Art & Exhibitions

An Eye-Opening Rijksmuseum Show Confronts a History Long Downplayed in the Netherlands: Its Brutal Colonial Rule of Indonesia

The exhibition is a collaboration between Dutch and Indonesian curators.

The exhibition is a collaboration between Dutch and Indonesian curators.

Vivienne Chow

For the Indonesian artist Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, getting Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari (Wounds and Venom I Carry as I’m Running) (2022), a monumental installation inspired by the Bible, on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has been a long, fraught ride.

Commissioned by the museum, the contemporary centerpiece of the newly opened exhibition “Revolusi! Indonesia Independent” is more than the fruits of lengthy Zoom discussions and a challenging, cross-continental research process during the Covid-19 pandemic. The work, which employs historic objects from the Rijksmuseum’s collection, also symbolizes a realignment of Indonesia’s colonial history within the country’s former colonizer, the Netherlands.

“This is like a black box [flight data recorder] that reveals what had happened after a catastrophe, allowing us to reflect on the revolution,” Kusno told Artnet News about his creation. “Where are we standing now? What does history mean to you? Working on this piece has been emotional for me.”

Timoteus Anggawan Kusno, Luka dan Bisa Kubawa Berlari (Wounds and Venom I Carry as I’m Running) (2022). Photo: Vivienne Chow.

One of the powerful European economic concerns that encircled the globe, the Dutch East India Company, arrived in Southeast Asia in the 1600s, and after the company was abolished in 1796, the Dutch government took over governance of the Indonesian archipelago. The nation’s struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949—a chapter of colonial history that had a tremendous impact on many countries, yet that is comparatively under-discussed—is laid out in this major exhibition, which presents some 200 objects on loan from various private and public collections in Australia, Belgium, the U.K., Indonesia, and the Netherlands.

The exhibition, which runs through June 5, focuses on works and records from the period between two key historical events: the declaration of Indonesian independence on August 17, 1945, by the nationalist movement leader and revolutionary Sukarno, and his return to the country on December 28, 1949, the day after the Netherlands finally completed the transfer of sovereignty, following the Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference held in The Hague. A total of 97,421 Indonesians and 5,281 Dutch soldiers died during this period.

“Research and exhibitions in the Netherlands often focus on the Netherlands’ role in this period and its consequences here, but with this exhibition, we aim instead to provide an international perspective,” Taco Dibbits, the Rijksmuseum’s general director, writes in the exhibition catalogue. In particular, he adds, the show’s inclusion of personal histories, those “that were previously denied proper attention,” intends to rectify “a silence that is painful for many to this day.” “Revolusi!” follows the museum’s 2021 exhibition on slavery and the Dutch role in the slave trade and takes a similar tack, by re-contextualizing objects from the permanent collection to reveal stories less often told.

Tony Rafty, Battle of Surabaya (November 14, 1945). Photo: Vivienne Chow.

On one hand, it is an art exhibition, as there’s no lack of artworks on show. Besides paintings by some of the best-known Indonesian artists, such as Affandi, Hendra Gunawan, and Sudjojono, the exhibition also includes protest art and pamphlets confiscated by Dutch military intelligence, as well as a series of sketches of what appears to be a war zone by Tony Rafty, who was assigned by the Australian newspaper The Sun to cover the early months of the Indonesian revolution in 1945.

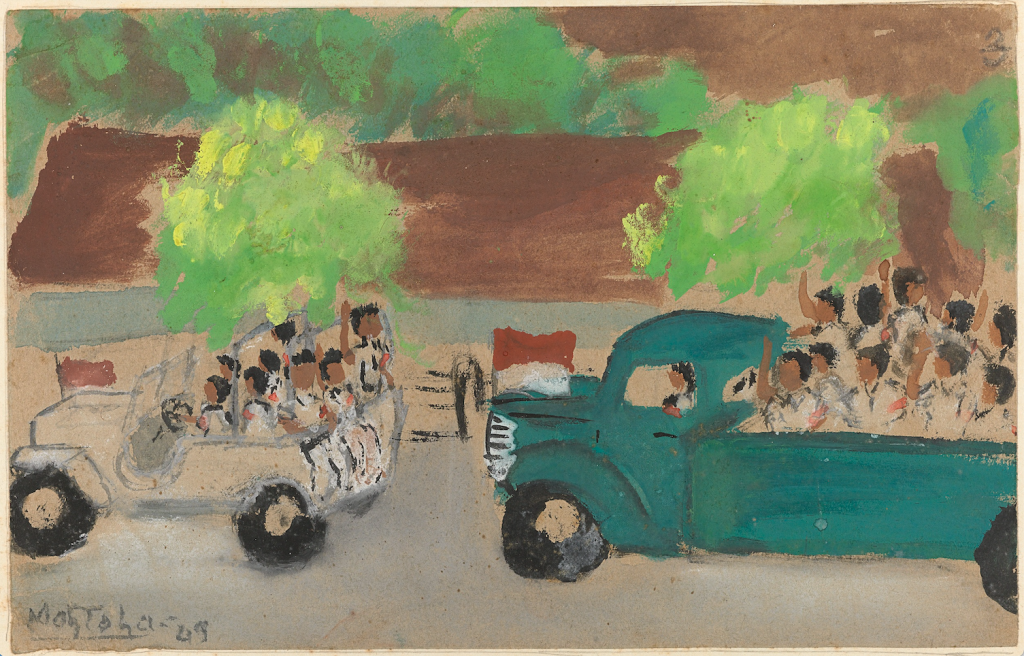

Other important works are miniature watercolors by Mohammad Toha, an 11-year-old boy who was among the five young pupils of realist painter Dullah. Disguised as a cigarette vendor, Toha secretly painted the scenes he witnessed during the Dutch military offensive between 1948 and 1949, which killed hundreds of civilians—including two of his fellow pupils. The Rijksmuseum later acquired Toha’s watercolors.

The exhibition also brings a firm historical backing, presenting an array of archival objects and rare footage to document this pivotal period. It is through these stories, told from multiple perspectives, with personal accounts from 23 eyewitnesses, that “Revolusi!” aims to weave a richer, more complex, and human narrative of Indonesia’s turbulent past.

Mohammad Toha, Republican Troops Returning to Yogyakarta (June 1949). Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

“Revolusi!” is the outcome of a collaborative effort between curators from Indonesia and the Netherlands, who have managed to pull together the show despite challenges presented by the ongoing pandemic. Representing the Rijksmuseum are Harm Stevens, curator of history, and Marion Anker, junior curator of history; their counterparts in Indonesia are Amir Sidharta, director of the Universitas Pelita Harapan Museum and cofounder of the Jakarta-based Sidharta Auctioneer; and Bonnie Triyana, historian and editor-in-chief of Historia.ID.

To Anker and Sidharta, the collaborative curatorial process gave them the opportunity to learn about different versions of history. Both say that making this exhibition has been among the most meaningful projects they have worked on in their career.

“We found new things by accident sometimes. The stories that are told contribute a lot to the general knowledge,” Sidharta told Artnet News.

“We tried to have many different stories. Some may be known to [people in Indonesia] but not to me, because I didn’t learn it in the Dutch school. We hope to present different perspectives in this exhibition. Maybe people can see a part of themselves, and also see things that they do not recognize,” said Anker.

John Florea, Indonesian nationalists ride through the streets with the ‘Boeng, Ajo Boeng’ poster (November 12, 1945). Unknown collection. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The Book of Revelation in the Bible is one source of inspiration for Kusno’s newly created Wounds and Venom I Carry as I’m Running. The installation consists of objects from the Rijksmuseum’s archives, including flags signifying the anti-colonial forces, as well as empty frames that once held the portraits of the Dutch governor-general, laid on the ground as if they were tombstones in a cemetery.

“Colonialism was seen as the doomsday, the end of the world, and the fight against colonialism was a holy call,” Kusno said. “Years later, we are still being haunted by the leftovers of colonialism. Social injustice and the power mechanism [from the colonial times] linger in our contemporary life, and the impact of the colonial policies and governance still resonate today.”

However, Kusno says he appreciated the opportunity to look into a chapter of Indonesia’s colonial history on an institutional level. According to curator Sidharta, a version of this exhibition is expected to travel to Indonesia next year, though details are yet to be announced.

“It’s important to have this dialogue and discussion about this subject, otherwise it would just slip away,” said Kusno.