Art & Exhibitions

What If an Artist Were Your History Teacher? A New Photography Exhibition at the Guggenheim Questions How We Depict the Past

"Off the Record" is curator Ashley James's first show at the museum.

"Off the Record" is curator Ashley James's first show at the museum.

Taylor Dafoe

“Fake news” will be a tempting aperture through which to approach “Off the Record,” a new group show at the Guggenheim that looks at the ways in which artists consider, critique, or otherwise manipulate “official” documents of history and state power.

It wouldn’t necessarily be wrong to take that tack. But it’s not what was on curator Ashley James’s mind as she organized the show—her first since becoming the museum’s first full-time Black curator in 2019.

“I’m less interested in speaking to the specificities of our contemporary historical moment than in thinking about a certain position in relationship to history as such,” she tells Artnet News over the phone. She pauses as construction noises from the show’s installation clang behind her.

“It’s about a point of view,” she continues as the din dies down. “It’s about a kind of posture toward history and documentation that is something that’s applicable to the past, to the present, and to the future. It’s more about a methodology.”

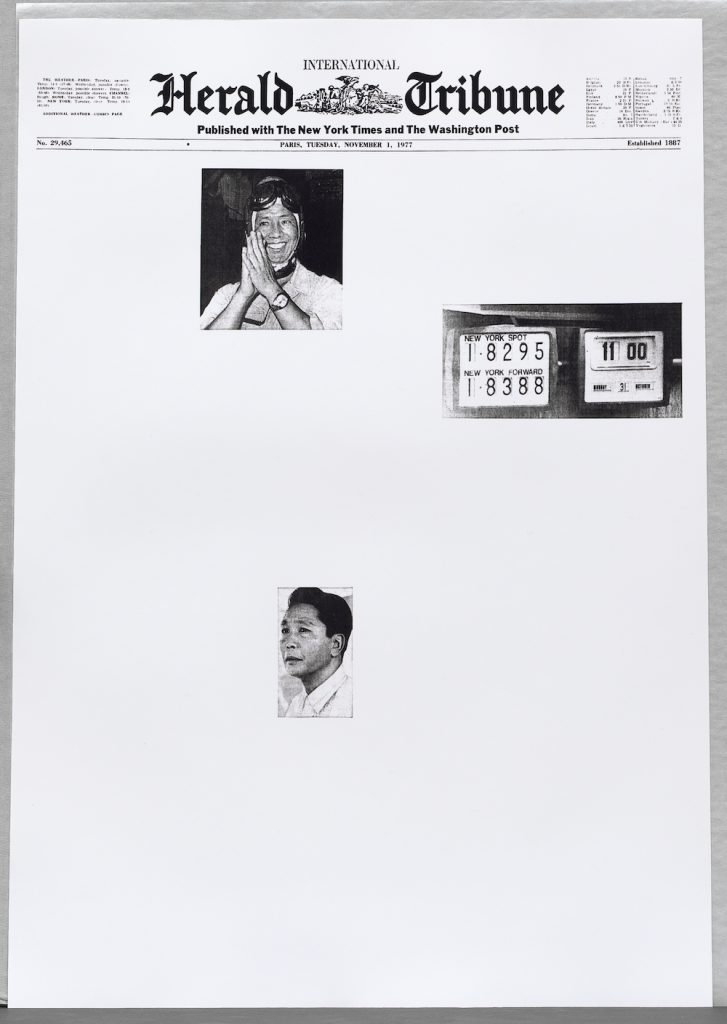

Sara Cwynar, Encyclopedia Grid (Bananas) (2014). Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Heavy on photoconceptualism, “Off the Record” comprises some 25 works—all but one of which were pulled from the museum’s own collection—from artists including Sadie Barnette, Sarah Charlesworth, Hank Willis Thomas, and Adrian Piper. It’s a group that represents a wide swath of generations, interests, and artistic practices. What unites them here, explains James, is a shared “skepticism of received history.”

But how that sense of skepticism manifests in the work varies with each artist. For Sara Cwynar, represented in the exhibition by three pieces from her 2014 Encyclopedia Grid series, it’s an intellectual exercise. Taking a cue from the John Berger classic Ways of Seeing, the artist has culled various pictures of the same subject (bananas, Brigitte Bardot, the Acropolis) from multiple encyclopedias and rephotographed them—a process that shows us, without judgment, the representational quirks and biases of the supposedly objective resources.

Sadie Barnette, My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation (2017). Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Lisa Oppenheim, meanwhile, sees creative potential in the document’s deficiency. For a 2007 photo series, the artist reimagined details redacted from a group of Walker Evans’s Great Depression-era negatives, which were hole-punched to prevent publication. Oppenheim’s own small circular photographs, paired next to Evans’s originals, read as a kind of revisionist history—albeit one that is just as flawed as its source material.

Other examples are more charged, such as prints from Carrie Mae Weems’s iconic 1995-96 series “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” in which the artist appropriates ethnographic photos of enslaved people to show how photography was used to reinforce racial inequality. Each is paired with a pointed phrase: “DESCENDING THE THRONE YOU BECAME FOOT SOLDIER & COOK,” reads one.

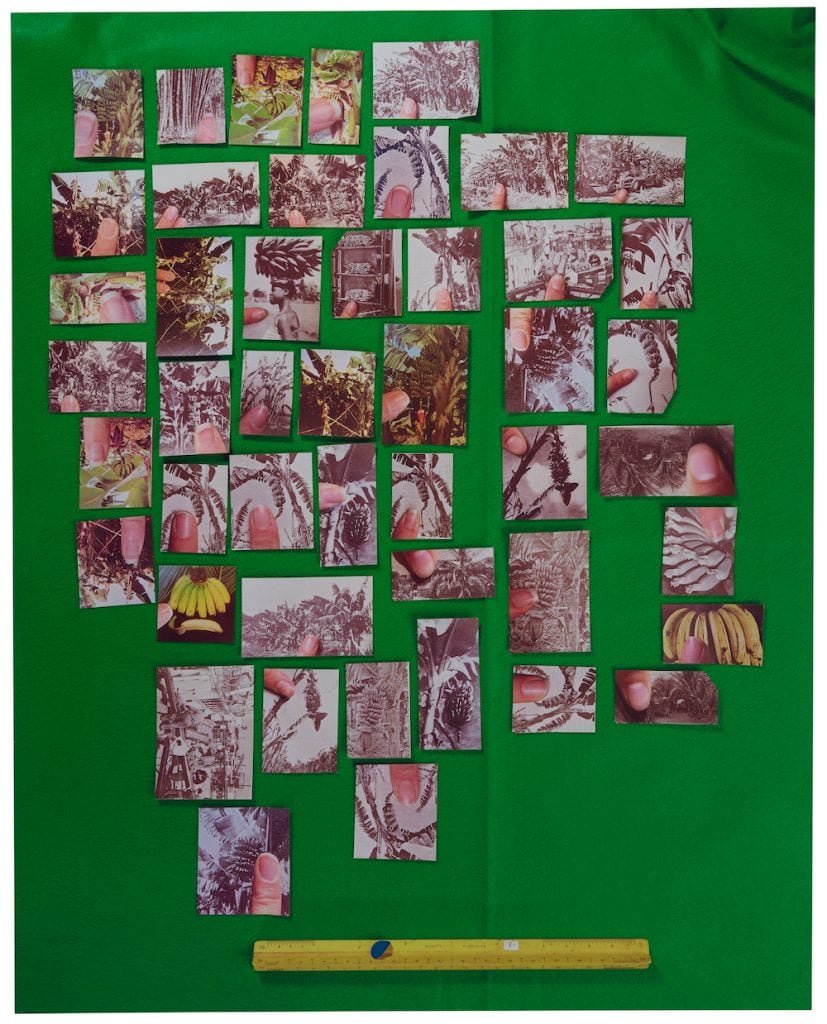

Hank Willis Thomas, Something To Believe In (1984/2007). © Hank Willis Thomas

Photography. Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Like these examples, almost all of the artists in the exhibition draw on material from generations past. But that’s not to say that the show doesn’t have something to say about the contemporary moment, James points out—even if its message has little to do with the Trump era specifically.

Best exemplifying this is the one work in the show that doesn’t belong to the museum’s collection: a 2020 wall-hung assemblage by Tomashi Jackson, in which an archival print of President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act is overlaid with paint and campaign materials for a 2018 gubernatorial race.

It’s a piece that literally fuses the past with the present, the “official” with the unofficial. And it alludes to another theme that ties together the various pieces in the show: “power,” says the curator, ”whether that power is because of the institution itself or power in a narrative that has been received in a certain way over time.”