Archaeology & History

30 Years After the Discovery of Ötzi, the ‘Iceman’ Mummy, New Research Rewrites How He Died and How He Was Preserved

A new study challenges the long-held Ötzi narrative, claiming that he did not die where he was found.

A new study challenges the long-held Ötzi narrative, claiming that he did not die where he was found.

Richard Whiddington

Since Ötzi the Iceman’s discovery in the Italian Alps 30 years ago, no mummy has been more extensively studied and analyzed. In fact, the 5,000-year-old man is widely credited with launching field of glacial archaeology itself. Scientists know his eye color, blood type, bodily discomforts (intestinal parasites, cavities, Lyme disease), and that his final meal was einkorn wheat, deer, and ibex. Still, research into the Iceman continues.

A recent paper in the Holocene rewrites the story of how Ötzi came to lie in the Tisenjoch pass gully where he was found by hikers in 1991. Previously, researchers claimed the man had quickly been covered by glacial ice after being killed by an arrow shot. His existence, the thinking went, was serendipitous, the discovery extremely rare. The new study proposes that Ötzi didn’t die in the gully, but rather was carried there by ice that thawed and froze over the course of many years.

“Our study indicates that Ötzi was not preserved by a series of lucky circumstances, but by normal natural processes on ice sites,” Lars Pilø, lead author on the paper, told Artnet News. “This suggests that there may be a greater chance for the preservation of more ice mummies than previously believed.”

Window looking into the Iceman’s refrigerated cell. Photo: © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology/Ochsenreiter

The first step to countering the established Ötzi narrative involved demonstrating that the man died not in autumn, as previously suggested, but in spring or early summer. The paper brings forth previous research that shows the presence of hop hornbeam pollen in Ötzi’s gut and fresh maple leaves at the site, both of which indicate he likely died in May or June. Such timing means Ötzi was surrounded by snow when he died and his body was moved by a heavy melting situation or a series of smaller melting events. Eventually, he moved to the gully and was covered by a field of non-moving ice.

“As my knowledge of how ice sites work increased, it became clear that there was something wrong with the original theory,” Pilø said. “Some preconditions need to be fulfilled for mummies to preserve in the ice. The person needs to die on ice that does not move, and the body cannot be recovered by relatives or others.”

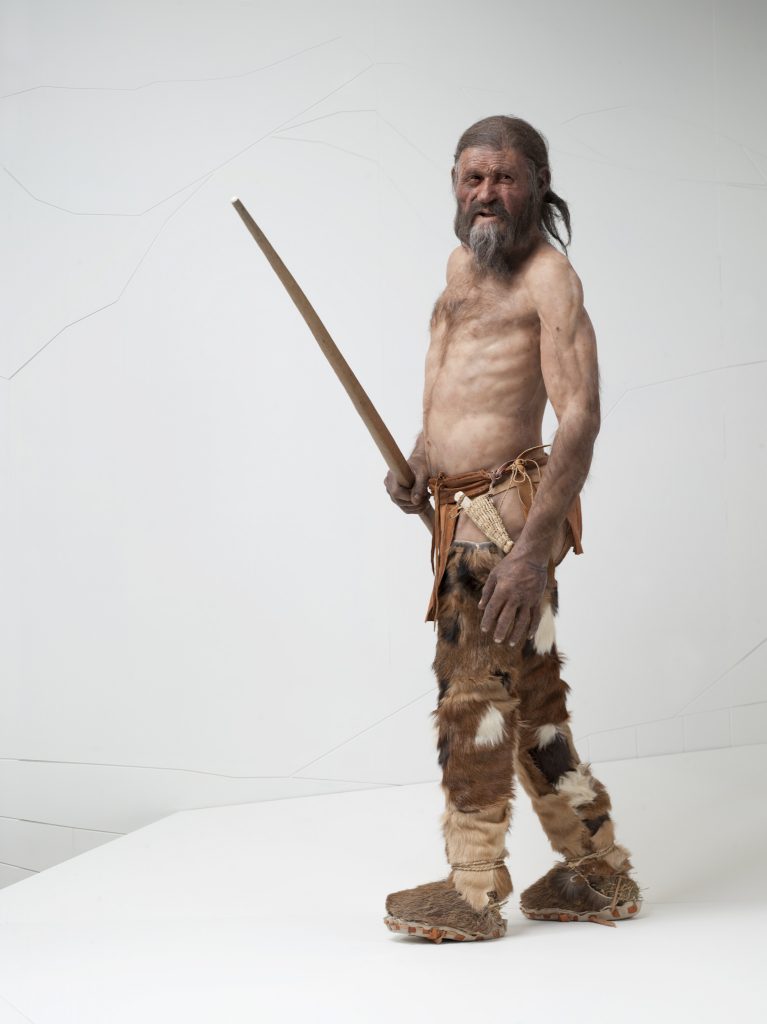

Reconstruction of the Iceman by Alfons & Adrie Kennis. Photo: © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology/Ochsenreiter

Another challenge to the established narrative involves Ötzi’s artifacts, which were previously believed to have been damaged during combat. Instead, the Holocene paper argues, they were cracked and broken by the pressure of snow and ice.

Much of the research from the past three decades has focused Ötzi’s find spot and its immediate surrounding; now, Pilø suggests, it’s time to conduct an archaeological survey of the pass itself. An investigation into the remaining ice could bring “interesting results,” Pilø said.

Ötzi is displayed at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where an average of 300,000 people visit each year.