Archaeology & History

Archaeologists Unearth the Oldest Aboriginal Pottery in Australia

The find refutes long-held beliefs that the Aboriginals did not make pottery.

A new study in Quaternary Science Reviews refutes long-held beliefs that Aboriginal Australians didn’t make pottery. Researchers with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage partnered with the Dingaal and Ngurrumungu Aboriginal communities for the first time to dig on Jiigurru (Lizard Island).

Though their site measured only three by three feet, the 82 pottery shards unearthed over two years have wide implications. These pieces, hailing from between 2,950 and 1,815 years ago, are now the oldest securely dated specimens found in Australia.

According to the study, “The apparent absence of pottery in Australia, as noted by early and more recent European observers… both reflected and was used to support, racist social evolutionary hierarchies characterizing Aboriginal societies as lacking cultural complexity.” Still, researchers have puzzled over this absent material, considering the preponderance of Aboriginal exchange networks and the proximity of pottery-producing cultures like the Lapita maritime people, who settled Oceania from the Solomon Islands to Tonga.

Excavation in progress. Photo: Sean Ulm

In a separate article published the same day, lead researchers Sean Ulm and Ian J. McNiven joined Walmbaar Aboriginal Corporation director Kenneth McLean in translating their latest findings. New Zealand-based archaeologist Matthew Felgate, they recounted, made the first discovery of pottery on Jiigurru in 2006, when he found a single shard while walking in the Blue Lagoon. The find gave no further clues on its own, so Ulms led a team to excavate more pottery pieces between 2009 and 2013.

None of the shards could be dated, but the last spot turned out to be 4,000 years old, making it the oldest human site on the island. Until 2017, that is, when Ulms, McIven, and company returned to excavate another midden—an ancient campsite disposal hole—and struck the 82 shards in question, a mere 1.5 feet beneath the surface. Five feet deeper, they found shells discarded so soon after eating that the insides still had color. These items are 6,500 years old, meaning they were thrown in the midden 3,500 years after rising seas made Jiigurru an island, rendering this campsite the oldest example of offshore island use on the northern Great Barrier Reef. In the study, Dingaal Elder Phillip Baru says Jiigurru was a seasonal grounds for ceremony and scavenging.

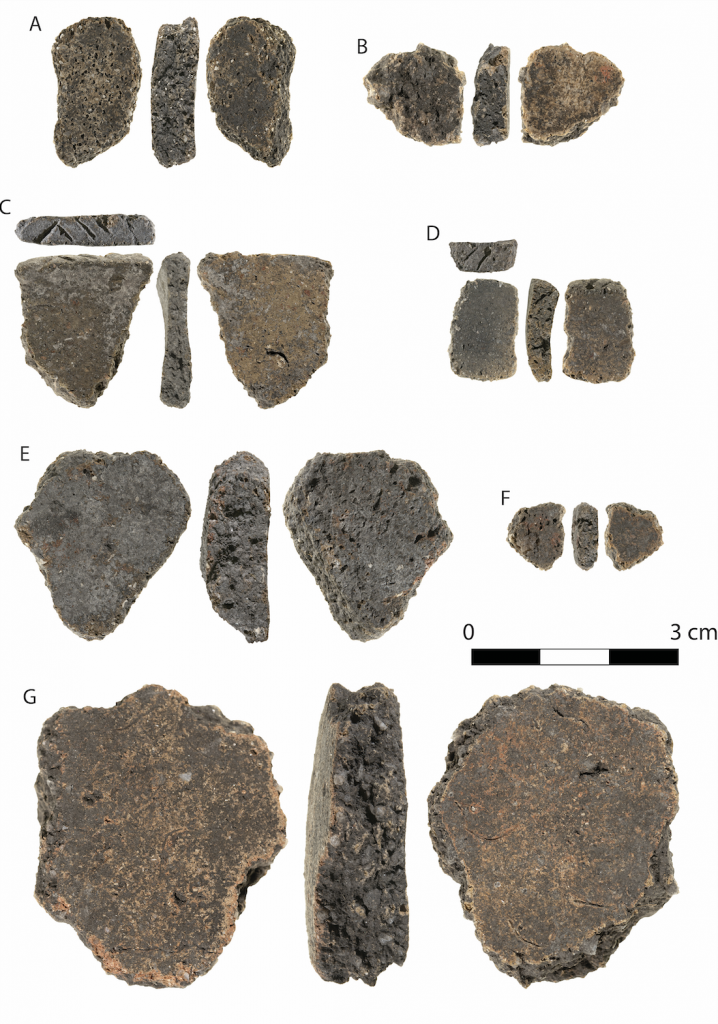

Some of the pottery pieces excavated at Jiigurru. Photo: Steve Morton

The discoveries are proof that these communities were also far more interconnected than once believed. The pottery shards are still too small to know what they were used for. There is a rim, four necks, as well as rim and neck sections. The rims feature decorations of diagonal lines. They are also notably thin. McLean said he believes they are pieces of the clay pots his ancestors used to transport water and shellfish on canoe trips to Jiigurru.

By comparing the shards’ temper to sands from surrounding beaches, the team surmised that they were made locally. They were not shipped in through the trade networks researchers are only beginning to understand, nor deposited by the Lapita, as their calling cards such as the remnants of pigs and bananas were not present. Some experts are skeptical, but agree the science is all there. “I’m certain that our understanding of the Australian past will be rewritten again and again over the next decade through research partnerships bringing together Traditional Owner communities and researchers,” Ulm told Artnet News over email.