Studio Visit

Omar Mismar Mines Ancient Strife for His Stunning Contemporary Mosaics

The artist worked with a master mosaicist displaced by the Syrian War.

The artist worked with a master mosaicist displaced by the Syrian War.

Adam Schrader

Lebanese artist Omar Mismar made a splash at the Venice Biennale with a series of political mosaics inspired by ancient works, some of which comment on the regime of Syria’s strongman President Bashar al-Assad.

The works received praise from Artnet News critic Ben Davis, who wrote that Mismar’s flair “stands out in a show of nearly unwavering sincerity.”

Mismar, a multi-media conceptual artist, was born in the Bekaa Valley of Lebanon in 1986. He moved to Beirut for undergraduate studies in graphic design at the American University of Beirut, where he graduated in 2008.

He worked as a graphic designer in Lebanon before moving to the United States as a Fulbright scholar to earn two master’s degrees—an MFA in art as a social practice and a degree in visual and critical studies—both from the California College of the Arts, where he later worked as a part-time professor.

His experiences are vast. Mismar participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program; he had exhibitions in Paris, New York, Latvia, Brazil, Germany, and the Netherlands; he received several awards and grants for teaching, including as a visiting professor at the Pratt Institute and fellow at the Vera List Center for Arts and Politics; and he has served as an editor for the Rusted Radishes: Beirut Literary and Art Journal.

The artist sat down with me for a video interview from Beirut to discuss his inspirations and methods, some of the hidden meanings in his work, and how he ensures that his work doesn’t echo problematic Western war imagery.

What is your typical process and how does your background in art as a social practice carry through in your work?

The topic becomes the starting point for an investigation and the medium changes, depending on what feels relevant and makes sense. I often work with people actively. For example, I shot one video at a gun shop in Skowhegan, Maine, with two guys—Bruce and Bailey. They read a text of political theory.

So, there’s a kind of working with people, collaborating with others, to create a particular work. And even with the mosaics, I collaborated with master mosaicist Abdel Moneim Barakat. He left Syria in 2011 and he’s been living in Lebanon since then.

You’ve mentioned that you fit the medium to the idea that you have. What was it about the idea for this project that led you to use mosaics as a medium?

The medium comes after the idea. But sometimes they go hand in hand, and the mosaics project is a good example. The project started in 2015 when I read an article about a group of men who were dubbed “Syria’s Monuments Men,” and they were a group of men who were working at the Ma’arat al-Numan Museum, not far from Idlib in Syria. The museum was being bombarded and attacked by the regime. They had worked there for many years, so they wanted to keep these pieces from being destroyed.

I was put in touch with one of the guys who was responsible for the preservation efforts there. His name was Abou Farid. He shared with me his image library, and the extensive documentation that they were doing as they were protecting and safeguarding the mosaics. From there, the idea came of making new mosaics that reflect on these preservation efforts.

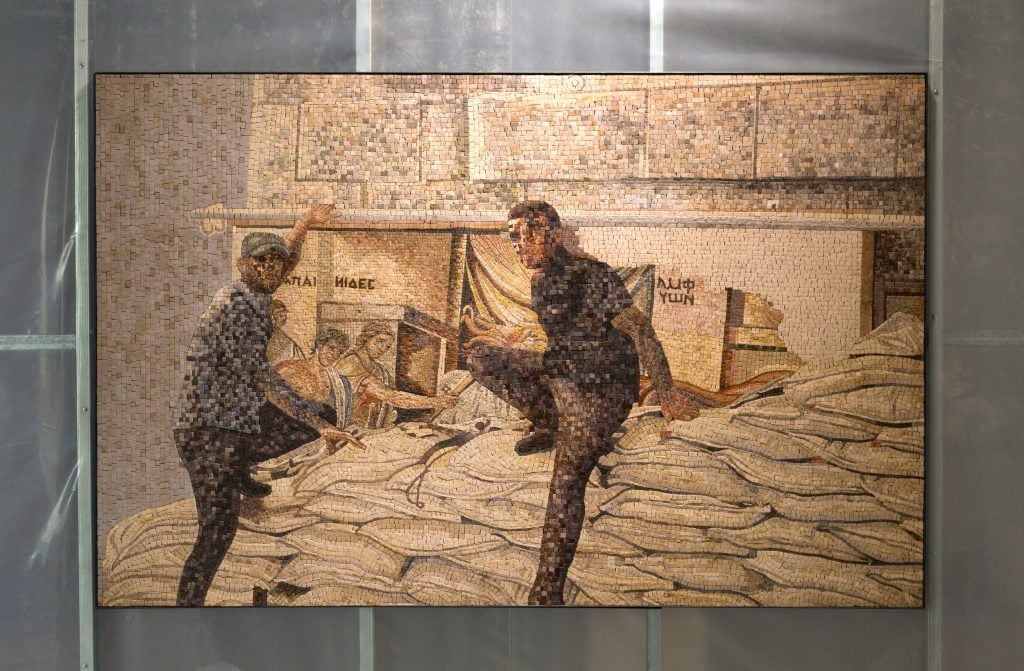

One of the mosaics is titled Ahmad and Akram Protecting Hercules. You see two men standing and sandbagging a mosaic of Hercules behind them. This mosaic was based on a photograph from that museum. These two guys were archaeologists who are kind-of anonymous individuals with quiet, heroic efforts trying to preserve Hercules.

Omar Mismar. Ahmad and Akram Protecting Hercules (2019-2020). Master Mosaicist: Abdel Moneim Barakat. Photo by Christopher Baaklini

How much is your work inspired by the old mosaics visually and what do you take from them?

Mosaics have a long and rich history outside and within the region. The braiding you see in the frames of many mosaics becomes a cropping tool you can use to highlight things in the scene. Abdel Moneim Barakat, who’s a mosaicist I work with, also worked at that museum and has skill in preservation. He knows styles such as Byzantine and Roman practices for making mosaics, and we try to emulate these as much as possible.

For example, there’s one mosaic of a lion chasing a bull—you get a lot of these hunting Mediterranean scenes in the mosaic archive, they were quite common—and so I replicate this trope. I replicate the lion and the bull, but I flip the heads. With this simple edit, I’m also trying to say something else in reversing the role of the eternal prey and the eternal predator in making these puns. So, ‘lion’ in Arabic is ‘Assad’ [like Syrian President Bashar al-Assad] and the name of bull is ‘thawr’ which phonetically resembles thawra, or revolution. So, there are these small plays that I insert into this traditional craft.

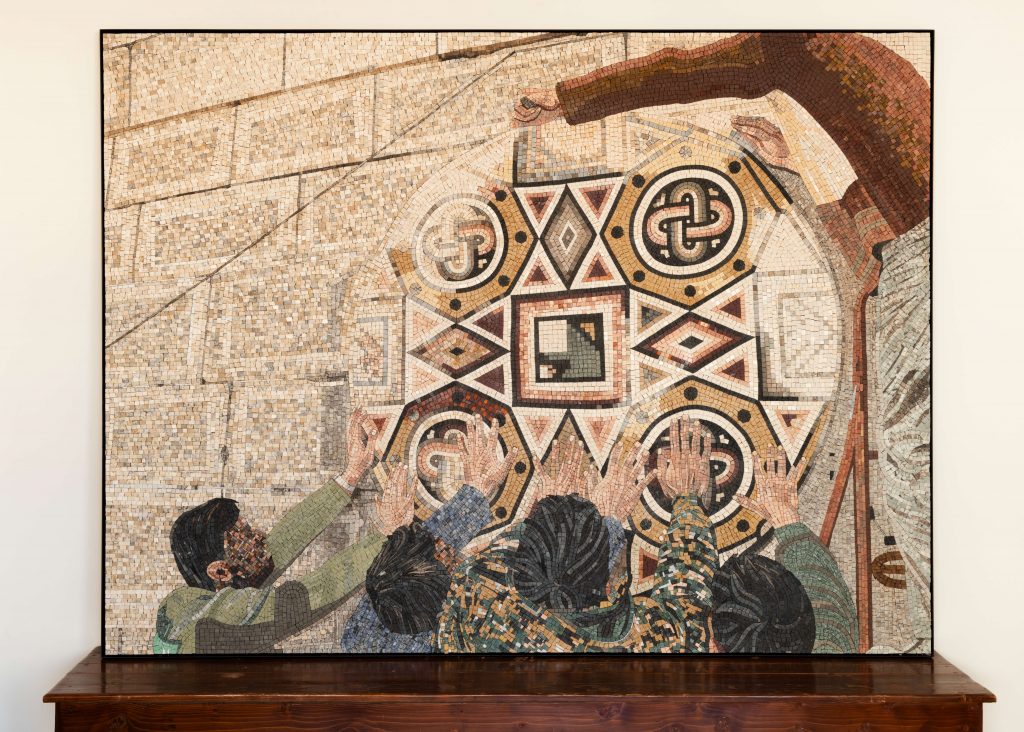

Omar Mismar, Fantastical Scene [sic] (2019-2020). Photo by Christopher Baaklini.

Has the Syrian government responded to that piece at all?

No, I feel that it’s not really on their radar. There are so many artists and people and activists working and voicefully saying true and much louder things.

How important to you are the topics that come up in your works and why do you feel drawn to expressing them?

I’m interested in the relationship between art and politics and the entanglement between the two, and what I’ve been calling the “aesthetics of disaster.” What happens when there is a particular disaster of a huge magnitude, like a war or a conflict? How does it affect us? So, in Ahmad and Akram Protecting Hercules, the fact these men were working so efficiently and in an urgent manner struck me and stayed with me. They became as important, if not more important, than Hercules, right? Hercules is the epitome of heroism and manhood, but he needed protection. But then we see these two pixelated, unknown figures trying to protect him. I like offering edits or riffs, or playing also with these kinds of narratives that we inherit, or that we get spoon-fed.

Play and humor have also become a really important element in my work, despite the somber subjects that sometimes I refer to or I work with.

A still of an image from the art documentary Abou Farid’s War by Omar Mismar showing a mosaic of a lion chasing another animal. Photo by Christopher Baaklini.

One piece we liked was this mosaic of the two men kissing. I was hoping you could tell me more about that one specifically.

That one is a departure from this other series I’ve been talking about. The “studies in mosaic” series was very much related to the work at the Ma’arat al-Numan Museum. It got expanded to include other things like Hunting Scene—which is this big, pixelated mosaic based on a YouTube still—or another one titled Spring Cleaning.

For Spring Cleaning, I produced a mosaic of polyester blankets that are common with refugees in this region. They’re bulky and warm, but very light. During springtime, they are hung on the balconies to sun and air, and they become, for me, these banners of displacement. To reproduce these blankets is an attempt at thinking of mosaics as documentation of whatever is happening. In this case, refugeehood takes center stage.

Omar Mismar, Spring Cleaning (2022). Photo by Christopher Baaklini.

I mention Spring Cleaning to tell you that, after I started with the mosaics related to the museum, I began to produce others. The Venice Biennale was an opportunity to further open up the mosaics medium to other subjects. As I researched, I became interested in subtle homoerotic moments in mosaics. I wanted to have this in-your-face, homoerotic moment for the mosaic Two Unidentified Lovers In A Mirror. I treat the faces in the mosaic as I did with others like Ahmad and Akram, where the facial features are not clear, because I wasn’t sure I could reveal who they were.

Eventually they didn’t have a problem with it, but I also realized that during one of the decrees of Yazid, the caliph of Damascus during the Byzantine Empire, there was a ban on figuration and imagery. They would keep the silhouettes of the figures in older mosaics, but they would reshuffle the stones inside the silhouettes. There was something about it that is very similar to what we have today, such as when gay men on apps or platforms cover or pixelate their faces for several reasons such as fear from persecution or wanting to remain anonymous.

Why did you begin to focus your work on Syria and the politics of the Middle East? What does that mean to personally?

The work with the mosaics and around Syria started, because for me at least, the Syrian War was too close to not affect us. I grew up in the Bekaa Valley, which is 30 minutes away from the Syrian border. We would go to Damascus often because it was closer and cheaper than coming down to Beirut. Growing up, my relationship to Syria was very much affected by my parents and the Syrian War. It was, and still is, a harsh and cruel and violent moment. When I came back from the U.S., it felt unavoidable in its proximity.

One project I did in parallel to the mosaics project was visiting Syrian refugee camps near where my parents lived and trying to take pictures there to see what I could make. I realized what I was making looked precisely like everything we’ve seen on the Syrian War. It fell into this discourse of victimization, of exoticization or celebration of the refugee as a person who can survive the violence and the atrocity, which is a problematic discourse for me. I decided not to use any of this footage or any images.

Omar Mismar. Parting Scene (With Ahmad, Firas, Mostafa, Yeyha, Mosaab) (2023). Master Mosaicist: Abdel Moneim Barakat. Photo by Mahmoud Merjan

Eventually, I made a different body of work responding to a law enacted by Bashar al-Assad, which requires people to show proof of their property in Syria within 30 days or lose their homes. Obviously, it was a law of ethnic cleansing toward people who fled. People cannot return. Some did not have property documents to prove they lived in these homes.

For me, it set off thoughts about the crisis of proof. How could you prove you’ve lived in a house for generations when it is an illegally built house or when you had to escape and leave it to save your life? I asked people to draw the floor plans of their homes as they remembered them in Syria, and I ended up with this archive that has all these floor plans, which range from the very detailed to the almost whimsical. It’s titled A Dubious Prototype.

All of this to say that I felt moved to make things about what was happening in Syria. In general, my work is really not about Syria. It happens that the mosaics project and A Dubious Prototype were about Syria. But the film I’m working on now is very much rooted in Lebanon. I had other videos on Palestine. When I was in the United States, I did the work on the gun shop.

The film I am working on now is about Botox and filler injections as a post-war aesthetic, especially in Beirut. I spent the past six months at a beauty salon filming and interacting with people. So, in that sense, for that moment in time, you could say my studio became that salon. My work feels entangled with a particular moment and place.

I’m not making my work to teach a Western audience something. People can teach themselves on their own. But I think that, if there were to be a new angle to see things, I hope it would be this possibility of different iterations and translations to things that we thought were given or guaranteed or canonized.