Art World

Art Bites: That Time Dalí Tricked Yoko Ono Into Paying $10,000 for a Blade of Grass

Ono wanted a hair from the Surrealist's mustache. Dalí sold her something else instead.

Ono wanted a hair from the Surrealist's mustache. Dalí sold her something else instead.

Richard Whiddington

When it comes to Salvador Dalí, the most compelling stories seem at once blatantly apocryphal and perfectly plausible—a definition, of sorts, for Surrealism itself. So it goes with Dalí’s correspondence with Yoko Ono.

The two first met while Ono was on her European honeymoon with John Lennon in 1969. As newspaper reporters shadowed the world’s most famous couple (producing the iconic “bed-in for peace” photographs), the newlyweds traveled from Amsterdam to Paris to lunch with Dalí at the Hotel Meurice.

They had been introduced by the photographer Robert Whitaker, who toured with the Beatles in the mid-60s and had turned a teenage obsession with art’s enfant terrible into a fruitful working relationship (as detailed in his 2007 book, In the Company of Dali).

What the trio discussed is entirely unknown, but it seems Lennon made a strong impression, given Whitaker noted that Dalí later kept a photograph of the Beatle hanging from a coat hanger on his wall.

#OnThisDay, 24th March 1969, John & Yoko met with Salvador Dali for lunch during their Honeymoon in Paris.

Photo by Henry Pessar pic.twitter.com/dJrCkFP3Kw

— John Lennon (@johnlennon) March 24, 2017

Dali and Ono’s relationship endured after Lennon’s death in 1980, though it took a rather bizarre turn. According to Amanda Lear, the iconic French singer and actress who became Dali’s muse after meeting him in 1965, Ono asked for a hair from his trademark mustache.

Ono was willing to pay for the privilege, which enticed the man. Still, Dali hesitated. He worried Ono was a witch and thought that she might use it for occult purposes.

“He didn’t want to send her a personal item, much less one of his hairs,” Lear said in a 2012 interview with French magazine VSD. “So he sent me to the garden to find a dry blade of grass, and sent it off in a pretty box.”

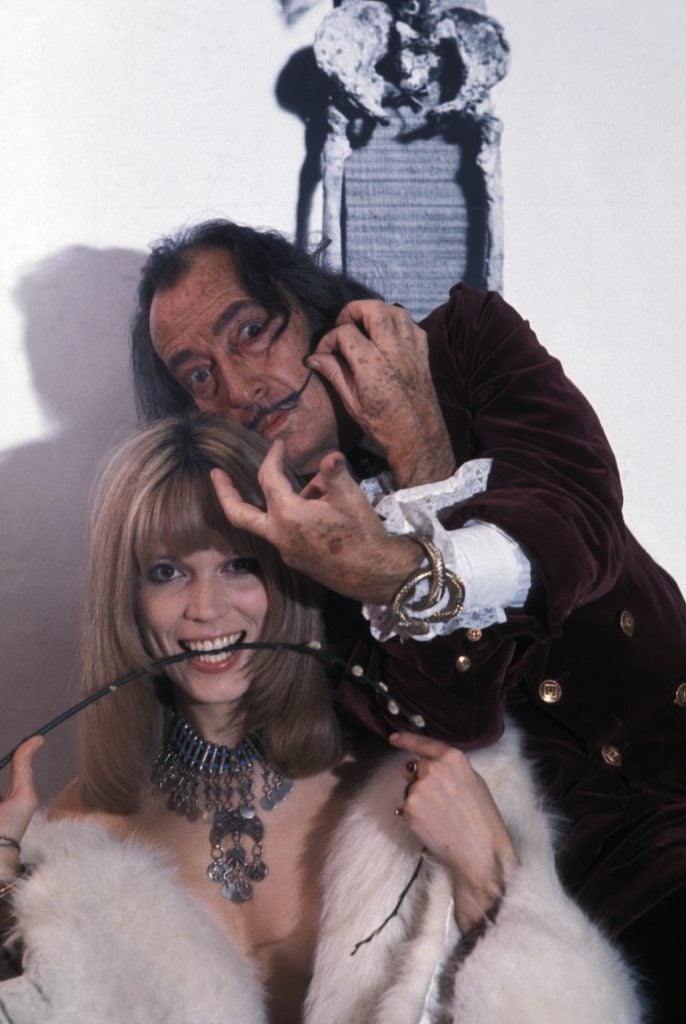

Amanda Lear and Salvador Dalí in the 1970s. Photo: Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

The cost? $10,000. “All his life, he liked to rip people off,” Lear said. “Dalí could not resist when someone waved a big check under his nose.”

While the story as a whole cannot be verified, Lear’s final point is undeniable: Dalí loved money. It explains the gusto with which he pursued advertisement opportunities for brands including, but not limited to, Iberia, Nissan, Wrigley’s, Chupa Chups, Alka Seltzer, and Johnson Paint.

So, too, why Dalí increasingly turned to printmaking in the latter part of his career. He realized he could sketch an idea onto a plate and authorize others to create hundreds of original prints—he even pre-signed blank sheets of paper to streamline the process for his assistants.

True or not, the story is not incongruous with Dalí’s legacy. “Liking money like I like it is nothing less than mysticism,” he once said. “Money is glory.” And what greater glory than ripping off one of the most famous women on the planet.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.