Art History

Self-Taught Artist Ovartaci Made Fantastical Creations in a Psychiatric Hospital for Over 50 Years. Now They’ve Found a Home in the Art World

The artist has remained largely unknown outside of specialized circles.

The artist has remained largely unknown outside of specialized circles.

Katie White

In the course of 56 years living in a psychiatric hospital in the small city of Risskov, Denmark, a self-taught artist born Louis Marcussen (1894–1985) christened themselves anew as Ovartaci.

The moniker translates roughly to Chief Loon, and was a winking nod to the hospital’s hierarchy of doctors (Chief Physician, for instance) as well as to the artist’s unique identification within the hospital microcosm within which they lived and created for most of their life.

Indeed, it was within those hospital confines that Ovartaci began their artistic journey in the 1930s and it was there it would end with the artist’s death at the age of 91. During the intervening decades, the Danish artist devoted themselves to creating a chimerical and wholly unique world, filled with women and animal figures, often melding species together into mythical and majestic creatures.

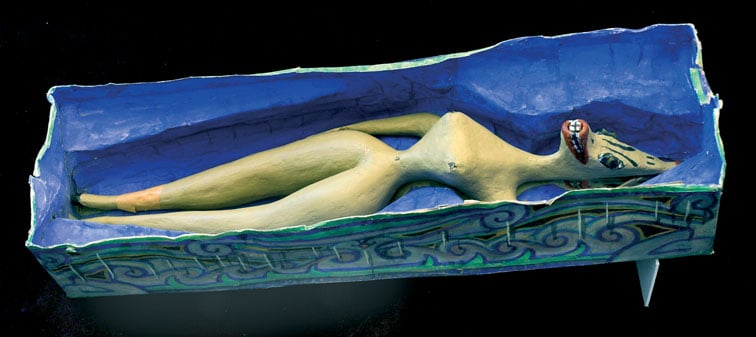

The artist worked in drawing and painting, even making a number of handmade dolls that filled their hospital room. Marked by allusions to ancient and mystical societies, these hybrid beings were influenced most pronouncedly by Ancient Egyptian: its mythology, hieroglyphs, art, pyramids, and, perhaps most centrally, its beliefs in the transcendence of the soul. A cat-woman frequently appears in these works, too, a likeness that conjures up ready comparisons to the goddess Sehkmet.

Ovartaci, Large Doll. Courtesy of the Ovartaci Museet.

Yet Ovartaci has remained largely unknown outside of specialized circles since the artist’s death in 1985. Now, however, the artist’s fascinating creations are primed for a wider appreciation, as a number of Ovartaci’s works are currently on view in “The Milk of Dreams,” the curated exhibition at the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale.

In an exhibition statement, curator Cecelia Alemani noted that “the mutant bodies convoked” by artists including Ovartaci “suggest new mergers of the organic and the artificial, whether as a means of self-reinvention or as a disquieting foretaste of an increasingly dehumanized future.”

Indeed, Ovartaci’s artistic world seems prescient of a future even still yet to come, and the works themselves are only further illuminated by the artist’s life story.

Identified as male at birth, Ovartaci had trained as a house painter, leaving Denmark in 1923 for work in Argentina. Wandering that country for six years, Ovartaci returned to Denmark both physically ravaged and mentally distraught. The artist’s family had them committed to a psychiatric hospital in 1929.

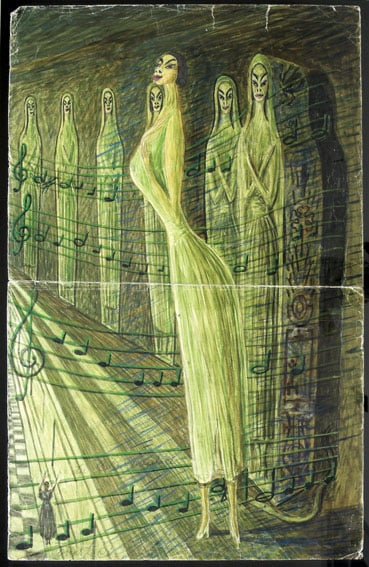

Ovartaci, Musikkvinder. Courtesy of the Ovartaci Museet.

In the Risskov hospital, Ovartaci began to develop a belief system that would fuel artistic experimentations. During these years, the artist committed themselves to Buddhism and a belief that the soul traveled and reincarnated across countless lives, unencumbered by confines of culture, gender, or species. The artist detailed what they believed to be their own past life existences as a tiger or an ancient Egyptian working on the pyramids.

By the 1950s, Ovartaci began to identify and live as a woman and repeatedly entreated the hospital for gender reassignment surgery. In 1951, after the request was refused, the artist made their own crude attempt with carpenter’s tools, a harried act that needed medical treatment and sunk the artist into a depression.

Eventually, as hospital policies shifted, Ovartaci’s gender confirmation surgery was completed in two parts in 1955 and 1957. The artist was also moved to a private room and given access to a studio where their creations proliferated. (In the last years of their life, Ovartaci began to again identify as male.)

Ovartaci, Sarcophagus Open with a Doll. Courtesy of the Ovartaci Museet.

Ovartaci’s creatures are not meant to be monstrous, but elegant and distinctive, and they presage the idea of identity as existing in a state of continuous flux. Oftentimes, the hospital appears in the artist’s works as a complex reference: the artist fought against the confines of hospital life but simultaneously found creative freedom in its domain.

When Ovartaci died at the age of 91, the Risskov psychiatric hospital was left in possession of countless creations. Today, many of those works are in the Museum Ovartaci, an art and historical museum that encompasses the historical Risskov Psychiatric Hospital and devotes itself to the art produced by patients of the hospital. (The museum lent numerous works for display at the Venice Biennale.)

Although many commentators have cast Ovartaci as an Outsider artist, Mia Lejsted, the director of the museum, thinks the characterization is too limiting for the artist’s complex reality.

“We never use the term ‘Outsider artist’ to describe Ovartaci here at the museum,” Lejsted said. “It does not matter whether you are ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the art world, and perhaps Ovartaci is showing us a third place to be.”