Art & Exhibitions

Iconic Photographs Capturing Early 20th-Century Nightlife Go on View in New York

A show at Marlborough gallery features photographers including Weegee, Brassaï, and Helmut Newton.

“Nightlife,” a new exhibition at New York’s Marlborough gallery, brings together the works of six photographers known for chronicling the nocturnal goings-on of European and American cities in the early 20th century, including Berenice Abbot, Brassaï, Bill Brandt, Weegee, Helmut Newton, and Irving Penn.

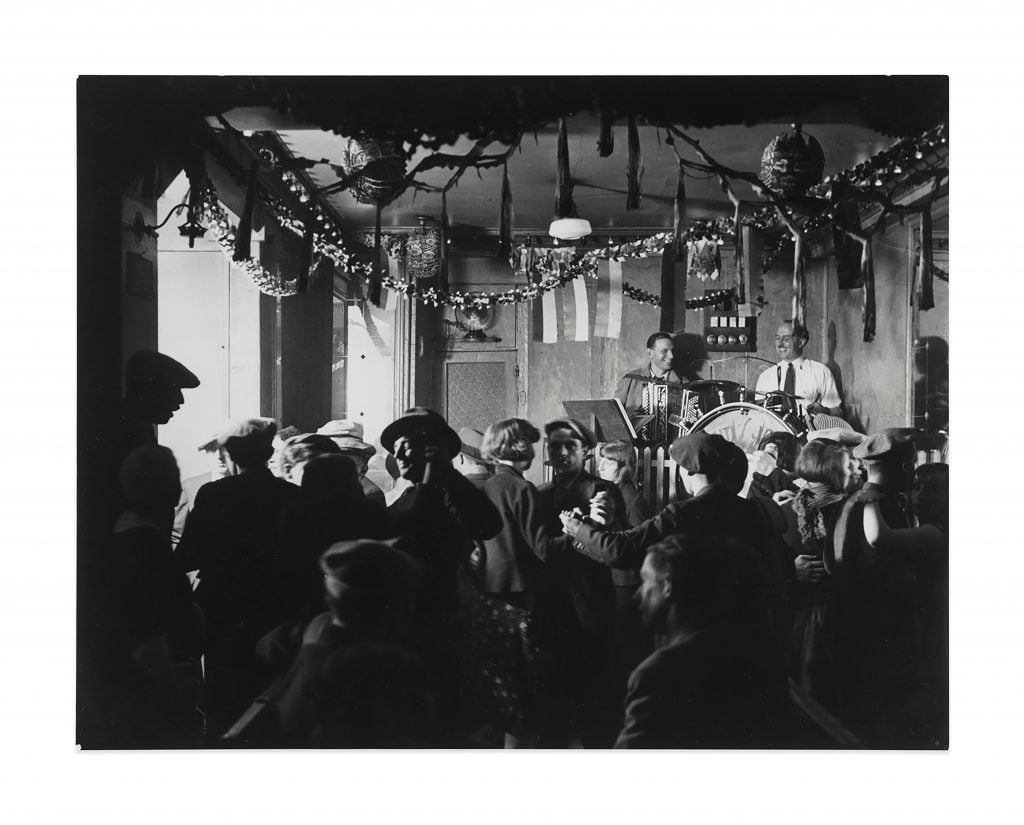

Each of these photographers approached their subject from a different angle. In the 1920s, French-Hungarian photographer Brassaï spent his evenings walking past Parisian bars and brothels, armed with his camera and 24 glass plate negatives. His images variously captured the intimacies, excesses, and joys of night-crawlers, and were celebrated upon the release of his 1933 book, Paris de nuit. Henry Miller dubbed him “the eye of Paris.”

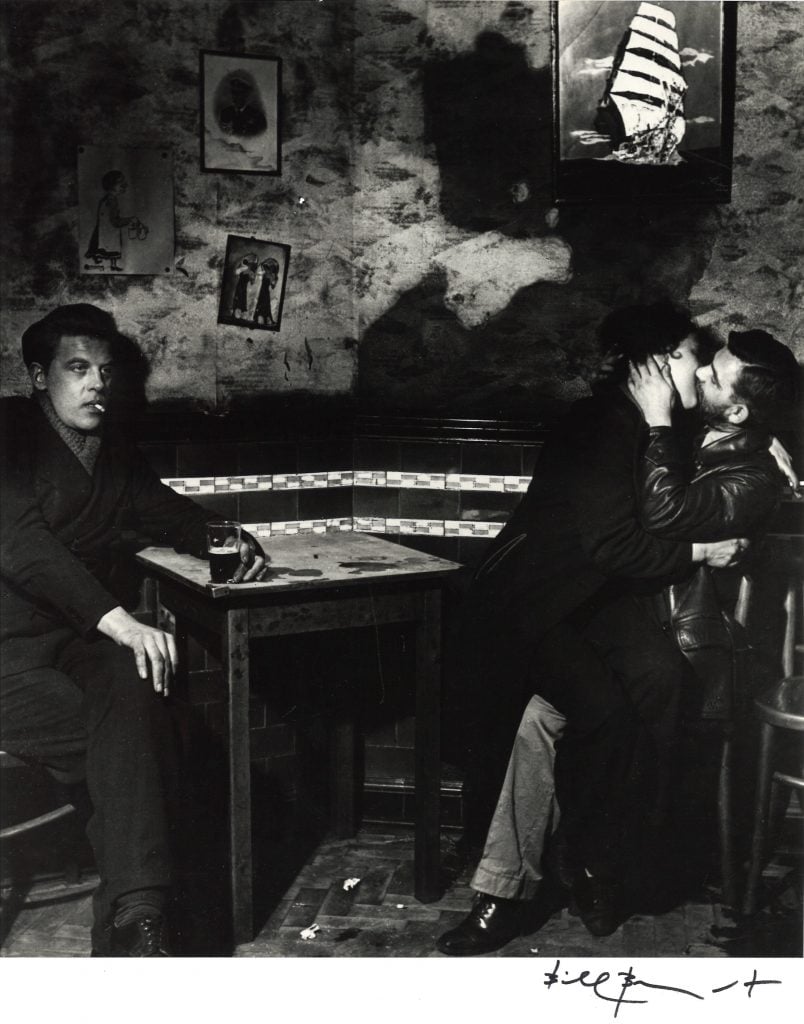

Inspired by Brassaï, Brandt did the same for 1930s London, where he documented the nightly festivities of both the upper and lower classes. His own photography book, A Night in London, published in 1938, offered a glimpse into the prewar night life and labors of British folk across social classes.

Bill Brandt, In the Public Bar at Charlie Brown’s, Limehouse (ca. 1942). © Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Many of the photographs in “Nightlife” were made possible by the invention and commercialization of the flashbulb, which for the first time in history allowed photographers to take pictures in the absence of natural or artificial light. Prior to the flashbulb, visual documentation of nightlife had fallen to draftsmen to record these environments in sketches.

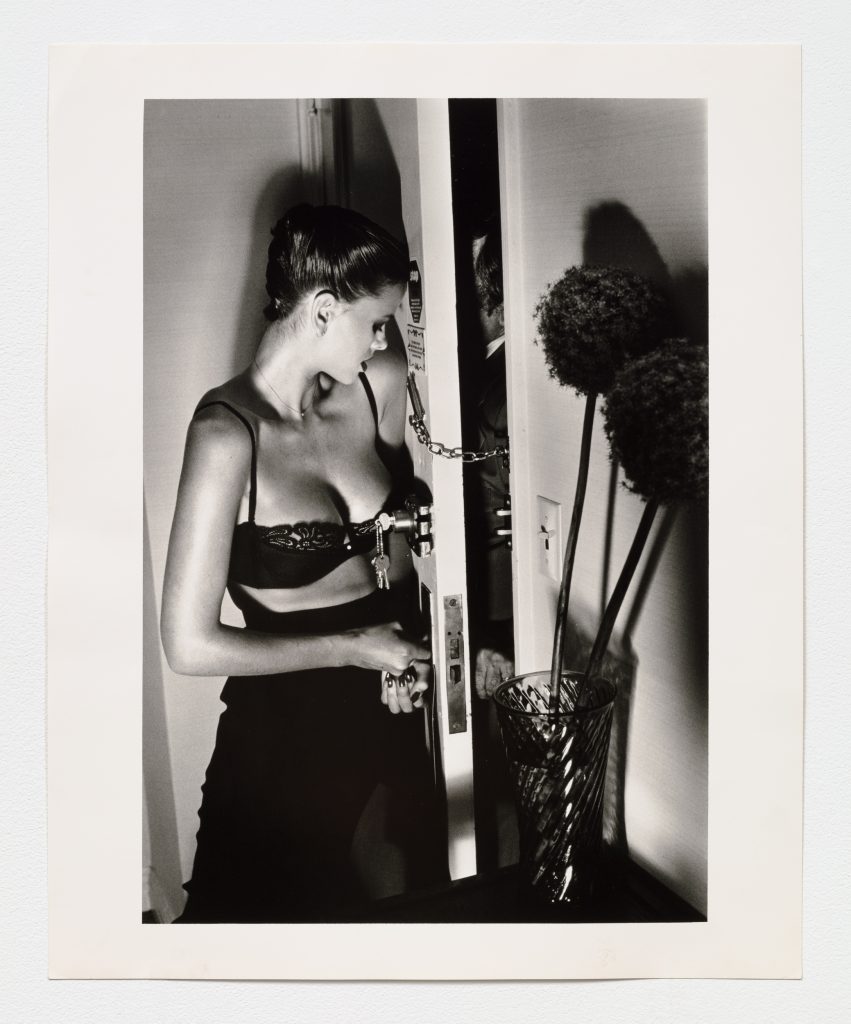

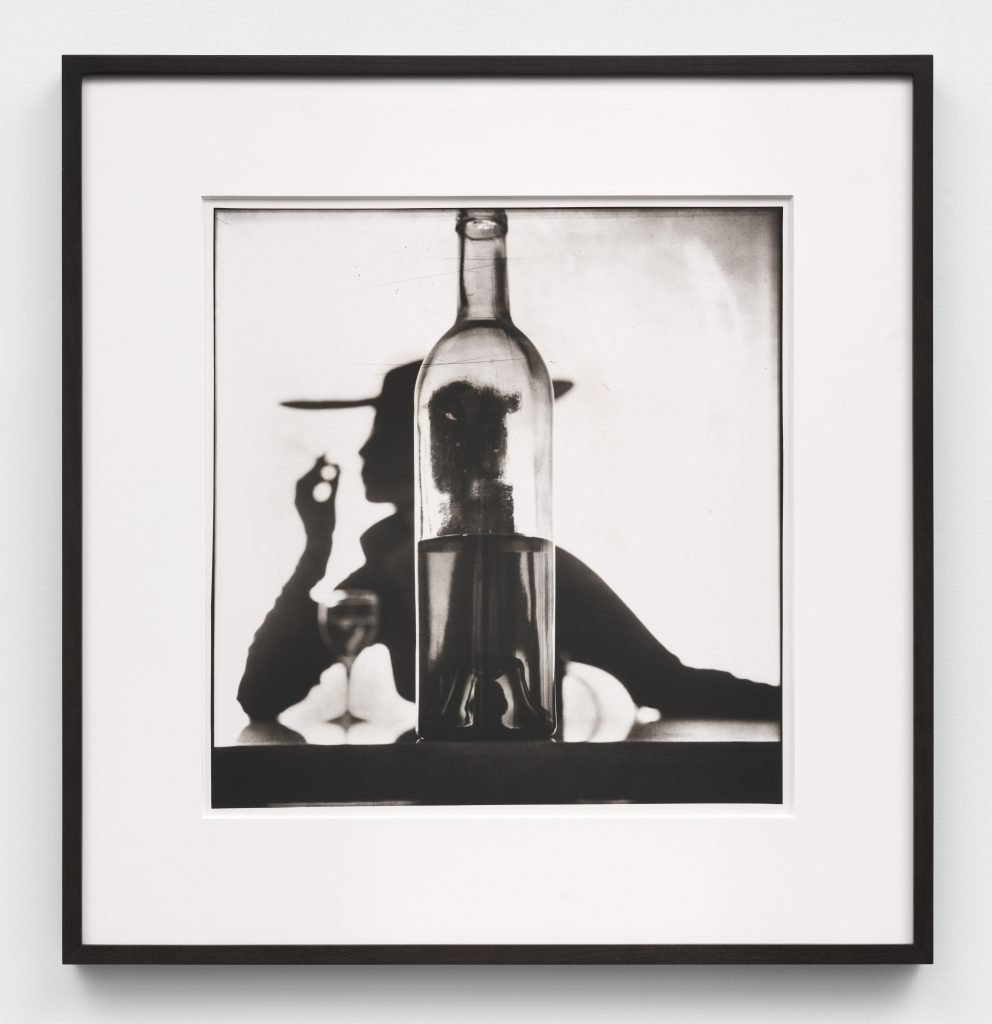

Photographers Penn and Newton, however, worked in far more controlled settings. Both were active in the field of fashion photography and vastly expanded its scope. Penn’s minimalist portraits hinted at nocturnal trends and styles. Meanwhile, German-Australian photographer Newton favored private as opposed to public scenes. His first two photography books, 1976’s White Women and 1978’s Sleepless Nights, are filled with intimate and erotic pictures of fully or partially nude women posing in bedrooms—a reflection of changing gender norms as well as a commentary on the male gaze that turns observers into voyeurs.

Helmut Newton, Security, New York III (1976). © Helmut Newton Foundation. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Then there’s Abbott and Weegee, two New York-based photographers who used the same documentary style to depict the Big Apple from opposite perspectives. Abbott’s images of 1930s New York see her hovering in the sky, presenting skylines, squares, and neighborhoods as they developed over time. The city is in the making and unless this transition is crystalized now in permanent form, it will be forever lost,” she once said. “The camera alone can catch the swift surfaces of the cities today and speaks a language intelligible to all.”

Conversely, Weegee stayed on the ground, listening in on police radio broadcasts so he could capture inner-city mishaps such as crime scenes and brawls in the moment. “What I did,” he said, “anybody else can do.” Though ostensibly a press photographer, Weegee’s dynamic frames appealed to the fine art world: his work was first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943, included the show “Action Photography,” and later compiled in his first photography volume, 1945’s Naked City.

See more images from the show below.

Berenice Abbott, New York at Night (1932). © Berenice Abbott/Getty Images. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Weegee, Lovers at the Palace Theatre (1945). Photo courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery © Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography.

Brassaï, Le bal des Quatres Saisons (1932). © ESTATE BRASSAÏ – RMN-Grand Palais. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Bill Brandt, Hermitage Stairs, Wapping (1930s). © Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Irving Penn, Girl Behind Bottle (Jean Patchett), New York, 1949 (1978). © Helmut Newton Foundation. Photo courtesy of Marlborough New York.

Weegee, Woman at a bar (1940s). Photo courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery © Weegee Archive/International Center of Photography.

“Nightlife” is on view at Marlborough gallery, 545 West 25th Street, New York, March 7 through April 20.