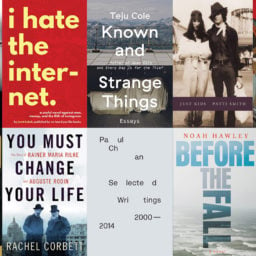

Fall weather encourages diving into a good book. With this in mind, and as a companion to to our roundup earlier this summer, the editors of artnet News have compiled a new list of art-related fiction and non-fiction for the new season.

From the boundary-breaking cultural pursuits in the pages of Unfinished Memories: 30 Years of Exit Art, to Social Medium, Paper Monument’s forthcoming anthology of artists’ writings, here’s what we’re reading.

Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New (1980). Courtesy Amazon.

The Shock of the New, by Robert Hughes (1980)

I have a personal obsession with ideas of newness or modernity throughout history. This book, which was first published in 1980, is a great example of this concept as it pertains to art. The Shock of the New was also a television program that explored the development of modern art since Impressionism, presented by the author and art critic Robert Hughes.

—Amah-Rose Abrams

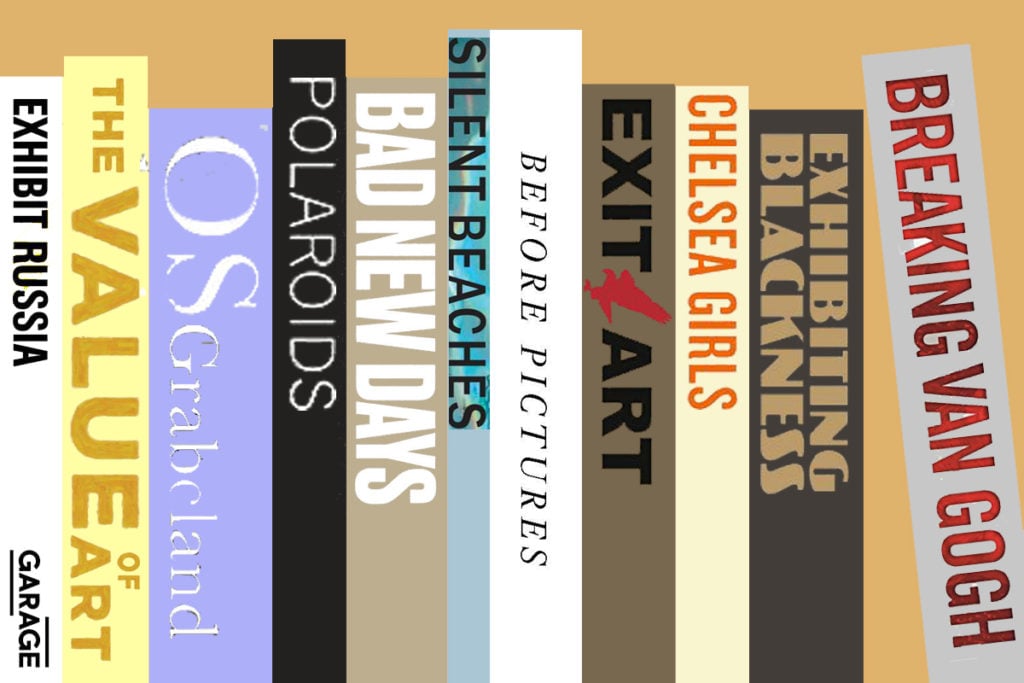

Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade (2016). Courtesy Artbook.

Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade 1986–1996, Garage Museum (2016)

This textbook-like publication is the first in a new series that digs into the archives of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. Exhibit Russia focuses on Russian contemporary art during the Perestroika period and through the collapse of the Soviet Union, specifically in terms of how it connected to the international art scene through exhibitions of Russian artists abroad and Western artists in Russia.

Just because the book is art historical, however, doesn’t mean it’s dry. Edited by Garage curator Kate Fowle and chief editor Ruth Addison, it also features personal testimonies and archival articles from a laundry list of artists, critics, and curators, like Boris Groys, Simon de Pury, and Alanna Heiss. It comes together to read almost like an oral history, and it provides unprecedented insight for English-speakers into this decade of Russian contemporary art history.”

—Alyssa Buffenstein

Related: 15 Gallery Shows Across Europe Everyone Should See This Fall

Breaking Van Gogh: Saint-Rémy, Forgery, and the $95 Million Fake at the Met by James Ottar Grundvig (2016). Courtesy Amazon.

Breaking Van Gogh: Saint-Rémy, Forgery, and the $95 Million Fake at the Met, by James Ottar Grundvig (2016)

Grundvig looks to drop a bomb on New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art with his allegation that its prized Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Cypresses, is a fake. He has a unearthed a compelling story—the painting, allegedly created while the artist was committed after cutting off his own ear, was once owned by Nazi war profiteer Dietrich S. Buhrl, whose children used his art collection to rehab his image.

In his effort to drum up the mystery of the painting’s origins, however, Grundvig, who could have used a more discerning editor to prune overly repetitious passages, reveals the most damning details about the work in a frustratingly piecemeal fashion. At the end of an early chapter, for instance, he criticizes a curator for neglecting to mention that Wheat Field was once owned by Emile Schuffenecker, even though he doesn’t fully explain why historians suspect Schuffenecker was a serial forger until much later in the book.

The Met certainly comes off as worthy of suspicion, with its refusal to release the condition report on the painting, a fact which suggests that is willfully ignoring evidence that the painting isn’t real. But Grundvig’s point-by-point breakdown of all the ways the canvas might be proven a fake still seem to fall a step short of actually providing said proof, despite the author’s concluding assertion that he “proves beyond question” that Wheat Field “is a clear fake, a bad Schuffenecker forgery.”

—Sarah Cascone

How to Be an Artist Without Losing Your Mind, Your Shirt, or Your Creative Compass, by JoAnneh Nagler (2016). Courtesy Amazon.

How to Be an Artist Without Losing Your Mind, Your Shirt, or Your Creative Compass, by JoAnneh Nagler (2016)

Nagler’s refreshingly practical guide to working as artist—without falling victim of the age-old cliché of the starving artis—doesn’t promise Jeff Koons-level stardom. Instead, more realistically, it offers a roadmap for struggling artists who might live a creatively fulfilling life by finding a tolerable day job with humane hours. This also means creating—and strictly adhering to—a weekly schedule with built in time for artistic practice.

To an extent, her advice, especially the section on managing one’s finances, might seem a little self-explanatory, but Nagler doesn’t leave room for excuses. If you’re passionate about your art, she argues, you need to make it a priority, and shape your life around it.

—Sarah Cascone

Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, by Bridget R. Cooks (2011). Courtesy Amazon.

Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, by Bridget R. Cooks (2011)

I’ve been making my way through Cook’s sharp 2011 history of the haphazard ways that US art museums have dealt with African American art and artists, and the debates that have arisen as a result. Even as the National Museum of African American History and Culture opens in Washington DC, this book’s anecdotes provide context for why such a project was needed in the first place, and offers some guidance for controversies about race and representation that are still very much alive.

—Ben Davis

Painting beyond Itself

The Medium in the Post-medium Condition (2016). Courtesy Sternberg Press.

Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in Post-Medium Condition, edited by Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (2016)

Though certainly dense in content, Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in Post-Medium Condition is an important read for those interested in the role painting may—or may not—hold in a contemporary context. Based on a 2013 conference held at Harvard University, the book includes writings by world-renowned art historian Benjamin Buchloh, painters Jutta Koether, Julie Mehretu, and Amy Sillman, and curator David Joselit, among others.

—Caroline Elbaor

Hal Foster, Bad New Days (2015). Courtesy Verso Books.

Bad New Days, by Hal Foster (2015)

Bad New Days reviews the last twenty-five years of art in a critical survey that, by the author’s own admission, falls short in its limited assessment of the Western canon. Even still, the book delivers Foster’s usual mix of academic theory and razor-sharp analysis, examining artists like Cindy Sherman and Isa Genzken (among others) to locate and define the prevailing zeitgeists of contemporary art. Foster may be working in a fixed space, but his power over context makes a convincing case for the continued importance of the critic—Western or otherwise.

—Rain Embuscado

e-team, OS Grabeland (2016). Courtesy Amazon.

OS Grabeland, by eteam (2016)

Franziska Lamprecht and Hajoe Moderegger, a New York-based collaborative art duo who create work under the name eteam, bought a piece of land in 2004 on eBay. It was located in Dewitz, Germany, and had tenants on it who used it mainly for gardening on weekends. Many of them had never left the country. Eteam aimed to improve the “geographic flexibility” of the land by declaring it a cruise ship and having it “cross the Atlantic.” The novel, OS Grabeland, is part document of that project, by the same name, and part artwork. As eteam project their vision onto the land and get others on board for the ride, what ensues is a poetry that investigates the role of art in everyday life. This novel is as hopeful, passionate, and transfixing as the project that inspired it.

—Rozalia Jovanovic

Silent Beaches, Untold Stories: New York City’s Forgotten Waterfront, by Elizabeth Albert (2016). Courtesy Amazon.

Silent Beaches, Untold Stories: New York City’s Forgotten Waterfront, by Elizabeth Albert (2016)

With an engrossing mix of art, photography, and writing, Silent Beaches tells the stories and histories of the lesser-known and forgotten stretches of the New York area’s more than 600 miles of coastline. The book is the brainchild of Elizabeth Albert, a Brooklyn-based visual artist, professor, curator, and writer. Albert writes about the inspiration she took from the Museum of Modern Art’s 2010 exhibition, “Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront,” which was composed of works by five interdisciplinary teams from MoMA PS1’s architect-in-residence program, as well as “Manhatta/Manhattan: A Natural History of New York” at the Museum of the City of New York, which explored New York at the time of Henry Hudson’s 1609 arrival.

Realizing how little she knew about the New York coastal areas in question, Albert began exploring in earnest. “I explored the breached landfill at Dead Horse Bay, the abandoned wrecks at Coney Island Creek, and the ruined beaches across from La Guardia Airport in western College Point. At each location, nature mingled with an amazing array of detritus,” writes Albert. Each of the ten chapters in the book focuses on a particular coastal area across the five boroughs,space, with a mix of images, writing, and history, creating a vivid, if often haunting experience. And each chapter concludes with a piece of short fiction that has been selected by the editors of the online arts journal (and major source of inspiration for the author), Underwater New York. Fun fact (among many I learned): Rockaway, near where I grew up, in Long Beach, was originally home to a small tribe of Canarsie. “Reckowacky,” as it was called, can be translated to “place of our people,” “lonely place,” or “place of waters bright.”

—Eileen Kinsella

30 Years of Exit Art, by Susan Harris (2016). Courtesy of Amazon.com.

30 Years of Exit Art, by Papo Colo and Jeanette Ingberman (2016)

“Her memory is bond into my life and what I can produce is a homage to her,” Papo Colo writes in his introduction to Unfinished Memories: 30 Years of Exit Art, about his partner and co-founder Jeanette Ingberman, who died in 2011.

The duo created an independent space for ambitious and boundary-breaking cultural pursuits in 1982, and the history is contained in the 456-page book by Steidl, which features contributions by a range of artists, from Chitra Ganesh to Tehching Hsieh. Colo explains the guiding force behind Exit Art was “finally, finally—bringing everybody to the table, all colors, languages, genders, attitudes, and desires. No exceptions.”

—Kathleen Massara

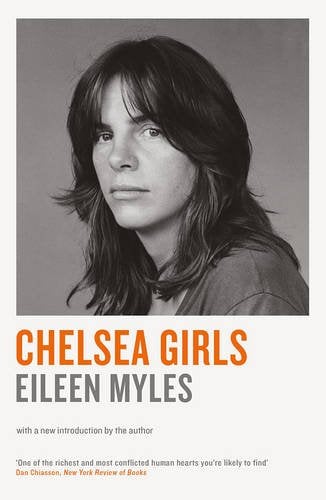

Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles (2015). Courtesy Amazon.

Chelsea Girls, by Eileen Myles (2016)

Until fairly recently, and for over 30 years, Eileen Myles was a cult writer and poet, a relatively obscure figure surviving in the fringes of the literary world of New York. Then came Amazon’s Transparent, endorsements by middle-brow figures like Lena Dunham, and the re-edition last year of her autobiographical novel Chelsea Girls. Then Myles suddenly found herself entering the literary mainstream. I am myself guilty of this much-delayed recognition, as I read, for the very first time—over two decades after it was first published in 1994—a brand new copy of Chelsea Girls, with a hypnotizing portrait of Myles taken by Robert Mapplethorpe in 1980 gracing its cover.

Telling of her comings and goings in 1970s and 80s New York, where she was writing, assisting a poet, and barely making ends meet, Chelsea Girls is an explosion of autobiographical revelations, drugs, sex, and the relentless determination to fight for one’s dreams (in this case, the very noble quest for making a living as a writer). For all her intellectual kudos, reading Myles is refreshingly easy. Her prose reads like being talked to by a friend. It has a colloquial quality, an accessibility, that doesn’t debase its depth and poignancy. It sometimes feels as if Myles was the queer counterpart of the Patti Smith of Just Kids, dreaming similar dreams and living in the very same context, yet boasting vastly contrasting approaches to it all. If, like me, you are late to the party, you are in for a treat.

—Lorena Munoz-Alonso

Michael Findlay, The Value of Art (2014). Courtesy Amazon.

The Value of Art, by Michael Findlay (2014)

Written by the art dealer and longtime director of Acquavella Galleries Michael Findlay, the book offers a concise introduction to art market economics. Findlay explains what determines the value of art, approaching the topic from both the commercial and social perspective whilst also exploring how the various art world stakeholders—from artists and dealers to collectors and institutions—operate within the increasingly complex art world. Insider anecdotes, advice, and other entertaining tidbits make this a great read, offering a thoughtful account of the art market for art world outsiders and insiders alike.

—Henri Neuendorf

Douglas Crimp, Before Pictures (2016). Courtesy University of Chicago Press.

Before Pictures, Douglas Crimp (2016)

Two years ago in Berlin, Douglas Crimp celebrated his 70th birthday with an exhibition at Galerie Buchholz and a two-day event at Kino Arsenal—both titled “Pictures, Before and After”—put together by his friends Diedrich Diederichsen, Juliane Rebentisch, and Marc Siegel, to honor the work of the art critic who coined the term “Pictures Generation.” On stage, Crimp—poised and warm and witty—read out an excerpt from his then-forthcoming memoir to an audience of art historians, gallerists, and thirsty art critics.

The passage he chose was a sharp rumination on how his critical thinking about the work of a certain renowned American painter has transformed in the years since he had penned one of his earliest (scathing) reviews for ArtNews. The self-reflective musings on his change of heart was interwoven with juicy details on the close-knit art scene in 1960’s and 70’s New York, including a later sexual encounter with said artist, who was really into “shrimping.” (Google it).

This delicious memoir is now finally out, succinctly titled Before Pictures, as it focuses on the years leading up to Crimp’s seminal 1977 exhibition at Artists Space, “Pictures.” Crimps’s melding of autobiography, cultural theory, and first-hand accounts of a transformative era in New York’s cultural life—from Chelsea Hotel and Max’s Kansas City to the founding of October magazine—is sure to become a unique introduction to a time that still shapes and impacts cultural life today. Rather than a digression from mainstream record, Crimp’s memoir speaks of the city’s closely linked art and gay communities just before the AIDS epidemic began to ravage the city.

—Hili Perlson

Social Medium: Artists Writing, 2000–2015, edited by Jennifer Liese (2016). Courtesy of Paper Monument.

Social Medium: Artists Writing, 2000–2015, edited by Jennifer Liese (2016)

With the release of Social Medium in October, Dushko Petrovich and Roger White of the journal Paper Monument will have published more books (or pamphlets) than magazine issues, which suggests an ethos to the broader project. Averaging roughly one publication per year, the artists and co-founders tilt toward quality—impeccable editing, genuinely new ideas and approaches—which accounts for their loyal following. (Readers, it turns out, like deliberate writing and thinking.) It also explains why every new Paper Monument publication becomes an event. Social Medium, the century’s first major anthology of writing by artists, promises to be the most important yet.

—Jonathon Sturgeon

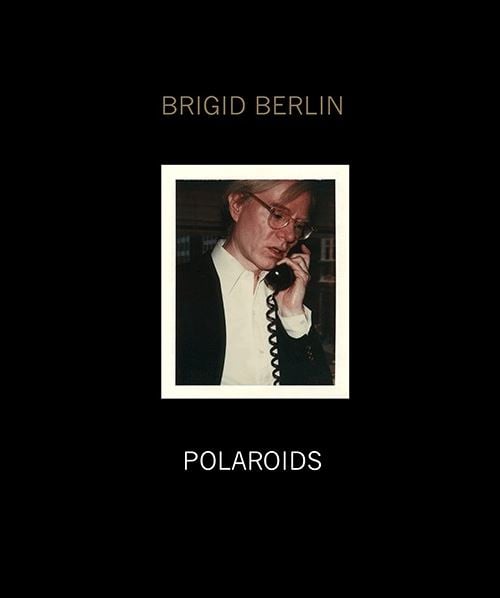

Brigid Berlin, Polaroids (2015). Courtesy Amazon.

Polaroids, by Brigid Berlin (2015)

I came across this book while strolling through the East Village one sunny afternoon—a group of photographers at the Richard Kern exhibition recommended I check it out. A master at taking self-portraits, Berlin’s photographs show a glimpse of the raw and wild talent that she acquired while working as a receptionist for Warhol.

She was a Fifth Avenue debutante and an amphetamine wild child. Formerly known as one of Warhol’s superstars, the new book captures Berlin’s golden days in the Warhol universe. The book features idols in their rarest moments, including Nico and Lou Reed, Roy Lichtenstein, Dennis Hopper, and, of course, Andy Warhol. As I flipped through each page, I felt a sense of nostalgia—the feeling that I missed out on the underground art scene of that era. Now in the age of Snapchat and selfie sticks, I can see why photographers look up to Berlin’s raw power. Although she never saw herself as an artist, she certainly played the role of one.

—Kevin Umaña

Art and Value by Dave Beech (2015). Courtesy Amazon.

Art and Value, by Dave Beech (2015)

Place your thumb over the book’s subtitle at the checkout line, while repeating the following mantra: “This may be the most important book written about art since Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s 1944 Dialectic of Enlightenment.” Rather than broaden the culture industry ditch, Beech argues brilliantly for art’s economic exceptionalism. Despite what Amy Cappellazzo and Jeff Koons say, art is and has always been more than a commodity. Beech makes his inspired argument through a detailed but trenchant economic analysis.

—Christian Viveros-Fauné