Archaeology & History

Scientists Digitally Undressed a Legendary Mummy King to Offer an Unprecedented Look at His Face, Body, and Jewelry

The pharaoh died when he was just 35 years old.

The pharaoh died when he was just 35 years old.

Caroline Goldstein

Scientists have managed a feat they once thought impossible: peering beneath the layers of linen that once swathed the mummy of King Amenhotep I. And they didn’t even have to unwrap him at all.

Millions saw the mummy’s countenance when it was used as the icon for the “Royal Golden Mummy Parade” in March 2021. Its body was transferred to Cairo’s new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization a month later, along with 21 other royal mummies. But until now, the secrets the king took to his grave around 1504 B.C. remained under wraps.

Led by professor Sahar Saleem, a radiologist at the University of Cairo, the team used CT scans to digitally undress the royal mummy. The findings were published in the December 2021 edition of Frontiers in Medicine.

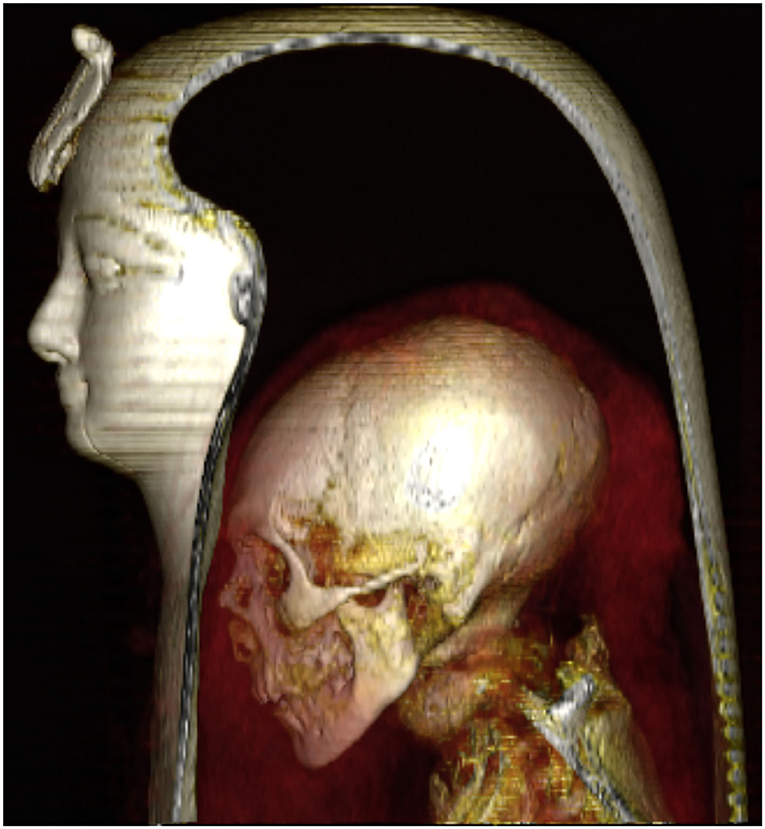

Three-dimensional CT image of the head of the wrapped mummy of Amenhotep I in a left lateral view allows visualization of the component layers: the mask, the head of the mummy, and the surrounding bandages. Courtesy of S. Saleem and Z. Hawass.

Amenhotep, a warrior king whose name means “Amun is satisfied,” ascended the throne following the death of his father, Ahmose I, in the 18th dynasty, and ruled from ca. 1525–1504 B.C. He peacefully protected the territories of Egypt during his reign and commissioned many temples, including at Amun at Karnak, Thebes, which served as the center of worship to the god Amun-Re during the New Kingdom.

When King Amenhotep I was found in 1881, in Luxor, researchers learned from decoding hieroglyphics that his mummified corpse had been unwrapped and re-wrapped by priests in the 11th century at the burial site (which was known as a hiding place for royal mummies, and a target for tomb robbers). Some scholars have suggested that the priests were themselves opportunists who would steal jewelry from the tombs of royal mummies, but the research team’s findings disprove that.

“We show that at least for Amenhotep I, the priests of the 21st dynasty lovingly repaired the injuries inflicted by the tomb robbers, restored his mummy to its former glory, and preserved the magnificent jewelry and amulets in place,” Saleem told The Guardian.

The pharaoh’s skull, including his teeth in good condition. Courtesy of S. Saleem and Z. Hawass.

The CT scan generated two- and three-dimensional images of the mummy’s skeleton, although some areas were hard to penetrate using the 3D model, because layers of floral garlands obscured the chest area. Digitally peering through the painted wood mask covering the mummy’s face, scientists deduced that it was oval shaped, with deeply-set eyes, a small flat nose, narrow chin, and small ears with one small piercing. He stood about five feet and six inches tall, and although the CT scan did not reveal any specific cause of death, the scientists noted that the king was approximately 35 years old when he died. He had 30 amulets wrapped with him, including a gold beaded girdle.