People

Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby Had Her U.S. Museum Debut Abruptly Canceled. Now, She’s Focused on the Future

The abstract painter was one of the earliest self-taught pioneers of digital art in the 1980s.

The abstract painter was one of the earliest self-taught pioneers of digital art in the 1980s.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The international art world was shaken at the start of 2024 when an imminent retrospective dedicated to the Palestinian-American artist and scholar Samia Halaby was abruptly canceled by Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art. The museum cited “safety concerns,” presumably in reference to heightened tensions around Israel’s war in Gaza. The decision was widely condemned, with PEN America branding it “an alarming affront to free expression.”

The exhibition was to be the 87-year-old artist’s first solo show at a U.S. institution, recognizing her achievements not only as a well-established abstract painter but as a bold pioneer in the then-fledgling field of computer art. No matter her medium, Halaby has always been clear about one thing: “I am an abstract painter by strong persuasion. It is the way forward for exploration in the art of picture making.”

Recalling the museum’s shock decision to revoke her retrospective eight months after the fact, in August, Halaby wore a hint of a roguish smile. “I hate to put it this way but it was kind of exciting,” she said.

The show had been three years in the making but Halaby was informed of its cancelation by a two-sentence letter. Soon, the news went global, giving her a platform she put to good use. The artist has long been outspoken in her support of Palestine. “We had the press coming and I could explain things I would never have otherwise explained,” she said.

Samia Halaby, Evening Sky in Amman (1999). Photo courtesy of the artist, New York.

Still, the events weighed heavy. “I wonder if they’re coming to put us in concentration camps like they did the Japanese,” she speculated. “It seems like the State Department is dead set on this horrible massacre.” The most baffling aspect of the museum’s decision? “It just didn’t seem like an abstract painting exhibition was going to cause them much trouble.”

Thankfully, a sister retrospective organized by Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum went ahead as planned over the summer and runs through December 15. Halaby’s work is also included in “Foreigners in Their Homeland,” an unofficial exhibition by Palestine Museum U.S. on view at Palazzo Mora for the duration of the Venice Biennale.

Additionally, this fall, Halaby’s experimental computer-generated artworks star in two significant international group shows: MUDAM Luxembourg’s “Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991,” which closes February 2, 2025, then travels to Kunsthalle Wien in Vienna, and Tate Modern in London’s “Electric Dreams,” from November 28 until June 1, 2025.

The Eskenazi Museum of Art’s decision to cancel Halaby’s show last winter was made all the more galling by the artist’s personal connection to Indiana University. Born in Jerusalem in 1936, Halaby and her family fled the 1948 Palestine war, moving to Beirut before eventually settling in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1951. Over a decade later, in 1963, Halaby completed her MFA in Painting at Indiana University, where she became an associate professor between 1969 and 1972 before transferring to Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Samia Halaby, The City (Al Quds) (1959). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Being Palestinian “informs my very being,” she said recently via a video call from the Tribeca studio she’s kept since 1976. “It’s part of me and my experience and the base of the feelings and responses I have to people.”

That it should be the driving force behind her artistic vision has, however, always struck Halaby as a lazy assumption. After all, her influences extend from the Abstract Expressionists of New York to include early 20th-century Constructivism, Japanese scrolls, and Arabic calligraphy.

“I decided my responsibility was to know everything, not just Western art,” Halaby explained. “It’s all in my work. Some don’t see all the influences because of their ignorance of what I’ve looked at, but that’s okay.”

Her lively, brightly colored paintings are never illustrative. Rather, these impressions emerge intuitively and usually carry poetic names like Flowers for those we love or A night of purple squares and music. These “give the viewer an opportunity to enter the painting,” said Halaby. “People have been frightened away by abstraction and people have also been told they don’t understand. What I want to tell people is trust me, and trust yourself. I think you do understand.”

Samia Halaby, Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza (2024) at “Foreigners in their Homeland,” an unofficial collateral event in Palazzo Mora at the 60th Venice Biennale. Photo courtesy of Palestine Museum U.S.

In order to protect her painting practice from being restricted or unfairly stigmatized by her identity, Halaby has channeled her political sentiments into a much lesser-known, entirely separate strand of her practice. Over her lifetime, she has produced a series of protest posters bearing statements like “stop U.S. aid to Israeli terror” from 1990 and “end the occupation of Palestine now” from 2015. Among her documentary drawings are visual records of her interviews with survivors of the 1956 Kafr Qasim Massacre, which were published as a book in 2016 by the Palestine Museum U.S.

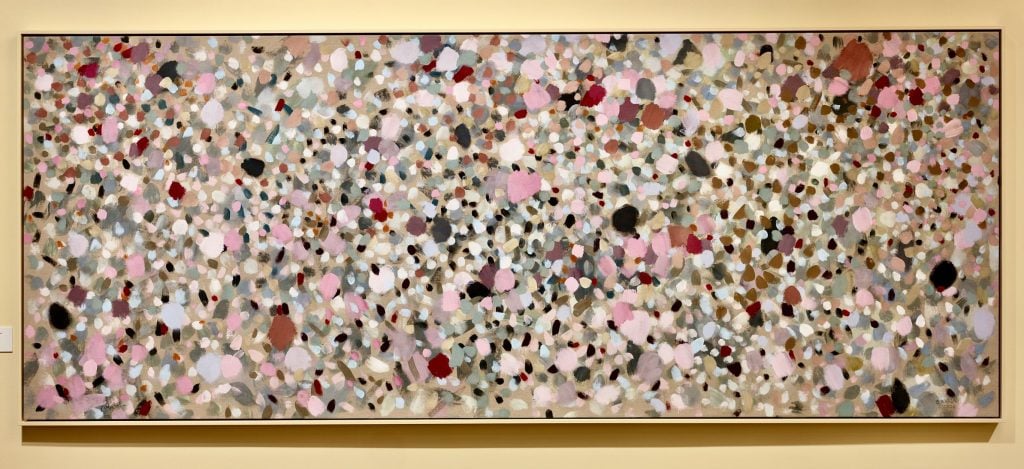

More recently, however, it hasn’t been possible for Halaby to completely separate her fears for her homeland from her painting practice. Massacre of the Innocents in Gaza (2024), a new, somber work currently being exhibited in Venice, was painted while she was hearing an onslaught of devastating news from Gaza. The flecks of pink, red, and orange against a pale grey ground are very much abstract but, like any composition, the work has structure and focal points.

“If you look carefully, there’s a path that is reminiscent of the crowds of marching people that have been evicted from their homes,” Halaby said of one possible interpretation. “At the same time, there is a very deep-seated anger and pain with what’s been happening in Palestine for more than 75 years, since the British came and pretended to have the right to rule us.”

Samia Halaby in her studio. Photo: Lara Atallah.

Another aspect of Halaby’s practice that has rightly received more attention in recent years is her bold investigation into the realm of digital art. “I told myself, if I’m a painter of my time, why am I using a technology that’s 500 years old?” she said. “I wanted to explore.”

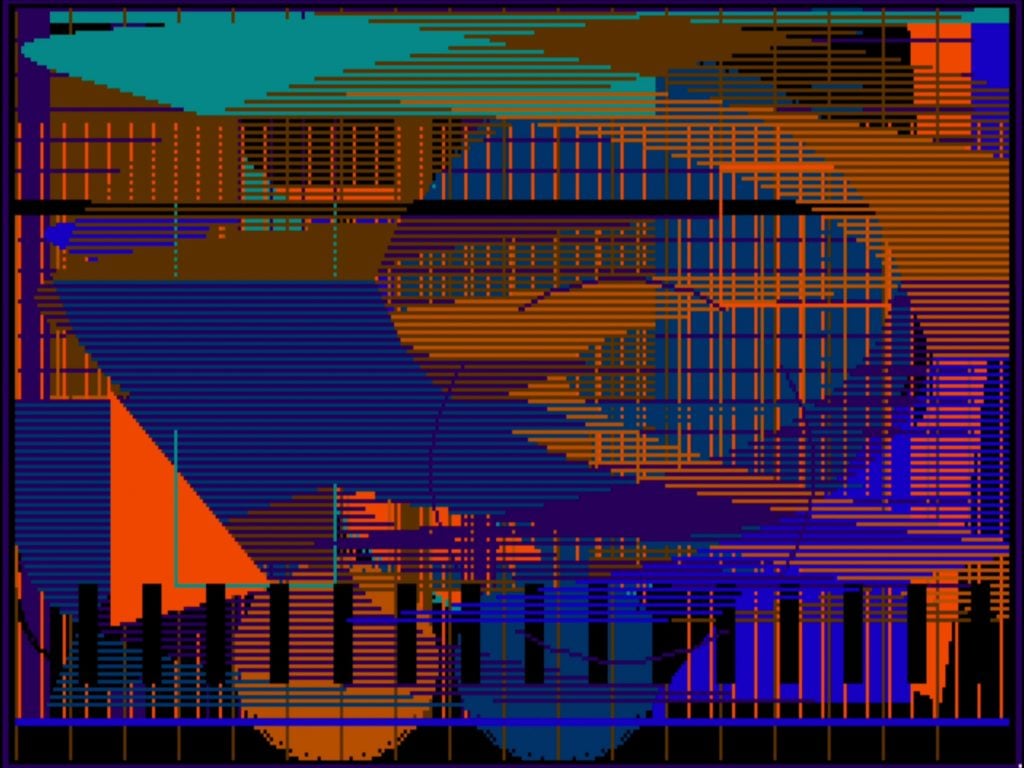

In 1986, Halaby bought an Amiga computer and taught herself to code in the programming language C. She eventually developed software to make animated abstract compositions she dubbed “kinetic paintings,” which excited her colleagues but were not otherwise widely shared.

“I showed them to a friend and we both giggled at them. I still giggle sometimes,” said Halaby. “It was so surprising then to see this computer that is very primitive compared to the ones we use today suddenly show us a whole world of color and shapes that were dinging and zinging about and then close and go back to its dull existence.”

With today’s craze for digital art of all kinds, whether A.I. or A.R., it is hard to imagine just how fringe Halaby’s endeavors were at that time. In 1988, she installed her computer in an uptown gallery where she also screened examples of her digital works on a television. “People looked at them but nobody asked any questions. People also stood around with their backs to them because it was an opening,” she deadpanned. “They do that to the artwork anyway.”

Samia Halaby, Darkstable (1986). Photo courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg.

Attempts to connect with a community of computer scientists outside of the art world were not much more successful. At a SEA Graph conference, attendees were interested in working out how to achieve 3D modeling, which horrified Halaby. “That was the last thing I was interested in. I was saying, ‘Forget it, we did that 400 years ago,'” a reference to the Renaissance artists’ development of perspective in service of an illusionistic painting style.

More interesting to Halaby, an abstract painter at heart, was the task of understanding the computer’s essential nature. Examples of her “kinetic paintings” from the 1980s currently on display in MUDAM Luxembourg’s exhibition “Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991” demonstrate Halaby’s experimentation with a moving picture plane that, unlike the canvas, has a memory. “Things that disappeared can come back,” she explained. Additionally, the screen’s natural luminosity resulted in very bright colors that could change, flashing fast or slow between two tones, “so that shapes can talk to each other.”

Thanks to these discoveries, Halaby considers her digital creations to be a natural continuation of her painting practice. “It opened up new formal attributes that a still image in painting could not have,” she said. “Meanwhile, a still image in an oil painting has subtleties that a digital image does not. Both are fantastic, but the digital is definitely the way of the future.”