Archaeology & History

This Is the Story of the Artist Who Has Made a Career Tattooing Herself Like Europe’s Famed ‘Iceman’ Mummy

The artist used her own blood.

The artist used her own blood.

Sarah Cascone

When is a tattoo parlor the perfect venue for a contemporary art show? When the art on view is Nicole Wilson’s nearly decade-long project “Ötzi,” in which she recreated each of 61 tattoos found on the over 5,000-year-old Ice Age mummy of the same name on her own body, using her own blood in lieu of ink—and documented the healing process, photographing as the marks slowly faded away.

Archaeologists discovered Ötzi the Iceman in 1991 in the Ötztal Alps on the Italian-Austrian border. He had died circa 3230 BC—likely murdered—but his body was remarkably intact, the oldest naturally occurring mummy ever found in Europe. (He’s now housed at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Italy.)

“I like to say he was preserved due to cataclysmic circumstances—a perfect storm of him dying as a storm came through, covering him in snow and ice that perfectly preserved his body,” Wilson told Artnet News. “He’s a mummy, but not in the same way as Egyptian mummies. He wasn’t prepared for death in any way.”

The artist, who is 33, remembers learning about Ötzi as a young child, shortly after his discovery, and questioning her teachers’ assertions that the Iceman was her ancestor. As an adult, she became captivated by his mysterious tattoos, 15 groupings of 61 lines that mark various parts of his body. (Ötzi’s prehistoric tattoo artist rubbed pulverized charcoal into cuts in his skin, rather than using ink.)

Ötzi the Iceman. Photo by the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology.

“The tattoos themselves are super interesting,” Wilson said. “Scientists think they might have acupuncture significance, but we don’t actually know. We can’t ask what the lines and the dashes and hashes meant to this person.”

The idea of replicating those marks became a fixation for the artist.

“I started to become really obsessed with this idea of matching myself to history,” Wilson recalled. “If I could be a proxy for his body, or vice versa, what would that mean? It’s about closing some kind of historical time warp, as if we could compress time.”

The physical display features the photographs of the tattoos, but collectors can also buy digital files for each tattoo that have been authenticated and registered on the blockchain. (The South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology has given Wilson its permission.)

Nicole Wilson, “Ötzi”. Photo by TJ Proechel, courtesy of Nicole Wilson.

The purchaser can buy just one of the 15 tattoo groupings, which range in price from $400 to $1,800, based on complexity—Wilson wanted to keep the pricing somewhat in line with traditional tattooing—or get the whole set for $10,000.

The editioned design files come with instructions for tattooing, with Wilson likening it to purchasing a Sol LeWitt wall drawing. Because the lines in each tattoo are so simple, each grouping takes maybe ten minutes or so to ink—a process that several collectors have already done, Wilson said. (She estimates that getting the full set done with tattoo artist Matt Moreno took less than two hours.)

Matt Moreno tattooing the Ötzi tattoos on Nicole Wilson at Three Kings Brooklyn. Photo by TJ Proechel, courtesy of Nicole Wilson.

She first got the Ötzi tattoos done in 2012, enlisting a friend with a tattoo gun to do the honors. Wilson used blood because she wanted to literally absorb the ancient mummy’s marks. As expected, her skin reabsorbed almost all the blood immediately, but as her skin healed, the heme (the pigment within blood) left dark scars from post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. The physical healing process started off dramatic, but then grew more gradual as time passed.

Over the next four years, Wilson photographed her body as the marks grew fainter and fainter, before disappearing altogether. (Much of the experience for her was about living with the scars, and explaining them to people who wanted to know where they came from.)

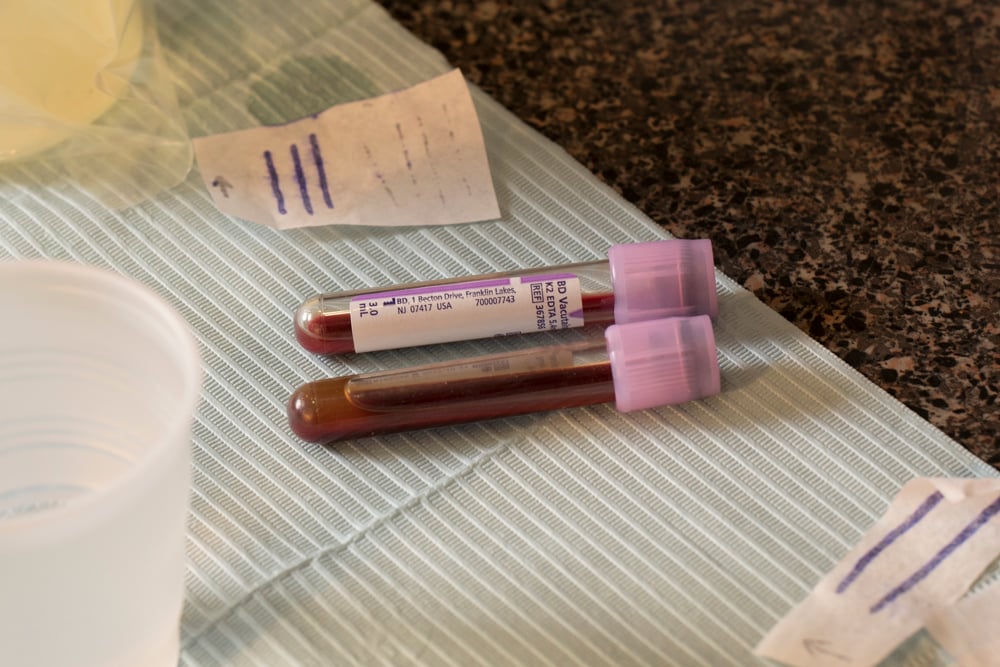

Nicole Wilson’s blood, used to “ink” the Ötzi tattoos on her body. Photo by TJ Proechel, courtesy of Nicole Wilson.

“It’s interesting to live with marks on your body. You look down when you’re getting dressed, and are reminded of what you did and that connection that you’re trying to make. For years, I was thinking a lot about who I am and my relationship with history,” Wilson said. “It was a little sad for them to disappear completely.”

Then, in 2015, experts using multispectral photographic imaging found two more tattoos on Ötzi’s body. Wilson decided to start all over again—this time, enlisting a professional tattoo parlor.

“Trying to find a tattoo shop that would take me seriously may have been one of the most discouraging points in my whole career,” Wilson said. “But I was really committed to this feminist action I was making—I saw myself calling up my feminist performance art heroes.”

Even though she had spoken to medical experts and dermatologists about tattooing in blood—and had in fact already done it successfully, tattoo parlors turned Wilson away time and time again. Fortunately, Three Kings Tattoo, a studio with locations in New York, Los Angeles, London, and North Carolina, was intrigued by the project. Not only did they agree to participate, they offered to host a show about the project following its completion.

Years later, after the tattoo markings had faded once again, Wilson’s “Ötzi” exhibition debuted at Praise Shadows Art Gallery in Boston in May. It’s currently on view at Three Kings Brooklyn’s Greenpoint location, and will travel to the shop’s Los Angeles and London outposts in 2022. But the artist stressed that she isn’t aiming to draw a parallel between modern tattooing and the prehistoric practice.

“The easy answer is that our ancestors had tattoos too, so we’re not so different. That’s not what I’m trying to do with this project,” Wilson explained. “I’m trying to speak with the gaps in what we know and who we are. So much of history ties itself up so neatly, but we need to talk about what’s missing and what gets left out—the gaps in history that are also making our contemporary stories today.”

“Nicole Wilson: Ötzi,” organized by Praise Shadow Art Gallery, Boston, is on view at Three Kings Brooklyn, 572 Manhattan Avenue, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, October 23–November 20, 2021. It will travel to Three Kings Los Angeles and Three Kings London in 2022.