Studio Visit

‘There’s a Coyness’: Inside Kyle Dunn’s Symbol-Rich Cinematic Interiors

The Brooklyn-based artist's works are now on view in "Matrix 194" at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut.

Brooklyn artist Kyle Dunn paints in a studio in the basement of his home and while many artists have home studios, for Dunn, it feels particularly fitting. Over the past few years, the artist (b. 1990) has come into the spotlight with his intimate interior scenes that dramatize domestic moments.

In these homes, nude men linger in solitude; they slumber, dabble, and dress themselves in rooms filled with books, clothes, knickknacks, fruits, drinks, and ribbons. These myriad objects, one senses immediately, are symbols ripe for plucking, waiting to be unlocked the way a Northern Renaissance masterpiece is.

Interestingly, Dunn started his career as a sculptor, earning his BFA in Interdisciplinary Sculpture from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. He ultimately taught himself to paint and the shift to two dimensions unlocked new potential for the artist, along with new opportunities. Last year, Dunn opened a knock-out solo exhibition “Night Pictures” with P.P.O.W. filled with radiantly colorful nocturnal scenes. The show earned critical acclaim and marked the arrival of a new talent.

Kyle Dunn, 2024. Photograph by Jack Pierson.

Earlier this month, Dunn opened his debut solo institutional show “Matrix 194” at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut (on view through September 1). Now, he is preparing for his first solo exhibition with Vielmetter Los Angeles, which will open in the spring of 2025.

We recently spoke with the artist at his studio and Dunn shared his passion for film, Lisa Yusakavage, and the power of trompe l’oeil.

You just opened your first institutional exhibition “Matrix 194” at the Wadsworth Atheneum. For those who might not be familiar, the Wadsworth is housed in this 19th-century Gothic Revival building and has a spectacular collection of European Baroque art, making it a unique venue for contemporary art. Can you tell me how you approached the show?

Connecticut is not New York City. The museum has this amazing trompe l’oeil and still life collection and feels very old European. About half of the work is from the P.P.O.W show last year and about half is new work.

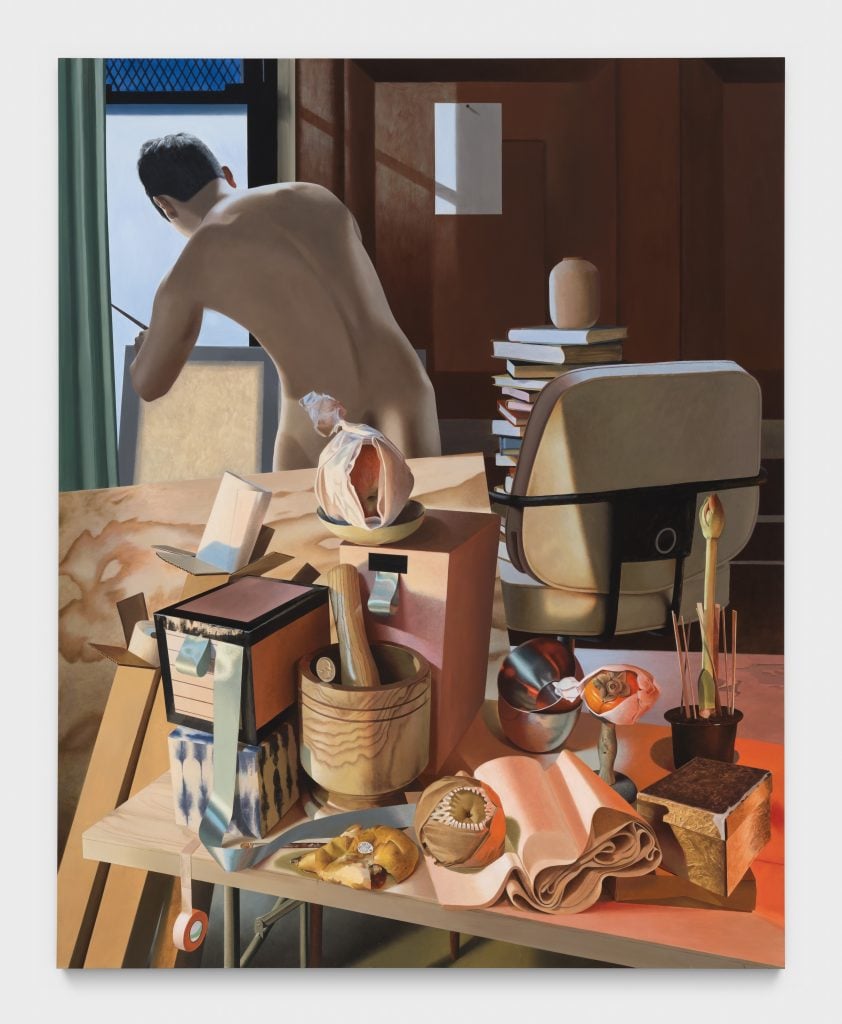

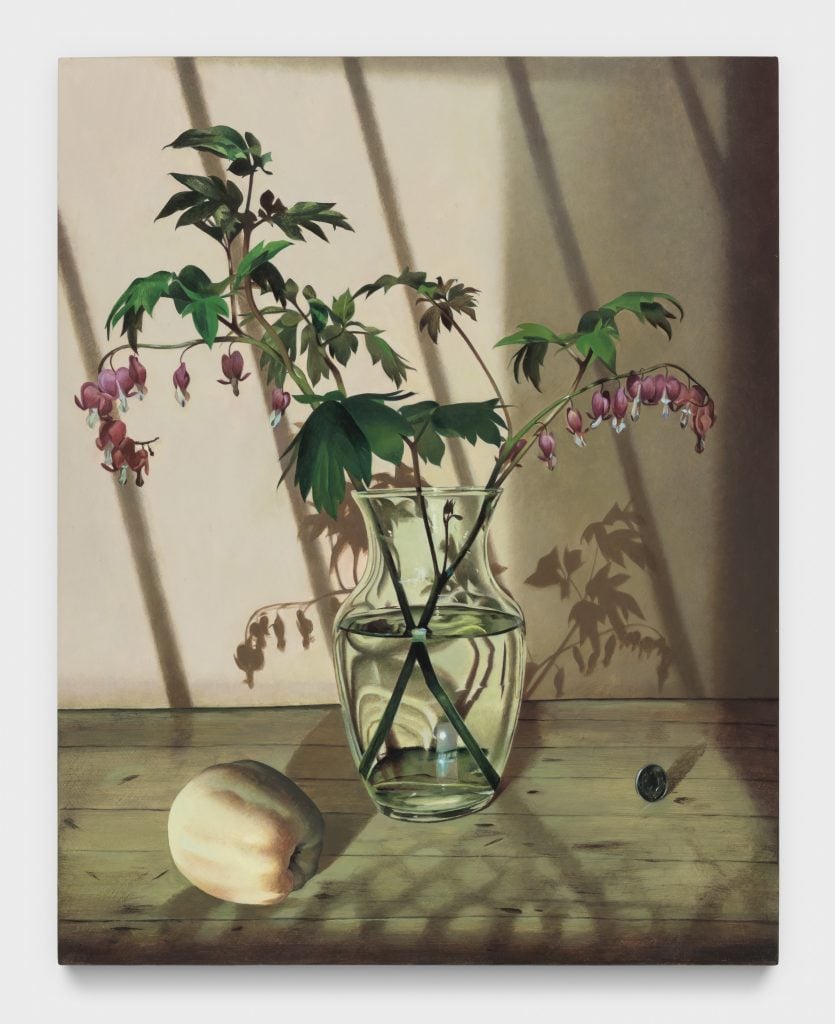

In “Night Pictures”, I used still lifes in my compositions as a way of including little Easter eggs of meaning and which moved the eye around the composition. Taking inspiration from the museum, I wanted to draw that out here.

Are there any particular “Easter eggs” in the Wadsworth show that you want to mention?

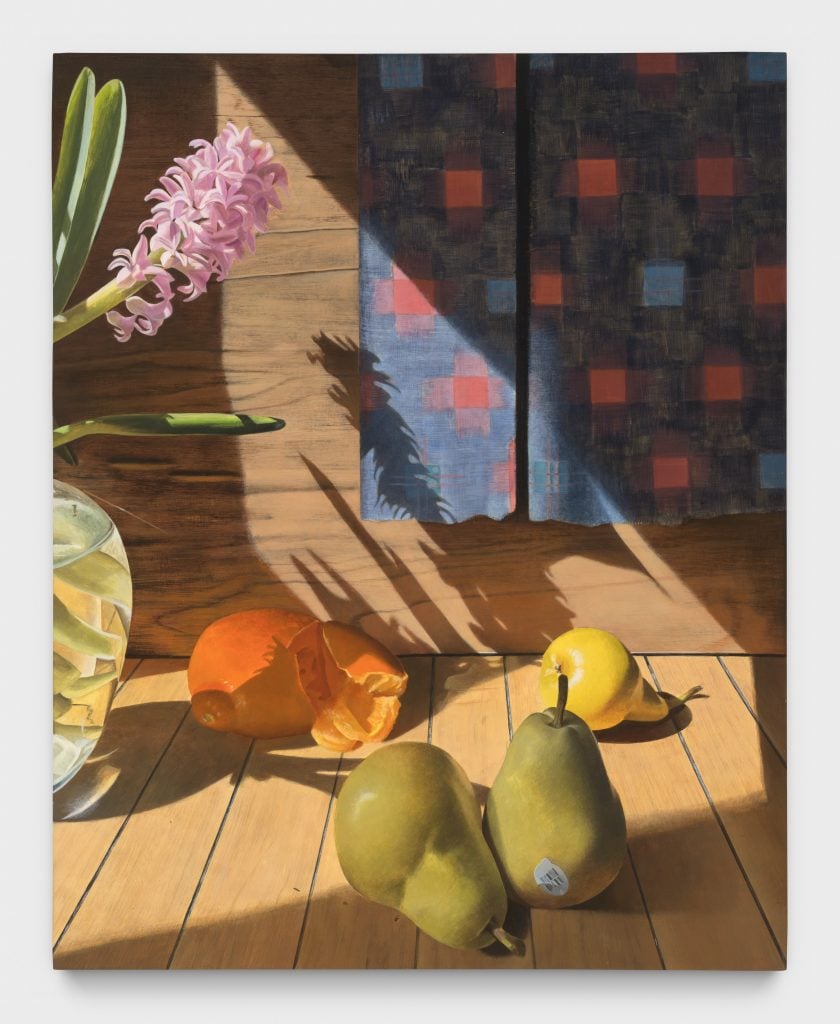

When I first went to the museum, I spent the most time with the still lifes. One painting had this starburst fabric pattern in it. The museum had taken that pattern and created a custom carpet for a gallery with the same design. I was purposely at the museum to vibe off of the collection and see what shook out. When I saw that pattern, I thought “that’s going into a painting.” The painting, Lucky Star (2024) is included in the show and has the same star theme.

Kyle Dunn, Studio Still Life (2024). Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York Photo by JSP Art Photography.

Do you have a strategy when working up to a show?

I usually work from big to small. I try to take the big swings when there’s enough time. I thrive off of stress and pressure. I dilly-dally and collect references and sketch and take photos for a long time. Too long, even. And then I paint—for “Night Pictures” I think I made five paintings in the last three months but it took two years total for the show. I need the frenzy and I need that pressure on my neck.

Describe your process. Your paintings are very meticulously planned from what I understand.

The paintings usually start with a cell phone photo. I take photographs nonstop all the time and they’re almost always built off of one small light moment—light is falling across a room a certain way. I work backward from there.

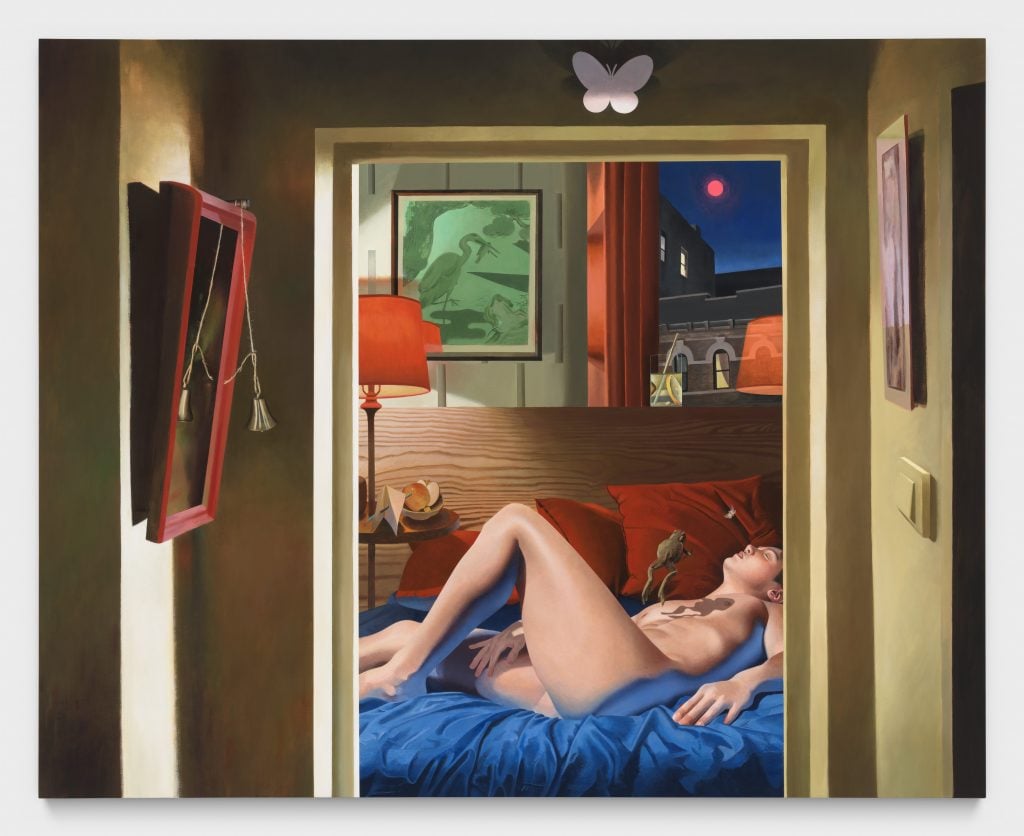

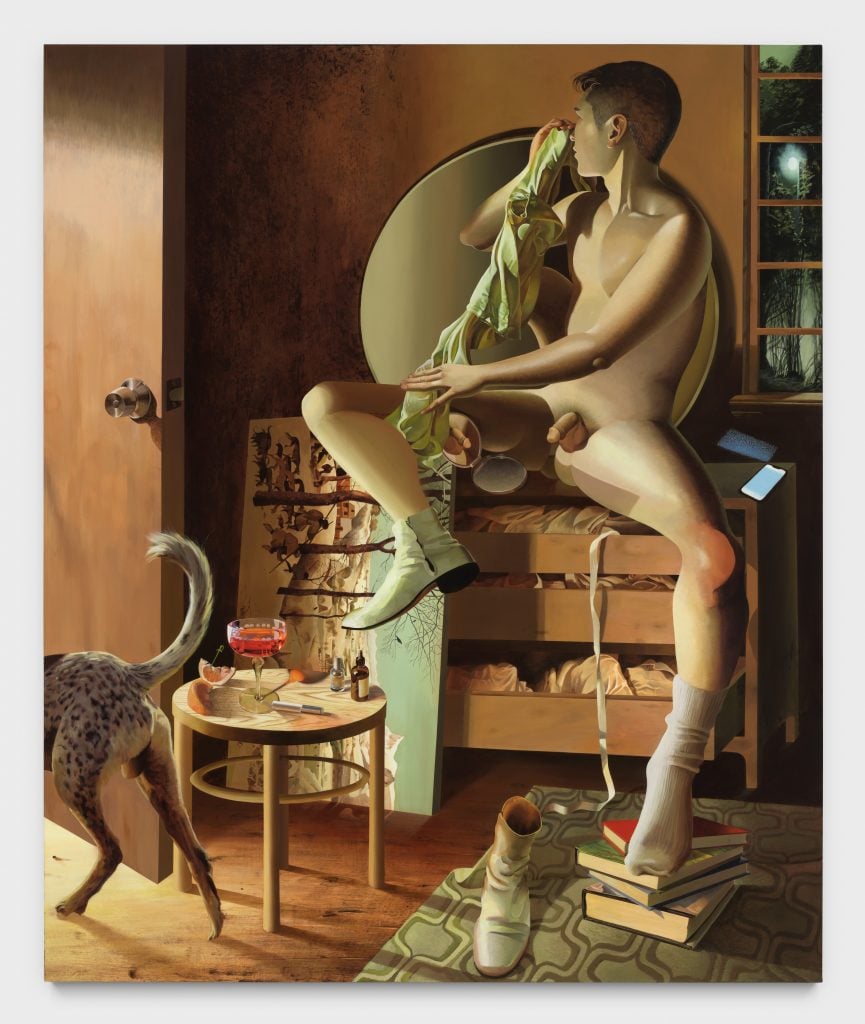

For instance, my painting The Hunt, which is in the show, started with light falling across a set of open drawers, making this sawtooth pattern. It was this nighttime light falling across an open dresser implying a sense of getting ready to go out. Meaning builds from there and as it goes along it snowballs. I suppose at the beginning it’s more open-ended and, as I work, I start nudging it along a certain track.

Kyle Dunn, Hyacinth and pears (2024). Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York Photo by JSP Art Photography.

At the risk of being too literal, how do you move from the cell phone photos, which can be quite simple, to the complex scenarios in your paintings?

I love to look at old movies by Douglas Sirk from the 1950s. Sirk was a moviemaker of melodramas. Sirk is Pedro Almodovar’s idol and his favorite filmmaker and Almodovar is my favorite artist of all time. Taking inspiration from those film sets, I start making these digital sketches from the photos I’ve taken and combining things. I stage and take all the photos myself then bring them together in a way that feels seamless. It’s very akin to collage, a cutting out and assembling process. Those collages or digital sketches are where I start my paintings.

Now that you mention Sirk and Almodovarr, I do see a cinematic quality in your paintings.

Yes, and I paint in acrylic which not many people do. Acrylic requires a certain sharpness. I use open acrylics, which dry more slowly, so I can work into the paint for longer than typical fast-drying acrylics, but they still require a certain moisturization effect.

In films, the cinematic effects of light often have harsh fields of color interacting with delineated fields of light. Similarly, I often end up structuring the paintings around these divisions of light and dark. I like the constructed architecture and environments of film sets. I also find inspiration in Japanese prints, which are great because they don’t have volumetric light.

There’s a lot of drama in interiors usually structured around evocative shadow play. It lends itself to a sense of staging.

Kyle Dunn, The Hunt (2022). Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York Photo by JSP Art Photography.

You mentioned the trompe l’oeil paintings in the Wadsworth’s collection. A lot of these types of paintings include recurring motifs—a pin in paper for instance that looks so real you think it’s an object. I see some of your paintings hinting at those too.

Yes, these trompe l’oeil paintings often use tape and ribbons as directional devices to move your eye around. Some of the works in the show make reference to John Frederick Pato, the 19th-century American trompe l’oeil painter, but mostly I was trying to put as many double entendres with the light as possible. One fruit is meant to look like an eye, a coin is about to fall, and a bloom is about to open. All these things are peeking out of the wrappings. I wanted to be as suggestive as possible while feigning ignorance, too. There is a coyness to it.

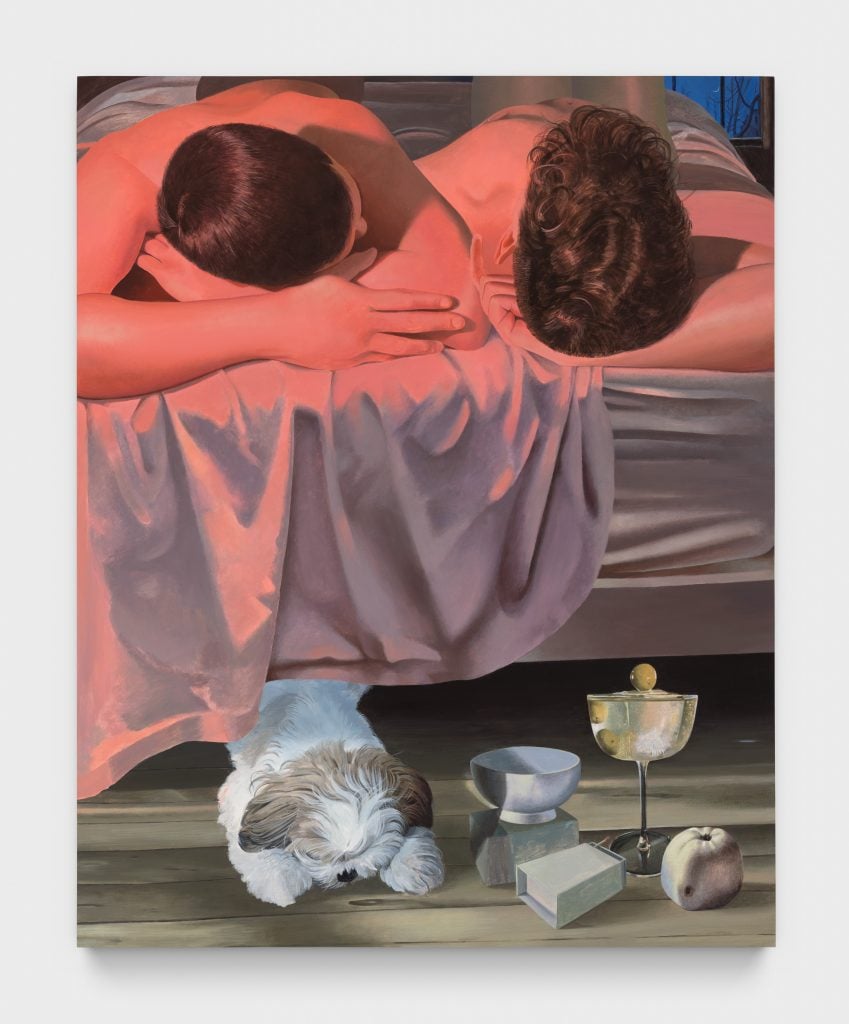

Oh, we’ve been talking so much about still lifes, but male nudes are the other central motif in your works. Do you mind telling me—who is the figure in your paintings?

Many are of my fiancé but they’re also a composite of me. The individual identity isn’t important. It’s a little photo-realistic in parts and a little synthetic.

Kyle Dunn, A Night Off (2023). Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York Photo by JSP Art Photography.

You mentioned filmmakers, but are there any artists that have shaped you?

I spent a lot of time reading a lot of interviews with Lisa Yuskavage. That changed my life. In one interview she talked about being in a used porn store and looking around at magazines. The guy next to her asked, “What are you doing in here?” And she said something like, “I’m here for the same reason you are.” It was rooted in this idea of pleasure. She said that in your work you can’t be on the outside pointing your finger at other people and scolding them. You should be implicating yourself in it too. The work has to be something that I’m guilty of as well.

I found that liberating. Paintings work in more mysterious ways. Paintings are not PSAs or political articles. They’re expressions of self-contradictory, personal, and layered experiences of life.

Kyle Dunn, Still Life with Bleeding Heart (2023). Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W, New York Photo by JSP Art Photography.

Last question, is there an ideal way for people to experience your paintings? Is there anything you want people to take away?

Paintings are, at their best, tools to make someone else feel an emotion. If it makes you feel something, that’s what I want, you know? I don’t listen to music when I’m painting ever because it makes me too emotional, but if you’ll allow me to make an analogy to types of music, I’d be a singer-songwriter.

In the same way that the songs are informed by personal biography, but also can become cultural touchstones, I want my paintings to be experienced in the same way. I wish paintings could be used the same way that songs are—a painting for a great day at the beach, a painting for crying and grieving, something you can carry in your back pocket.