Market

The Triumph of Ultra-Contemporary Art: How the Desire for the New Is Transforming the Market

Auction sales of works by young artists have spiked 305 percent since 2019.

Auction sales of works by young artists have spiked 305 percent since 2019.

Artnet News and Morgan Stanley

A version of this article originally appeared in the Artnet News Pro spring 2022 Intelligence Report.

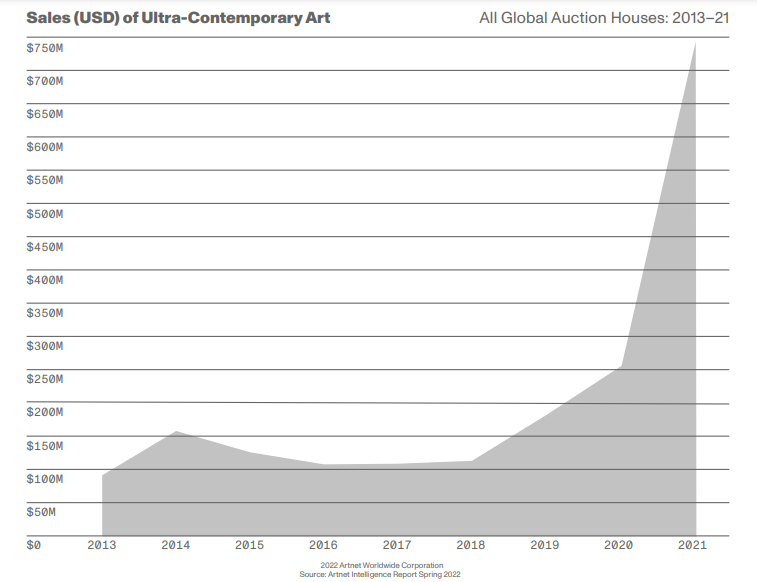

One segment of the art market is growing faster than all the rest: ultra-contemporary art. Auction sales in the category—which refers to work made by artists born after 1974—did not merely continue climbing during the pandemic, rather they exploded, spiking 305 percent from 2019 to 2021.¹ A closer look at this niche brings insight and visibility to the youngest talents with strengthening secondary markets.

In collaboration with Artnet, Morgan Stanley will explore what’s behind the unprecedented growth in demand for new art. First, we’ll illustrate how the market has grown, which regions are showing the way, and which artists are leading the pack, using data from the Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics.

Then, we’ll take a look at various participants in the art market beyond auctions to see how galleries, art fairs, museums, artists, and collectors are seizing this moment as an opportunity to reach new audiences in new ways.

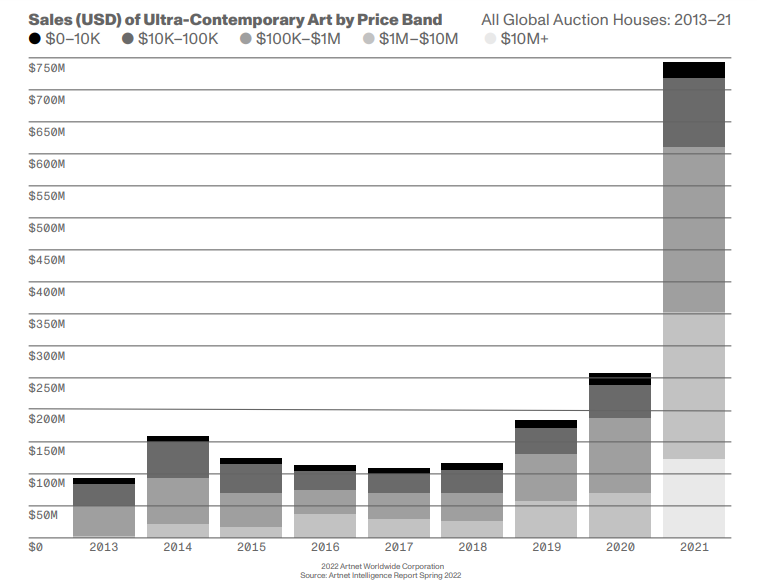

Although ultra-contemporary established itself as a fast-growing category during the last decade, the past two years of auction market activity have propelled it to new heights. The genre’s previous peak took place across 2013 and 2014, when worldwide sales increased from roughly $91.8 million to just under $159 million. The next few years saw a relative lull. The major change took place during the pandemic: after rising to $183.4 million in 2019, auction sales of ultra-contemporary artworks swelled by roughly 40 percent year over year to $256.4 million in 2020, then nearly tripled, to $742.2 million last year. Driving this activity were a number of factors that we will explore in the upcoming charts.

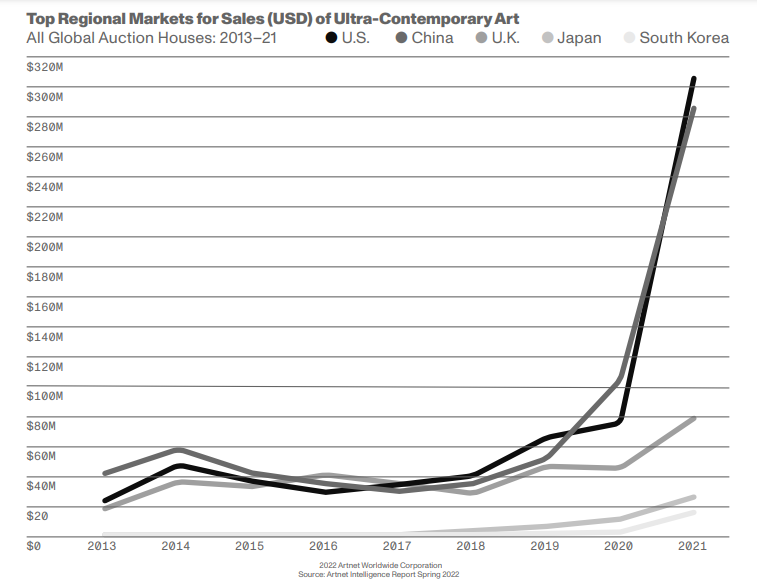

One of the more remarkable aspects of ultra contemporary art’s recent surge has been its overwhelming concentration in just two regional markets. During the previous peak, in 2013–14, the U.S., U.K., and China all contributed fairly equally to the category’s success; no more than about $22 million in sales separated the third-place British market from the first-place Chinese market in either year.

The story changed dramatically in the past two years. In 2020, the gap separating third-place

U.K. auctions from first-place Chinese auctions rose to nearly $60 million, almost triple the discrepancy between the two regions during the category’s previous market peak. In 2021, the gap between sales of ultra-contemporary works in the third-place British and first-place U.S. auction markets increased even further, to an astonishing $225 million. The U.S. and China together generated almost $589 million in sales in the category that year, with less than $19 million worth of sales separating one from the other. On their own, each country’s 2021 total sales surpassed all worldwide sales of ultra-contemporary artwork in any previous year on record.

All other regional markets were essentially accessories throughout this eight-year period. Japan, which had the fourth-highest auction sales of ultra-contemporary art in 2021, contributed less than 2 percent to the category’s global total that year.

The growth in sales of ultra-contemporary art at auction has obeyed the precepts of art sales at auction in general: the greater the overall value of sales, the higher the concentration of sales in the uppermost price brackets. The previous peak, in 2014, doubled as the first time individual ultra-contemporary works sold for between $1 million and $10 million. Once the genre crossed that threshold, however, it has not gone a single year without at least one sale in that previously unprecedented price bracket.

Between 2015 and 2020, the only change to the category came in the total dollar value of sales within each of the four price brackets already achieved. Notably, the considerable rise in 2019 and 2020 corresponded to the largest uptick in sales in the two highest price brackets at the time. From 2018 to 2019, total sales more than tripled in both the $100,000-to-$1 million and $1 million-to-$10 million bands; from 2019 to 2020, total sales more than doubled from their previous highs.

It’s only fitting that the all-time high in ultra-contemporary art sales coincided with the genre’s introduction to the “trophy lot” price bracket above $10 million. In 2021, the genre generated about $122.7 million worth of sales in this territory, en route to a worldwide total of nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars. Notably, all sales in this top bracket were of non-fungible tokens (NFTs): works by Beeple, the creators of Bored Ape Yacht Club, and the creators of CryptoPunks.

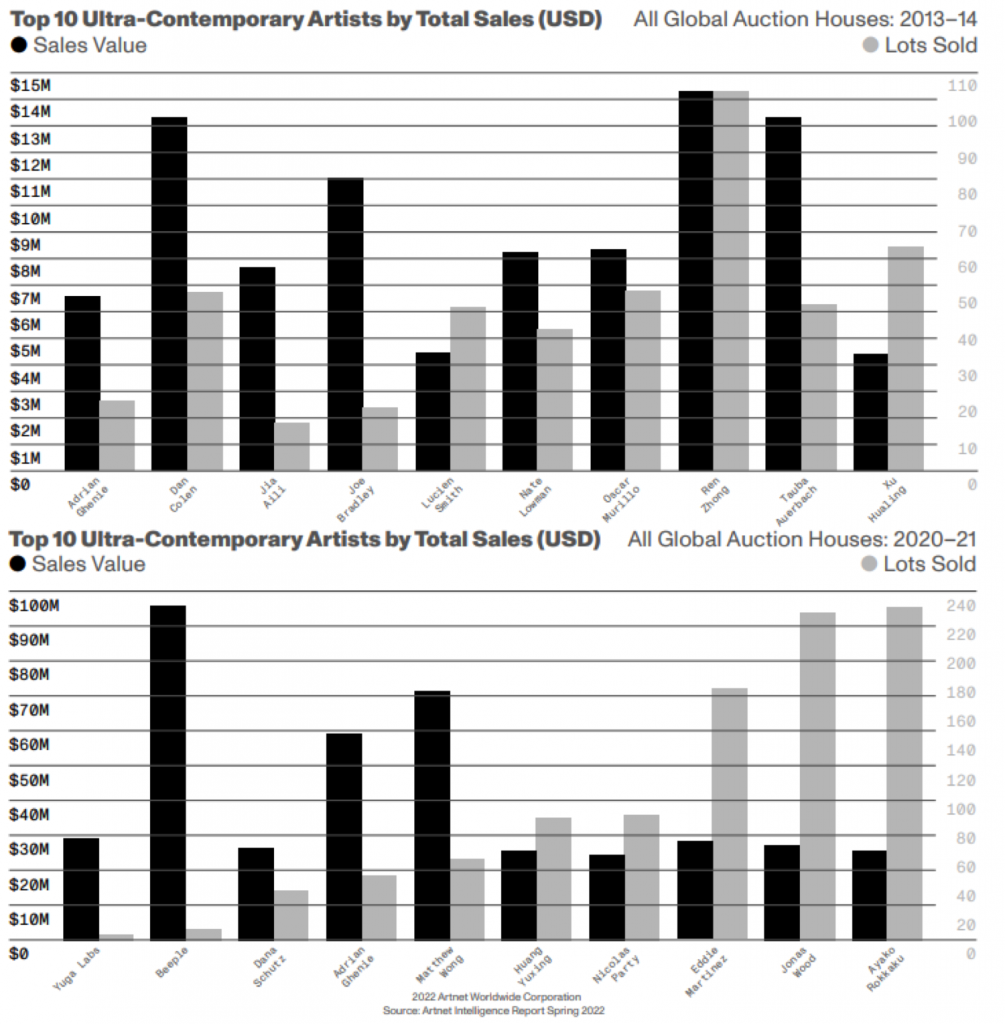

When comparing the 2013–14 spike in ultra-contemporary art sales with the 2020–21 peak, one other factor deserves attention: the two rises derived from demand for two almost entirely different sets of artists. Of the top 10 artists by sales value in each two-year period, only Adrian Ghenie appears on both lists. This comparison speaks to a larger change in taste that has contributed to the rise of ultra-contemporary art, which we will explore.

The increased focus on young artists is perhaps most pronounced in the auction sphere—but it has touched nearly every part of the art world, from art fairs and galleries to collectors, artists, and museums. Below, we shine a spotlight on various participants in the industry to examine how each has shifted in an effort to foreground new art, attract new audiences, and make room for innovation.

As evidenced by the charts in the previous section, ultra-contemporary is the fastest-growing segment of the art market at auction. The top three auction houses—Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips—generated $572.8 million from ultra-contemporary art in 2021, up a whopping 222 percent from 2020.² (These figures include both traditional media and NFTs.)

Christie’s—which has embraced the sale of NFTs most enthusiastically of the three houses—is strongest in the ultra-contemporary category, with $282.2 million in annual sales. Sotheby’s follows with $167.3 million; Phillips comes in third with $123.3 million.³

In a sign of just how important the market for young art has become, Sotheby’s launched a new marquee sale in New York in November called “The Now,” specifically dedicated to art made within the past few decades. It marked the first time an evening sale had been devoted to this category. The 23-lot auction made $71.8 million.4

While the market darlings of the previous young-art boom in 2013 and 2014 were primarily men who specialized in process-based abstraction (dubbed “Zombie Formalists” in the art press5), a large proportion of today’s fast-rising stars are women and artists of color who produce figurative painting as well as new-media artists. Of the top 25 ultra-contemporary artists at auction in 2021, nine were women; 10 were artists of color (two of whom are female).6

Another prominent area of growth is auction sales of work by ultra-contemporary African artists. They have increased 434 percent over the past two years, to almost $40 million in 2021 from $7.5 million in 2019.7 Leading figures include Cinga Samson (b. 1986), whose Two piece 1 sold for $378,000, more than 10 times its high estimate of $35,000 at Phillips in June, and Ismail Isshaq (b. 1989), whose Unknown Faces 8 soared to $275,000 against an estimate of $15,000 to $20,000 at Christie’s in December.8

The industry’s largest art fairs have traditionally focused on showing the work of younger artists—but in recent years, they have made changes in an effort to ensure that they remain a place for discovery. In 2018 and 2019, Art Basel, Frieze, FIAC, and other fairs introduced new progressive pricing systems for booth fees, as well as other discounts, to ease the burden on young galleries.9

Art Basel Miami Beach also hosted a special section dedicated to NFTs for the first time in 2021. Furthermore, the fair revised its rules about who can participate. There is no longer a minimum age requirement for galleries to apply (previously, galleries had to be at least three years old). Applicants are also no longer required to have a permanent space or stage a set number of exhibitions per year (provided they do, in fact, stage shows).10

These changes are designed in part, organizers said, to increase the diversity of exhibitors (and therefore of the artists on view and the clientele in the aisles). Historically, Art Basel Miami Beach had admitted very few Black-owned galleries and almost no galleries from Africa. The 2021 edition marked the debut of four galleries owned by Black Americans, three from Africa, eight from Latin America, and one from Korea.11

Smaller regional fairs are also targeting young art and collectors. Singapore’s S.E.A. Focus fair intentionally kept prices low this year (starting at $650).12 Art X Lagos launched a new section in partnership with an NFT marketplace for its 2021 edition that highlighted the growing digital art scene on the continent.

Mega-galleries long associated with established, blue-chip artists have added numerous younger names to their rosters over the past three to four years. Pace has taken on Loie Hollowell (b. 1983), Robert Nava (b. 1985), and Marina Perez Simão (b. 1981). The gallery also hired Kimberly Drew, an art-world social media expert, to increase its outreach to young artists.13 And in November, its new online sales director, Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle, launched an NFT platform that produces digital projects with contemporary artists.

Gagosian has so far steered clear of NFTs, but it hired curator and writer Antwaun Sargent, who has begun a program of shows by young Black artists including Awol Erizku (b. 1988), Alexandria Smith (b. 1981), and Amanda Williams (b. 1974), marking the Gagosian solo debut for each. The gallery also represents ultra-contemporary names Nathaniel Mary Quinn (b. 1977), Titus Kaphar (b. 1976), and Jonas Wood (b. 1977).14 Hauser & Wirth has picked up its own young stars: Avery Singer (b. 1987), Angel Otero (b. 1981), and Nicolas Party (b. 1980).15

Last year, David Zwirner launched a millennial-friendly e-commerce company that seeks to expand the audience for emerging art by partnering with a select group of small and midsize galleries. Zwirner also represents Harold Ancart (b. 1980), Lucas Arruda (b. 1983), Noah Davis (1983–2015), and Andra Ursuţa (b. 1979).

The demand for work by young artists is being driven in part by a new generation of collectors, who are interested in acquiring the art of their peers. “The buying pool is much larger than before,” Kevie Yang, head of Phillips Art Advisory, told Artnet News last year. “It used to take years for the artist’s primary prices to go from $50,000 to, say, $200,000. Now it can take a year or even less.”16

According to Art Basel’s midyear art market report released in the summer of 2021, millennial collectors surveyed outspent all other generations, including parting with an average of $20,000 on digital art. In addition, female high-net-worth collectors spent more than double their male peers on average, upping their art investment one-third from 2020, to $410,000.17

Asian collectors are playing a big role in the shift toward the young. Many of the works by international ultra-contemporary artists that broke records at Hong Kong auctions over the past year, including examples by Avery Singer, Joel Mesler (b. 1974), Jonathan Chapline (b. 1987), and Amoako Boafo (b. 1984), were snapped up by Asian collectors aged 45 or younger.18 Asian collectors in general accounted for one-third of all bids by value in Sotheby’s worldwide sales, according to the auction house.19

Some of the artists generating buzz—such as Njideka Akunyili Crosby (b. 1983), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b. 1977), and Emily Mae Smith (b. 1979)—have educational backgrounds similar to those of the generation of art stars that preceded them. (Crosby went to the Yale School of Art, Yiadom-Boakye to Central Saint Martins, and Smith to Columbia University.) Several of the emerging talents out of West Africa—including Amoako Boafo, Serge Attukwei Clottey (b. 1985), and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe (b. 1988)—studied together at the Ghanatta College of Art and Design.20

On the other hand, many artists focused on new media do not have advanced formal training in fine art. The 19-year-old NFT phenomenon Victor Langlois, aka Fewocious, sold his 2021 work Hello, i’m Victor (FEWOCiOUS) and This Is My Life for $2.2 million at Christie’s New York last June—making him the youngest artist to sell at the auction house, as well as the first to crash its site due to high demand.21

Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann, b. 1981) studied chemical engineering before he began making digital art. The $69 million sale of his Everydays: the First 5000 Days at Christie’s in March was followed by the $29 million sale of Human One in November.22 Only after he made a splash at auction did he set out to create his first gallery show, which opened at Jack Hanley Gallery in New York in March.23

Most artists working in the NFT space, however, do not have the kind of market clout to sell directly through auction houses. The vast majority offer their works for sale instead in a steadily increasing number of NFT marketplaces.

Some of the oldest, most traditional museums are exploring new ways to share their art, and new ways to bring in younger audiences.

One of Italy’s most august museums, the Uffizi has slowly begun integrating contemporary art into its programming, mounting shows by such living artists as the British sculptor Antony Gormley, Arte Povera pioneer Giuseppe Penone, and the Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen.24 Meanwhile, the Frick Madison, the Brutalist temporary home of the classic Frick Collection, invited contemporary queer artists, including Jenna Gribbon (b. 1978) and Salman Toor (b. 1983), to hang their work alongside its Old Masters.25

In an effort to reach new audiences—and make money at the same time—some institutions are also experimenting with new fundraising techniques. Four Italian museums, including the Uffizi and the Pinacoteca di Brera, sold digital facsimiles of masterpieces by Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci to raise money for the real works’ conservation. The replicas were shown at Unit Gallery in London on screens that have the same dimensions as the originals and were sold as NFTs in editions of nine priced from £100,000 to £500,000.26

Other museums are opting to fund acquisitions of work by women and artists of color, who are underrepresented in their collections, by deaccessioning pricey paintings by male artists. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, for example, invested more than $50 million from the sale of a Mark Rothko painting into purchasing work by Mickalene Thomas, Barry McGee, and Rebecca Belmore, among others.27

These changes may accelerate as leadership roles continue their generational shift. The majority of museums that have completed their executive searches over the past year—including the Peabody Essex Museum, in Massachusetts, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, in New York, and the Saint Louis Art Museum—have chosen women and BIPOC candidates to lead their organizations.28

To download the full spring 2022 Artnet Intelligence Report, available exclusively to Artnet News Pro members, click here.

Artnet Price Database: From Michelangelo drawings to Warhol paintings, Le Corbusier chairs to Banksy prints, you will find over 14 million color-illustrated art auction records dating back to 1985. Artnet covers more than 1,800 auction houses and 385,000 artists, and every lot is vetted by Artnet’s team of multilingual specialists. Whether you are appraising a collection, researching an artist’s market history, or pricing an artwork for sale, the Price Database will help you determine the value of art.

Disclosures: This material was published on 3.16.2022 and has been prepared for informational purposes only. Charts and graphs were published by ArtNet News in the Artnet Intelligence Report Spring 2022. The information and data in the material has been obtained from sources outside of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley”). Morgan Stanley makes no representations or guarantees as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or data from sources outside of Morgan Stanley.

This material is not investment advice, nor does it constitute a recommendation, offer or advice regarding the purchase and/or sale of any artwork. It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. It is not a recommendation to purchase or sell artwork nor is it to be used to value any artwork. Investors must independently evaluate particular artwork, artwork investments and strategies, and should seek the advice of an appropriate third-party advisor for assistance in that regard as Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC, its affiliates, employees and Morgan Stanley Financial Advisors and Private Wealth Advisors (“Morgan Stanley”) do not provide advice on artwork nor provide tax or legal advice. Tax laws are complex and subject to change. Investors should consult their tax advisor for matters involving taxation and tax planning and their attorney for matters involving trusts and estate planning, charitable giving, philanthropic planning and other legal matters. Morgan Stanley does not assist with buying or selling art in any way and merely provides information to investors interested learning more about the different types of art markets at a high level. Any investor interested in buying or selling art should consult

with their own independent art advisor.

This material may contain forward-looking statements and there can be no guarantee that they will come to pass.

Past performance is not a guarantee or indicative of future results.

Because of their narrow focus, sector investments tend to be more volatile than investments that diversify across many sectors and companies. Diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining financial market.

By providing links to third party websites or online publication(s) or article(s), Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (“Morgan Stanley” or “we”) is not implying an affiliation, sponsorship, endorsement, approval, investigation, verification with the third parties or that any monitoring is being done by Morgan Stanley of any information contained within the articles or websites. Morgan Stanley is not responsible for the information contained on the third party websites or your use of or inability to use such site, nor do we guarantee their accuracy and completeness. The terms, conditions, and privacy policy of any third party website may be different from those applicable to your use of any Morgan Stanley website. The information and data provided by the third party websites or publications are as of the date when they were written and subject to change without notice.

This material may provide the addresses of, or contain hyperlinks to, websites. Except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm has not reviewed the linked site. Equally, except to the extent to which the material refers to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, the firm takes no responsibility for, and makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to, the data and information contained therein. Such address or hyperlink (including addresses or hyperlinks to website material of Morgan Stanley Wealth Management) is provided solely for your convenience and information and the content of the linked site does not in any way form part of this document. Accessing such website or following such link through the material or the website of the firm shall be at your own risk and we shall have no liability arising

out of, or in connection with, any such referenced website. Morgan Stanley Wealth Management is a business of Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC.

© 2022 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 4476524 3/2022