Art & Exhibitions

Take a Look at Nicolas Lobo’s Sculpture Series Created In a Swimming Pool

One sculptural element is a giant "ecstasy pill" with a Versace logo.

One sculptural element is a giant "ecstasy pill" with a Versace logo.

Cait Munro

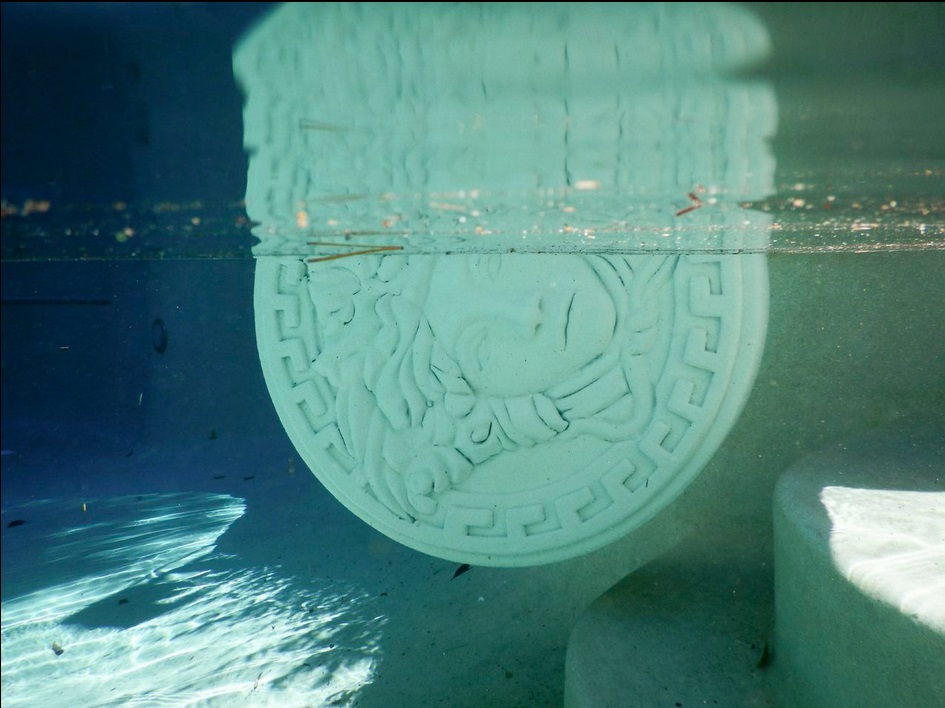

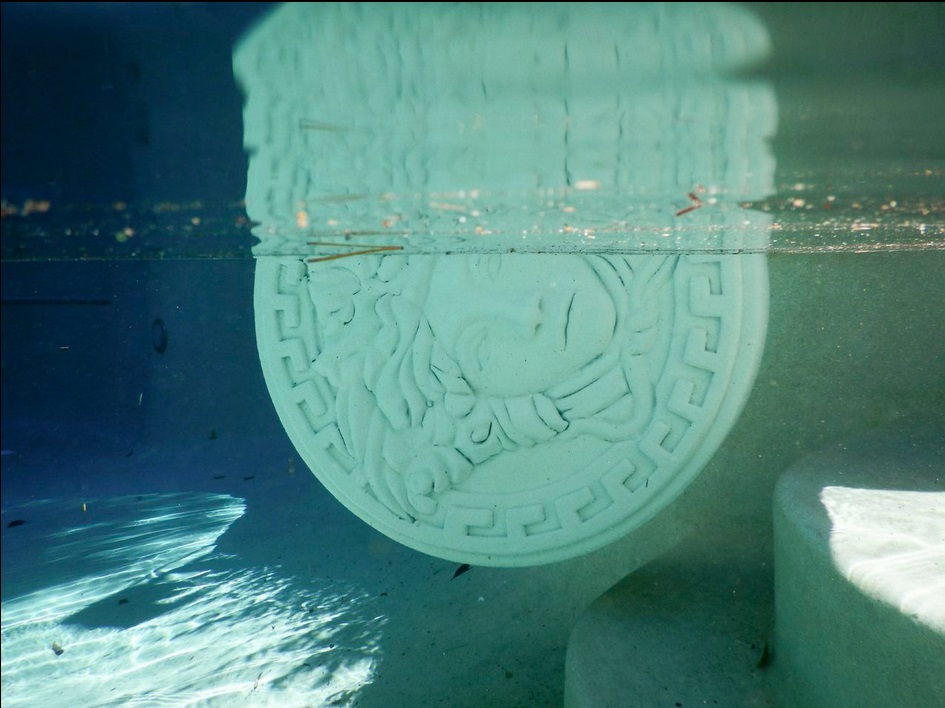

Nicolas Lobo, The Leisure Pit (2015). Detail.

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Gallery Diet, Miami.

In New York, London, and Berlin, artists frequently shell out big bucks for small studio spaces in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods they’ll soon be priced out of. In Miami, artist Nicolas Lobo has found a creative solution to this problem—he’s been working out of a borrowed swimming pool.

For The Leisure Pit, a site-specific installation of mixed-media sculptures, which just opened at the Perez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), Lobo has created almost every work within the still blue-green watery confines of a local swimming pool that he’s temporarily converted into a place of artmaking.

“One of the main themes that came up during this project was the labor/leisure division of time,” Lobo told artnet News via email about why he decided to work in a swimming pool. “It’s this working class thing but I think it’s one of the main themes pushing Miami along as a city right now. There is very little labor here that is not in some way connected to the leisure industry…[it’s] a resort town that means business.”

Personal pools are a symbol of upper class luxury and by turning one into a site for production, Lobo hopes to highlight the oft-overlooked connection between private leisure activities and the demands they make on public infrastructure systems. Simultaneously pulling on threads as seemingly disparate as drug culture and Greek mythology, the project explores the various dichotomies that define modern day Miami—labor and leisure, production and consumption, kitsch and extreme luxury.

Nicolas Lobo.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Lobo, who was born in Los Angeles and earned his BFA from Cooper Union in 2004, is known for process-oriented sculptures and installations made with unusual materials. A recent solo show at Miami’s Gallery Diet called “Bad Soda/Soft Drunk” featured abstract works made using Napalm and a banned Swedish soft drink called Nexcite, which is rumored to boost sexual desire. Lobo was introduced to the elixir when he stumbled upon an abandoned warehouse full of it while checking out possible exhibition spaces in Miami’s Opa-Locka neighborhood.

“Nick’s practice really revolves around him identifying sites of interest within the urban landscape and then importing the kind of materials or processes that are really indigenous to that site,” said curator Rene Morales in a phone call, “and then just drawing from it everything that he can.” Morales has been following Lobo’s career for about nine years and describes him as “one of the most interesting artists in town, and someone who can also really contribute to international conversations.”

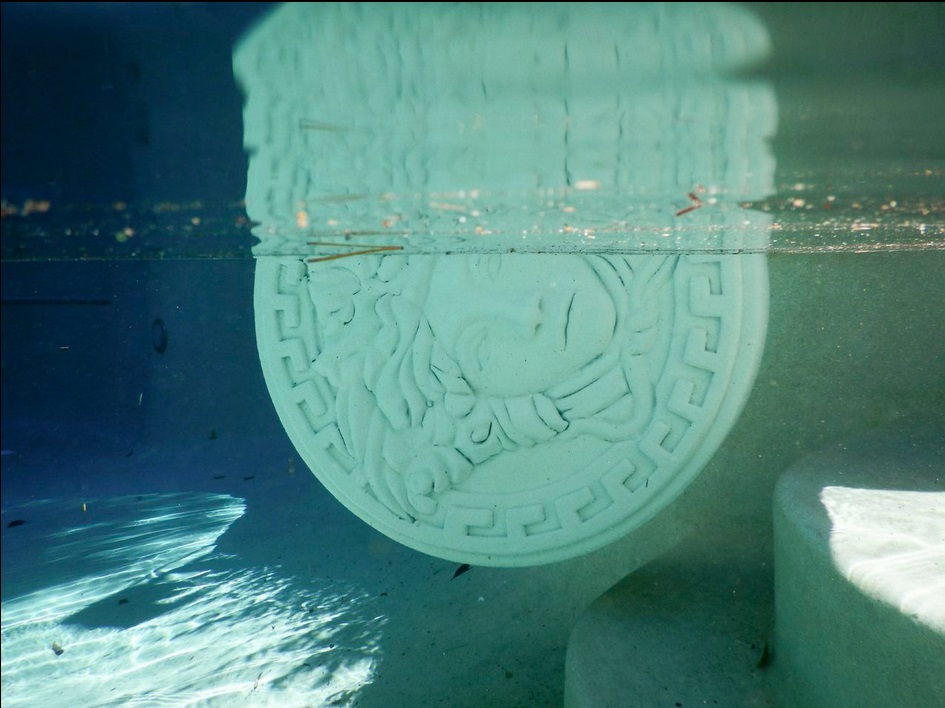

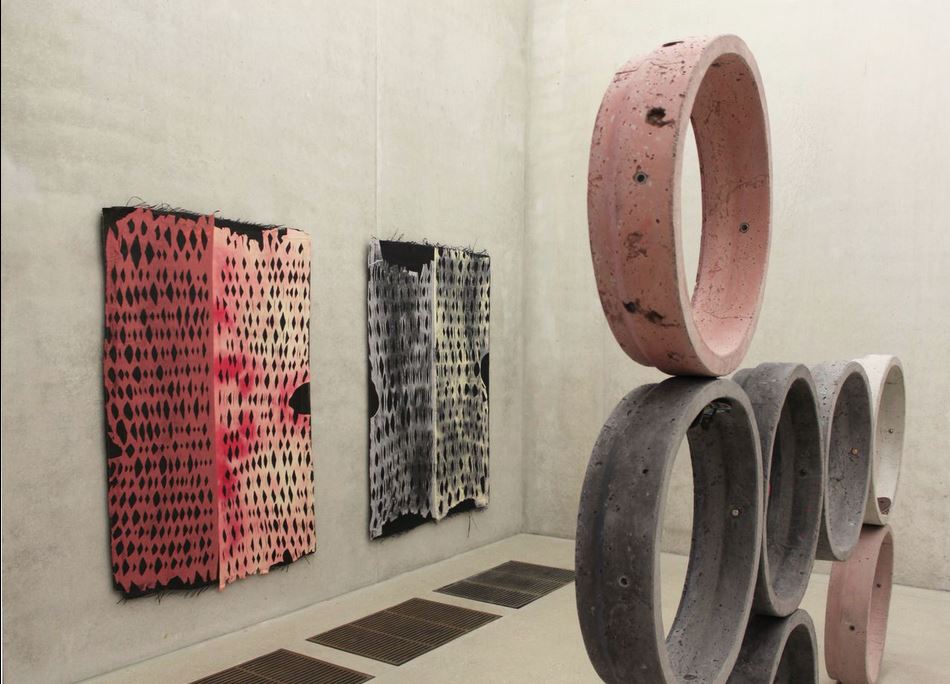

Nicolas Lobo, The Leisure Pit (2015). Installation view.

Photo: Courtesy the artist and PAMM.

To create the array of large sculptures that comprise the installation, Lobo submerged several molds filled with powdered concrete, allowing the weight of the water to solidify them over time. Lobo has described his process as “experimental,” meaning that there are variations between the sculptures, and some were inevitably born out of mistakes.

“One of the more memorable failures involved a pound of aluminum powder, 80 pounds of concrete, and some concentrated pool chemicals,” Lobo recalled. “The idea was to make a metallic storm drain ring with lots of air bubbles. I knew there would be a reaction, which I wanted, but it got a little out of control and it ended as a giant boiling blob of hot metallic goo all over the pool deck.”

Luckily, Lobo was working in a pool loaned to him by a couple of very generous and tolerant friends who he referred to only as “Nina and Dan.” “Their pool is kind of weird because it’s this glass-tiled, Titanic-themed thing that came with the house,” Lobo said. “They are planning to renovate it at some point so any accidental destruction was not going to be that big of a deal.”

The final product is a series of large, ring-shaped modules cast from the storm drains that exist at the bottom of all swimming pools—a reference to the city’s concerns regarding rising ocean levels, which threaten the very foundation—a porous rock called oolite—that the city is built on.

“Miami is a slowly drowning city,” Morales lamented. “It has an expiration date.”

The creation of The Leisure Pit.

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

The other major sculptural elements are the round, pill-like tablets stamped with a Medusa-headed Versace logo, a reference to a legendary local strain of the club drug Ecstasy.

“I really like the idea of throwing a giant pill into a pool to dissolve,” said Lobo. “The whole ecstasy thing is an all-over sensual body experience which I think the pool provides as well, although from the outside-in rather than inside-out as in the case of ecstasy.”

“I thought [the reference] might be slightly too heavy but nobody who comes in cold to see the piece has picked up on the Ecstasy thing yet so I’m feeling like it’s kind of latent actually,” he continued. “What I was interested in really was Medusa, the mutable way in which images of her have traveled through time. The Medusa object is many things at once besides acting as the mold for the storm drain rings. It’s a piece of poolside statuary, it’s the Versace logo which has a very prominent history in Miami, a famous ecstasy pill stamp, and a reference to the Roman interpretation of Greek sculpture, all in one object.”

For a touch of Floridian good measure, plastic flip-flops emblazoned with kitschy palm trees are affixed to several of the sculptures. Hung on the gallery walls, there will be a set of carbon fiber panels made from t-shirts that have been treated with pool chemicals and compressed using a pool pump.

Nicolas Lobo, The Leisure Pit (2015). Installation view.

Photo: Courtesy the artist and PAMM.

Nicolas Lobo, The Leisure Pit will be on display at the Perez Art Museum Miami through December 13, 2015.