Art & Exhibitions

The First Major Nike Exhibition Offers a Rare Peek Into the Company’s Secret Archives

Watch as Nike goes from selling shoes out of the back of an RV to bestriding the worlds of athletics and fashion.

As company origin stories go, Nike’s is scrappy and wholesome: a fresh-faced MBA graduate teams up with his zany former track coach and together they sell affordable, high-quality running shoes out of a beat-up RV.

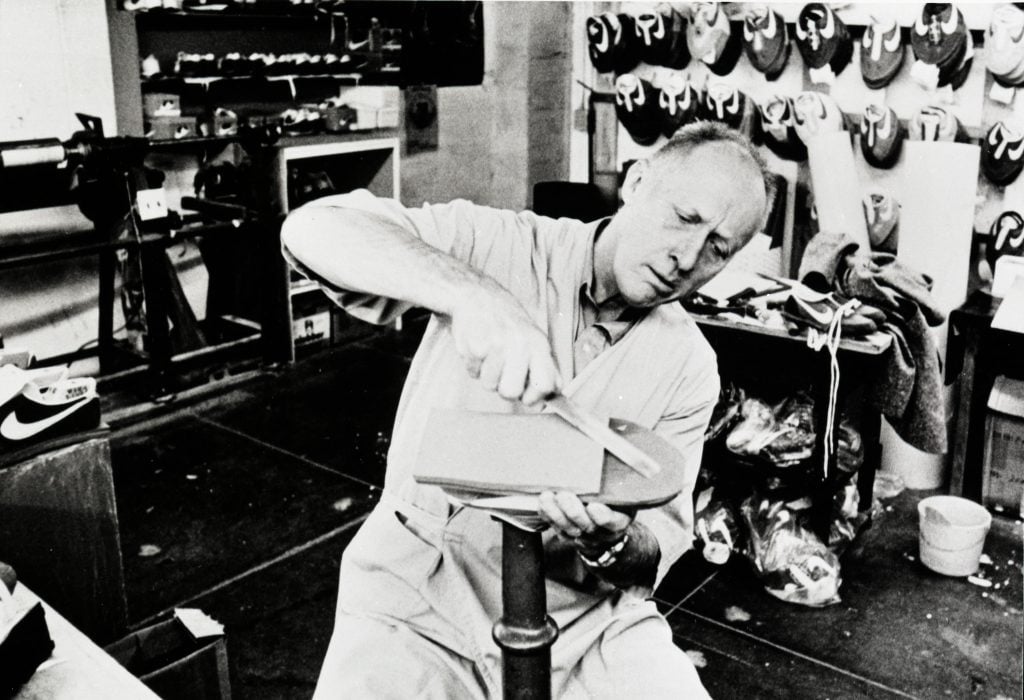

The coach in question, the University of Oregon’s Bill Bowerman, was obsessive in his pursuit of less weight and more speed, forever altering spikes, materials, and heel drops before testing them on his athletes. It was an enthusiasm Bowerman shared with co-founder Steve Knight. Nike’s first success in the early 1970s, the waffle-patterned “Moon Shoe,” evidenced this focus, innovating the grip and durability of running footwear.

Bill Bowerman in his workshop at the Eugene lab in 1980. Photo: Nike/Vitra.

At a time when Nike is among the world’s largest apparel companies, its ubiquitous swoosh as synonymous with fashion and athleisure as with high-performance athletics, it’s easy to forget that at its core it’s a sports research company.

The first museum exhibition about Nike is not simply a sanctioned retelling of the upstart-to-behemoth story, but a reminder of this research-heavy approach. The debut host of “Nike: Form Follows Motion,” kicking off a sustained international tour, is the Vitra Design Museum, in Weil am Rhein, Germany.

Early Mechanical Shox Prototype, 1981. © Nike, Inc.

It’s accompanied by a glossy book of the same name (to be released on December 3), authored by Glenn Adamson, previously the director of New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, now Vitra’s curator at large. The 50-year wait for a Nike exhibition is in part due to secrecy. Until recently, the Department of Nike Archives (as in DNA) has remained closed to the public, a somewhat mythic black box for designers and sneakerheads alike.

A view into the Department of Nike Archives (DNA), Beaverton, Oregon, 2024. Photo: Nike/Vitra.

Adamson has been granted access to DNA (an anonymous building on the company’s sprawling Beaverton, Oregon, campus) and has pored through prototypes, proprietary sketches, one-off creations, and misdirections—some 200,000 artifacts in all.

“The show offers a unique opportunity to focus on design through the lens of a single brand,” Mateo Kries, Vitra’s director, said. “It’s a huge treasure that displays objects that illustrate the process of design development, some of which have never been shown before.”

Various lasts, jigs, silicon pads and fixtures, Advanced Product Creation Center (APCC), Beaverton, Oregon, 2024

© Nike, Inc. Photo: Alastair Philip Wiper.

The exhibition begins with Knight and Bowerman taking on German athletic giants Adidas and Puma by enlisting collegiate and professional runners and relentlessly iterating products. One facet of branding that Nike understood early on was the power of an athlete’s endorsement—those first Waffle shoes were handed out to contestants in the 1972 Olympic trials.

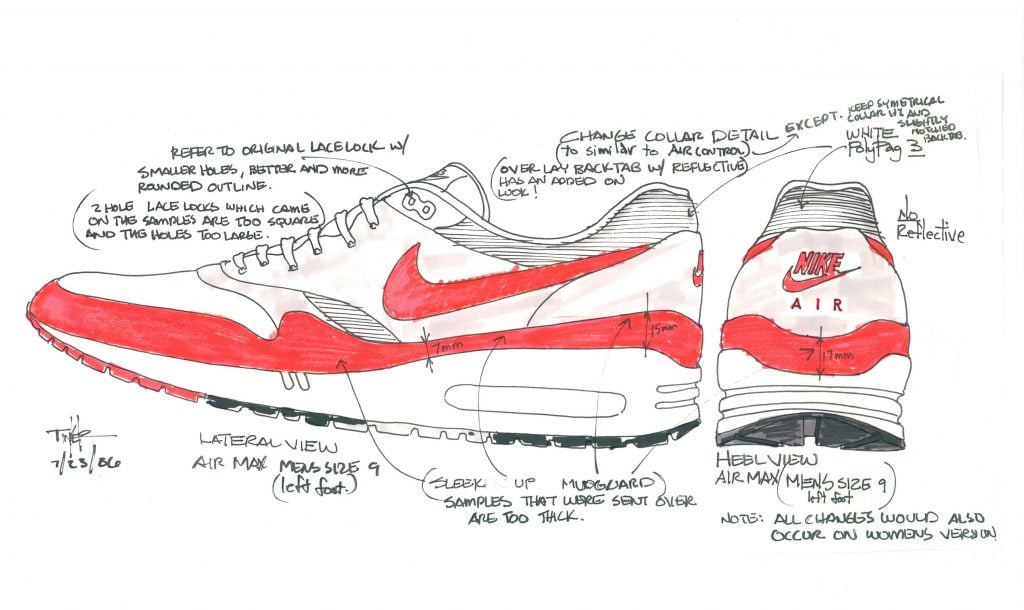

Sketch of Air Max by Tinker Hatfield in 1986. Photo: Nike/Vitra.

In fact, Nike would go on to build its global profile through its partnership with one of the world’s most famous athletes, Michael Jordan, who in his 1984 rookie year with the Chicago Bulls signed a five-year, $2.5 million contract with the company—the largest signed by any National Basketball Association player up until then. Released in 1985, Air Jordans sold $70 million worth of shoes in two months, but the more innovative product came two years later with Air Max, which offered comfort without added weight by concealing a pocket of gas in the midsole.

LeBron James full-size basketball court, Nike Sport Research Lab, Beaverton (Oregon), 2022. © Nike, Inc.

The exhibition transports the visitor to the Nike Sport Research Lab, an 85,000-square-foot gym that tracks athletes through cameras and sensors. It’s the group responsible for Nike Free, which emulates going barefoot; Flyknit, a breathable and seamless shoe that reduces waste by more than 50 percent; and the Vaporfly, the carbon-plated runner released as part of Nike’s quest to allow runners to complete the marathon in less than two hours.

Space Hippie 03 from 2020. Photo: Unruh Jones/Vitra.

The show concludes with a gallery of 50 beguiling examples of Nike’s collaborations with fashion houses and designers—aka collabs. There’s a 3D shoe lab “grown” by Portland, Oregon designer Nikita Troufanov; the so-called Space Hippie, made from recycled bottles and consumer waste; and a soccer cleat-cum-high heel made by Comme des Garçons.

3D grown shoe from the experimental series “The Nature of Motion,” Nikita Troufanov, 2016. © Nike, Inc.

“Over the past 50 years, sport has had a tremendous impact on our perception of the human body,” Adamson said. “The exhibition shows how Nike has both instigated and responded from its initial emphasis on performance and optimization.”

“Nike: Form Follows Motion” will be on view at the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany, September 21, 2024–May 2025.