, but you can’t see what’s going on inside their heads. That isolation from each other makes us more vulnerable to emotional reaction, so we need to produce social mechanisms whereby we think through things together.

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, 2014. Photography by Jason Wyche, courtesy Creative Time.

In your day job, you select and support various kinds of public art projects, from Kara Walker’s Domino sugar factory installation A Subtlety (2014) to Duke Riley’s LED-lighted pigeon performance, Fly By Night (2016). What’s the relationship between staging these projects as a curator and writing about them in the pages of a book? How do the two kinds of work complement one another?

A book is a very different form, which allows you to make argumentation and to go into facts and history. As for public art projects, in the role of our big commissions, it’s about supporting an artist’s dream. The artist is not only the author but the visionary.

In terms of experiencing artworks, I have profound respect for what art can do, but with that respect comes fear of what art can do. It’s a powerful force. Affecting people on a deep, emotional level and reimagining what the world can be is a very profound responsibility. That is the great glory of putting together public art projects.

That said, I want art to be in conversation with IKEA and with Starbucks, because I have profound respect and fear of what those places can do to us, too. We’re always changing and we’re affected by what we come in contact with. What happens if we buy all our coffee at Starbucks and we buy all our furniture at IKEA? And as much as I love public art, one only experiences so much of that.