People

Newfields Director Charles Venable on Why Art Museums as We Know Them Cannot Survive

The controversial museum director explains why audiences today are turned off by Rembrandt and why museums should stop growing—and start shrinking.

The controversial museum director explains why audiences today are turned off by Rembrandt and why museums should stop growing—and start shrinking.

Andrew Goldstein

Amusement parks, as we know, are places of frivolous entertainment, where people can while away the time amid tilt-a-wheels, sugary fluff, and other delights. Museums, on the other hand, are sites of learning and quiet introspection. At least, that’s how it used to be.

In Indianapolis, the iconoclastic museum director Charles Venable seems to be heretically mingling these two cultural models with Newfields, a rechristened “place for nature and the arts” that he has shaped around the Indianapolis Art Museum. Walking through the park surrounding the museum, visitors can encounter exotic foods, meme-video screenings, theatrical productions, and more. Inside, mini-golf and car shows are given equal weight to art exhibitions.

Some people think it’s a cynical, lowest-common-denominator attempt to bring in the crowds. Others think it’s fun. Less contested is Newfields’s success. Membership and admission sales are growing at a fast clip, and this holiday season’s Winterlights show—a “curated” wonderland of one million colored bulbs festooning the trees around the museum—sold 70,000 tickets. Nearly half of those went to visitors who were either new to the museum or had not visited in the past year.

Venable, a veteran museum administrator, believes such attractions are necessary to keep art institutions like his alive in an age of shifting consumer tastes, changing demographics, and fickle millennials. But such measures, he says, aren’t sufficient on their own.

In the second installment of our two-part interview, artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein talks to Venable about why Rembrandt is a hard sell these days, what he learned from shopping malls, and why museums should stop expanding—and instead, consider getting smaller.

Selfie-takers at the Virginia B. Fairbanks Art & Nature Park: 100 Acre. Image courtesy of Newfields.

Many fields are discovering that when you start focusing on metrically determined goals, you start thinking a lot more about how to meet those numbers than about the quality of the product you’re providing. This is something we’re seen in journalism, for instance, with the rise of clickbait and echo-chamber journalism, where you tailor the news to tell a target audience exactly what it wants to hear. It seems something similar is happening at Newfields, where you have had several car shows, like “Revved Up: Cars in Art” and “Dream Cars: Innovative Design, Visionary Ideas.” Clearly, these are engineered to appeal to a broad audience—especially in the home of the Indianapolis 500—but your typical art-loving museumgoer might see this as pandering.

We do get some people who think that way, but the automobile design show that we did with Atlanta [the High Museum of Art], “Dream Cars: Innovative Design, Visionary Ideas,” is a good example. Art people showed up for that exhibition, and they gave it very high marks. They loved it! But a whole bunch of other people who had never been to the museum before also loved it.

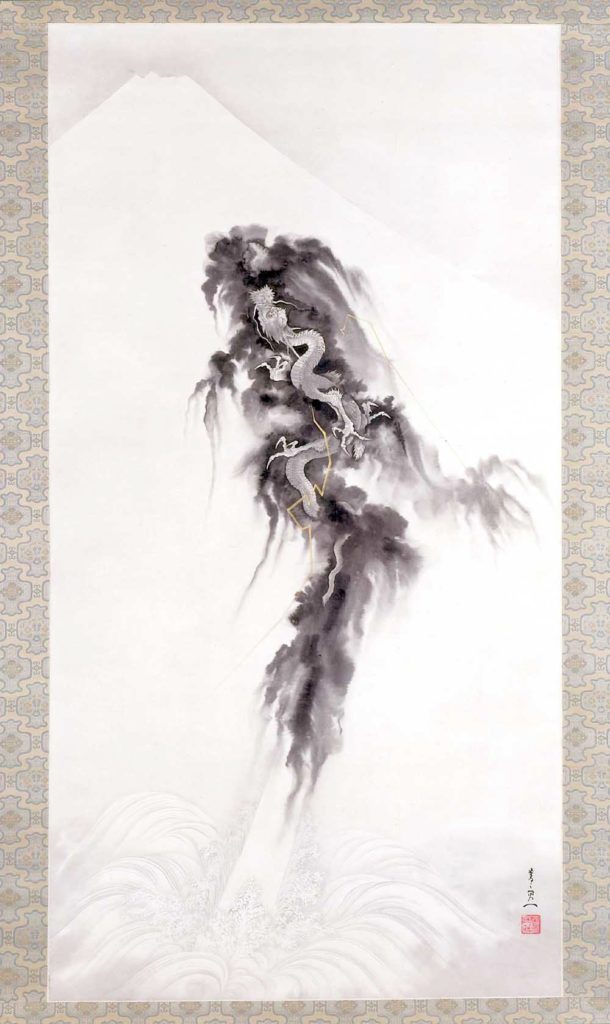

You know, we’re also doing that very traditional, scholarly Japanese painting show, starting in 13th century Japan and going into the 20th century, drawing on one of the great permanent collections in the world. If I did nothing but hang that show and spend all the money that we’re spending on it, that show would have, what, 15,000 visitors in Indianapolis? Which means that my cost per person will be maybe $1,000, even if everyone buys a ticket, because we invest so much more in scholarship for a show like that. I’d be a fool if I didn’t try to figure out how to get 50,000 people to see that show.

The Yoga at Newfields program takes place in the museum’s galleries. Image courtesy of Newfields.

So, the curatorial department has dwindled to six people, the conservation department is down to five, but there were some roles that you recently filled, including a director of hospitality and a director of festivals, performance, and public programming. What does a director of festivals do?

Originally, we had Scott Stulen [who founded the Internet Cat Video Festival at the Walker Art Center with Katie Hill], who created a new job for as curator of audience experiences and performance. But he went off to Tulsa to become director of the Philbrook Museum of Art. So I tweaked his title and added “festivals” in there. Now we have Jeremy Shubrook, and he’s trying to reinvent a program for our three theaters. We have a 550-seat proscenium-arch theater that hasn’t functioned as a regularly programmed performing arts space in a long time. So that’s all another part of Newfields—the performing-arts part of what we do.

It sounds like there are going to be many, many kinds of components at Newfields.

Sure, and they all have to be curated. We’re just trying to align it so if I’m the Japanese curator working on a show about the art of Kabuki, I can go to Jeremy who says, “Well, let’s talk to this company or that company,” so that when someone comes to Newfields their kids can go to the noodle shop, the show, and then they might go for a little Kabuki performance as well.

When you came to the Indianapolis Museum of Art, it was a museum with gardens and all of these other things that people didn’t really think about. Now, you’ve reoriented it so that the museum is one component among all these other elements under the superbrand of Newfields.

Exactly. That’s something we strived to think about: what kind of business are we trying to run? Originally our charter said we were the Indianapolis Museum of Art, period, and somewhere on there was a list of other things. Now, Newfields is the overall campus brand, and under that you have the art museum, the garden and its whole horticulture staff, the Virginia B. Fairbanks Art and Nature Park, all the way to our historic house program.

A screening of “Flashdance” at Newfields. Image courtesy of Newfields.

Obviously, the programming at Newfields has expanded far beyond your traditional museum offerings. Since you joined, the institution has hosted its own cat video film festival as well as a beer garden, mini-golf, and other non-art. How do you view these crowd-pleasing initiatives?

Those were experiments. We’ve been running lots of experiments to see how the needle moves, and so, for instance, Scott Stulen brought the mini-golf with him as a two year-program that he first developed at the Walker. We intentionally decided not to put it in the gardens—we put it on the museum’s sculpture terrace. Maybe 30,000 people came to play mini-golf that summer, and I made sure they bought tickets and went through the galleries. Those people probably would never even know that the galleries existed if hadn’t put the mini-golf in the museum.

This is clearly so far beyond the scope of your typical museum that “museum” is no longer a useful shorthand for what it offers. If you were to quickly describe Newfields to someone who has never heard of it, how would you describe it?

A savvy, fun place that applies curation to everything from Rembrandt to food—and all of the things in between.

So, like Rembrandt to ribs?

Sort of, yeah!

Many museums use peripheral programs to build excitement around their institutions and bring in new visitors, like the Met does with its Museum Workout classes in the mornings. Few art museums, however, make these programs so central to their identity—which makes it seem like you are looking at the museum in a novel way. Are there any other industries, or business models, that you have taken inspiration from in what you’re doing?

Well, I personally like gardening, so when I started here, I discovered this whole world of managing a botanical garden. What I found was that the world of botanical gardens was much more open and sharing. So, when we decided to do Winterlights in our gardens, I was shocked that I could go to the Atlanta Botanical Garden—one of the most successful, highest-attended botanical gardens in the country—and their director and staff would open up all of their books and say, “We lost money here, we earned money here; we have trouble getting African Americans, or we don’t.”

Usually, museums tend to say everything is wonderful: “It’s all just great, everybody came to that show, we’d do it again in a minute.” But if you actually look at the forensics of an exhibition, you see that, hey, that exhibition cost you $2,000 a visitor, so it doesn’t make a difference if it’s free or $18—the economics are so out of whack. Any commercial company would say, “I’m going to just shut down that division.”

Well, I’m not going to shut down the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and neither is my board. So we spent a lot of time looking at the botanical garden business, which is much better at getting a broad base of diverse populations and much better on earned income and donations, too, because very few of them have endowments.

Art museums are exactly the opposite—we’re much better at getting small numbers of big donors to fund us, which over the long term is really dangerous because philanthropy is changing in this country. The kids of the wealthy are not as interested as their grandmothers were in giving the Indianapolis Museum of Art $1 million just because it’s nice. They want to know exactly who is coming here, how diverse the audience is, how their money is going to shape the program, how they will be personally involved.

A young visitor inspecting the splendor at Winterlights. Image courtesy of Newfields.

Were there any models outside the cultural field that also proved useful?

There certainly are. I have friends in the real estate world and the challenges museums are facing are not unlike the struggles that malls are going through. Now, malls are becoming villages where you can spend a whole day, and then on the other hand you’ve got Amazon, with millions of sub-brands.

What we’re trying to figure out is: how big an audience can we link together? For some people, all they care about is art. Others only like gardens. But then a lot more people who like a little bit of art, a little bit of garden, a few noodles, a little beer, and then a stroll through the park with their girlfriend to look at our 35-acre lake in the fall.

In making art less central to the Newfields experience, is there a risk that donors will become reluctant to give their art collections to the museum?

That’s a great question. We’re on the verge of launching a capital campaign, so we did a traditional feasibility study where we talked to all of our top donors, and what we found is that these people—who tend to be older—grew up being primarily engaged through the art museum. They told us, “We love the direction, we love the fact that we go to the museum and there’s a lot of people there and they don’t all look like us, and we love the place being busy. However, we’re personally most interested in the art collection, and so we will participate in your campaign as long as you prove to us that you are taking care of the art museum.” So more than 50 percent of the money we’re trying to raise—and it will be will be $75 million or maybe as much as $100 million—will go to very old-style, art-centric things.

Now, we’ve never had a single endowed curatorship—and that’s one reason Max had to let curators go, because we didn’t have any money in the bank to support them. So, I want to endow all of our curators, including an African art curator. We haven’t had an African art curator in years, and we have several thousand works of African art. I’ll also be announcing a new American curator, and I don’t think we’ve ever had a full-time one. But these curatorships are $3 million apiece to endow. I also want to build an endowment fund for exhibitions and exhibition research, and for our conservation staff.

What I’m not going to do anytime soon—though I wish I could—is have three curators just for contemporary art. As soon as I can hire new curators, I’ll begin rebalancing, so we have more coverage across more of the world, as opposed to building up one or two areas that are in huge debt.

When you are hiring a curator, what are three attributes you look for in an applicant?

They have to be knowledgeable, and they have to want to do scholarly work. That said, they have to have flexibility. I’m not going to hire a curator with years of experience who wants to sit in their office and write books and, on occasion, buy a work of art, but basically stay very quiet. People come first—meaning I want curators who want to engage the public across the whole spectrum, from a person who is terrified of art because they never studied it in school all the way to a very sophisticated collector. I want people who like doing that.

The Beer Garden, located at the Madeline F. Elder Greenhouse at Newfields, is open spring through fall and features a seasonal menu featuring local vendors. Image courtesy of Newfields.

And would these be curators at the IMA or at Newfields?

It depends. I have curators of art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, and that’s what their business cards say. But I have curators of plants too, because we have botanical gardens. I now have gold-pin-level sommeliers, who are kind of like curators, and a curator of culinary art.

Can you talk a little bit more about the “flexibility” you look for in a curator?

The ideal curator is someone who loves getting in a room and talking about ideas with a team of people. We’re no longer in the old world, when I could walk into a director’s office and say, “I want to do the biggest show of silver from 1840–1940”—and never even think, “Is there an audience for this scholarship?” We actually chart how long visitors stay at exhibitions, and once you hit 40 objects, attention plummets and they just walk very quickly through the rest of the show. So, we would say to the curator, “What a great idea, let’s talk about that. Can this show be done in 40 to 50 objects, as opposed to 500?” or, “Should it be a book, and not an exhibition?”

It’s fascinating how metrically driven the decision-making process is.

But it also allows me to do more exhibitions over time—because I didn’t spend all that money shipping those extra few hundred objects, which very few members of the public would pay any attention to.

Considering that you see smaller shows as being more efficient, do you think a smaller museum would be more efficient too? Would you ever consider shrinking the museum’s footprint?

Well, lord knows there are many things that keep me up at night. If it were easier to do, you could say, “Well, let’s just see what happens if we just take the true cream of our collection and hang it in a different way so it has more energy.” But because the way our floor plans work, you can’t just close a part of the building—it would just look like a construction site. We did think about it, but that was a constraint.

It’s funny, because every other museum director talks about expanding their gallery space all the time.

I think we will all live to see the exact opposite: the contraction of museums and other organizations. Because so many museums want their collection to be needlessly big, and you need financial resources to care for collections. Do we need one million objects? Should Indianapolis’s collection be 55,000 objects one day? I don’t know the answer to it, but I think it’s one of the most fascinating questions today.

Would you consider shrinking the museum even if the audience is growing?

I would even if Indianapolis were twice as big! Even if we have four million people and were the size of the Dallas Museum of Art—but we already have more objects than Dallas owns! I grew up going to the Kimbell Art Museum, going to the Frick. They’re not very big, but they have beautiful, high-quality collections. My joke is that nobody ever criticizes them for having 500 works of art, because they’re all great masterpieces. The walls are nothing but star-studded firepower. It’s what you’re actually showing the public that makes your reputation. And we’re all just stockpiling stuff like mad.

Suzuki Kiitsu’s Rising Dragon and Mt. Fuji (1800-1865) will be in “Japanese Masterworks from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” opening fall 2019. Image courtesy of Newfields.

I interviewed Thomas Campbell a little while ago, and there are certain similarities between the challenges you faced. You both came into your directorships in the wake of the global economic collapse, found the museum’s finances in jeopardy, and promptly made cuts to the staff while simultaneously charting ambitious, non-traditional plans to reshape the institution’s future. That’s where the similarities end. Campbell, by all accounts, faced a staff uprising and was pushed out by the board. You, however, have just received a 10-year extension to your contract. What would you attribute your success to?

I think, if you get down to the bottom of it, no director will survive long if they do not have the board that truly believes in the direction. So, when we were creating our new strategic plan—which is two well-written pages these days—a subcommittee of the board was put together with people who wanted to spend a lot of time thinking about the future of art museums, and we spent an entire year reading practically every study that’s been produced in the last 20 years.

Our board eventually got very conversant on art museum attendance. Except in a few bubble markets like New York and Tokyo, art museum attendance has been stagnant or in decline since the early 1980s. At the same time, we’ve all spent billions of dollars building art collections, beautiful galleries, and great institutions.

I may not live to see it—certainly my 28-year-old daughter will—but what happens when nobody visits the Old Master collections anymore? In our museum, we have the first known portrait by Rembrandt, made when he was 23 years old, and I often say it’s one of my favorite paintings in the museum. Recently, I was in a class of very smart college kids and told them that—and none of them knew who Rembrandt was.

Well, why should they know? Schools don’t have a lot of art in their curricula. And museums can’t really fix that—there’s not enough money and time to fix the entire US school system—so it’s going to be a sort of continual drift. What do we do to make sure that Rembrandt gets in front of somebody? Maybe we need to take that picture and put it in a contemporary gallery, or we need to interpret it as work by a 23-year-old, instead of by Rembrandt.

These are pretty radical ideas, but it’s pretty clear museums will need to grapple with them more and more as audience behavior changes.

Or they’ll go out of business.

Or they’ll go out of business. So, in the spirit of helping museums avoid that fate, is there any single discovery, or shareable takeaway, that you’ve come across in your analyses that you think museums need to know to create a sustainable path into the future?

I think there is enough research out there to tell all of us that if we value our products enough, we absolutely need to charge for them. This country has such limited funding for the arts, and we institutions—who know what it all costs—have been crazy enough to say that what we do is not even worth the price of admission. So that’s a fundamental issue. What kind of signal are we sending to the world?

You know, commercial companies don’t give away their products for free. Why isn’t Apple giving away all of its phones? Instead, they raised the price to $1,000 and I bet they can’t make them fast enough. And it’s not just rich people buying phones. I mean, there are wonderful lower-income families that come to Winterlights because we’re distributing free tickets and they all have the phone, because they value it enough to spend a couple hundred bucks on the new model to take pictures of their kids and post them online.

Visitors to 100 Acres: The Virginia B. Fairbanks Art and Nature Park. Image courtesy of Newfields.

There are many people who say that charging admission has a chilling effect on audience diversity. Is that something you take into consideration?

Well, we didn’t have a diverse audience at the museum when we were 100 percent free. You can get a diverse audience there—you just have to offer something that they want to do. I think it would be impossible to take the old art museum and somehow magically say, “Now you’re welcome to come and see it.” It wasn’t developed with any input from that audience whatsoever—for instance, nobody on the staff looked like that, and generally they don’t look like that now.

Now we’re doing an Audubon show in the spring, and I think we can more than double our Hispanic audience with that show, bringing in people who will have the opportunity to look at birds and our nature park as part of the experience. Why wouldn’t we push the envelope in that direction? I also think our galleries are going to have to be different, more welcoming.

It’s funny—looking at this bottle of water I’m drinking now, you could drink this in front of the Rembrandt in the Indianapolis Museum. And that’s a minor revolution, because most museums have all of these rules. No millennial is going to stand for 80 rules about how you can’t carry a beverage, you can’t do this or that, with people who look like cops standing around in the galleries watching you. Nobody is going to come. So, why not allow people to walk around with a bottle of water, or maybe a glass of white wine? After all, all those paintings were created for the houses of people who probably partied in front on them on a daily basis.

I’m guessing you probably allow photography in your galleries then?

We do—but that was a huge thing! There were conferences everywhere on the rights and reproductions issues: should we allow people to take photos with their phones? I was like, why are we arguing about this?

People are already taking the pictures—what are you going to do, tackle them? We were one of the first museums that started writing into all of our exhibition contracts that if you lend us your Van Gogh, let’s say, you will allow members of the public to take pictures of it. That’s common now, but that wasn’t common four years ago. Little things like that just show you how deep the issues are. How do you change this giant ocean liner’s course? I just worry that, by the time we do, nobody is going to be left dancing on the dance floor. It’s a fascinating moment to be alive in the museum business.