Archaeology & History

This Rare Scientific Artifact Was Long Overlooked in an Italian Museum’s Collection

The astronomical instrument bears markings bearing out 11th-century cultural exchanges.

A remarkable astrolabe showing academic collaboration between Muslims and Jews in 11th-century Spain has been fortuitously uncovered by a Cambridge University history lecturer.

The discovery came last year when historian Federica Gigante was searching the internet for an image of Ludovico Moscato, a 17th-century collector of Islamic artifacts. In a photo of a room at the Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo, the Verona museum that houses Moscato’s collection, Gigante spotted an astrolabe.

When contacted, it turned out the museum had been searching in vain for an expert to examine the astrolabe, an early scientific instrument used to map the stars and reckon time.

Historian Federica Gigante examining the Verona astrolabe. Photo: Federica Candelato.

The scale of the discovery, however, grew significantly when Gigante, previously a curator of Islamic artifacts at Oxford University’s History of Science Museum, travelled to Verona three months later.

While holding the astrolabe in light streaming in from a window, Gigante noticed the brass instrument was marked with small inscriptions in both Arabic and Hebrew. The inscriptions told the story of an instrument that had been wielded by Muslims, Jews, and Christians across Spain, North Africa, and Italy. Gigante’s findings have been published in in the journal Nuncius.

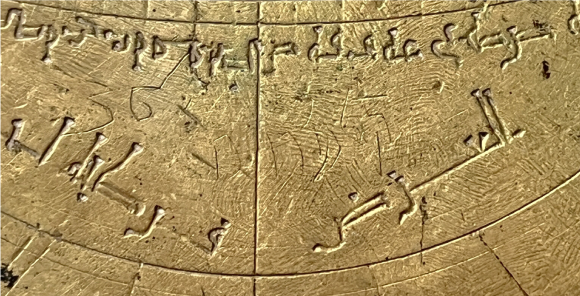

Detail of scratched Western numerals and Hebrew inscription on plate. Photo: Federica Gigante.

The original engraving style indicates the astrolabe was made in 11th-century Andalucía, then Al-Andalus, a Muslim-ruled area of Spain. One plate was marked Toledo on one side and Cordoba on the other. A second added plate has north African latitudes. Together, the markings suggest the astrolabe and its owners travelled the region widely and frequently.

Detail of Hebrew translation on the ecliptic band. Photo: Federica Gigante.

“This isn’t just an incredibly rare object,” Gigante said. “It’s a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews and Christians over hundreds of years.”

The astrolabe is engraved with Muslim prayer lines and names, suggesting it was originally used to properly perform daily prayers. Later markings are signed “for Isaac, the work of Jonah,” indicating the astrolabe had come into Jewish hands, though the text is in Arabic, which connects it the Spain’s Sephardi Jewish community for whom Arabic remained the language of choice.

The astrolabe also has Hebrew inscriptions and translations of Arabic astrological signs, suggesting it later left Spain or North Africa and entered the Jewish diaspora community in Verona, which in the 12th century, had a thriving Jewish community.

The astrolabe likely entered the collection of Veronese nobleman Moscado in the 17th century and passed via marriage to the Miniscalchi family.

Only a handful of such multilingual astrolabes exist with the Verona version among the oldest. “The museum didn’t know what it was,” Gigante said. “It’s now the single most important object in their collection.”